A new article on The Conversation, which seems to have gained quite a lot of traction, argues that the modern iconography of witchcraft – namely pointed hats, cauldrons, broomsticks, and cats – can be traced to the commercial practices of, and patriarchal smear campaigns against, the female ale brewers of the late medieval and early modern periods. This is not a new contention, but one that has been circulating online with increasing frequency over the last few years. It’s an appealing thesis that accurately captures the domination of household ale brewing by singlewomen, wives, and widows before the Black Death (one third of women brewed regularly or occasionally in the towns and villages of the early fourteenth century); their increasing marginalisation from the trade as it expanded, capitalised, centralised, and professionalised from the 1350s (accelerated by the arrival and assimilation of a new intoxicant, hopped beer); and the overwhelmingly pejorative cultural construction of female brewers. However, the narrative is also misleading and simplistic, and elides the more subtle and interesting ways in which witchcraft and the manufacture and retail of intoxicants were conceptually intertwined in the medieval and early modern eras.

Leaving aside that the initial decline of female brewing in the late fourteenth century pre-dated the most intensive phase of the witch trials by over 100 years (and the complex causes of the latter), neither pointed hats, cauldrons, broomsticks, nor cats had strong associations with female ale brewers – contemporaneously known as brewsters – in this period, certainly not in England. The claim that brewsters wore tall headgear to make themselves more visible to customers in crowded marketplaces is false; ale soured quickly and was difficult to transport, so surpluses were generally sold not at markets or fairs but directly to neighbours, who collected it in buckets as off-sales or purchased and consumed it on the premises. This bizarre myth seems to have anachronistic origins in this 1672 engraving of ‘Mother Louse’, who apparently kept a well-known alehouse on the outskirts of Oxford. Rather than ‘scream[ing] witchcraft’ (as one online take has it), her ‘dunn hatt’ is a capotain of the kind worn by many men and women between the 1590s and the Civil Wars; like her outmoded ruff, considerable age, and tumbledown premises, it intimated the archaic nature of her product – ‘strong ale’ – at a time when beer, manufactured on an industrial scale by men, had become king.

Likewise, cauldrons seem unlikely to have been inspired by the lead vats, brass pans, and other vessels in which brewsters boiled grain, soaked malt, and drained off wort, not least as these were not specialised tools but everyday utensils found in all medieval and early modern households. Similarly, it seems a reach to discern broomsticks in the ale stakes (usually branches or garlanded poles) that brewsters placed in front of their houses to signify that freshly brewed ale was available for sale, and there is no evidence that they were disproportionately likely to keep pet cats in order to keep mice and other vermin away from their grain.

Instead, as beer historian and archaeologist Christina Wade has demonstrated, stereotypical witch motifs, costumes, and accessories have a wide range of antecedents that have nothing whatsoever to do with the history of brewing. Although the sartorial dimensions of witchcraft await their historian, it seems clear that pointed hats have their origins in (inter alia) classical depictions of the goddess Diana, the antisemitic imagery of the Middle Ages, medieval dunce caps, eighteenth-century chapbooks, nineteenth-century German fairy tales, and the paintings of Francisco Goya. The identification of witches with broomsticks and cats, likewise, has a variety of non-intoxicant-related sources.

That’s not to say there were no imaginative associations between the production of alcohol and witchcraft in late medieval and early modern England; there were, but as Judith Bennett, Marianne Hester, and others have shown, these had to do not with hats, cauldrons, broomsticks, and cats but with sexist tropes that correlated female brewers with other kinds of disorderly and undesirable women. In the fourteenth century, literature, poems, and plays represented brewsters, like witches, as heretical and hypersexualised temptresses who enticed their customers before swindling them with inflated prices and short measures. Media in churches like misericords, bosses, and doom paintings often depicted them gleefully cavorting in the jaws of hell with devils and demons, ale jugs in hand.

By the 1500s, the novel intoxicant beer (originally imported from the Netherlands) was supplanting ale in the nation’s affections; unlike ale, this could not be made domestically, but was produced in technologically advanced industrial settings from which women were largely excluded by credit and custom. Accordingly, earlier representations of brewsters as beguiling and deceitful traders gave way to a second wave of misogynistic portrayals which, as with Mother Louse above, depicted female ale brewers as old-fashioned, shrewish women who crafted antiquated and unwholesome drink. John Skelton’s 1517 poem The Tunning of Elynour Rummyng, apparently inspired by an ale seller in Leatherhead, is the nastiest example of this genre. The eponymous Eleanor is ‘well worne in age’, wears clothes ‘[w]yddered lyke hay’, and ‘breweth noppy ale’, thickened with hen droppings, for ‘foule drabbes’. Her physiognomy, cruelly visualised on the frontispiece of the 1624 edition, is unmistakably witch-like; she has a hooked nose, crooked back, bleary eyes, slack skin, and ‘hobles as a gose’. Like her medieval predecessors ‘the devil and she be sibb’; she also has a ‘lothely lere’ (evil eye), is ‘gressed and annoynted’ like a witch at a sabbat, and it’s implied that one of her unsavoury regulars is a cunning woman.

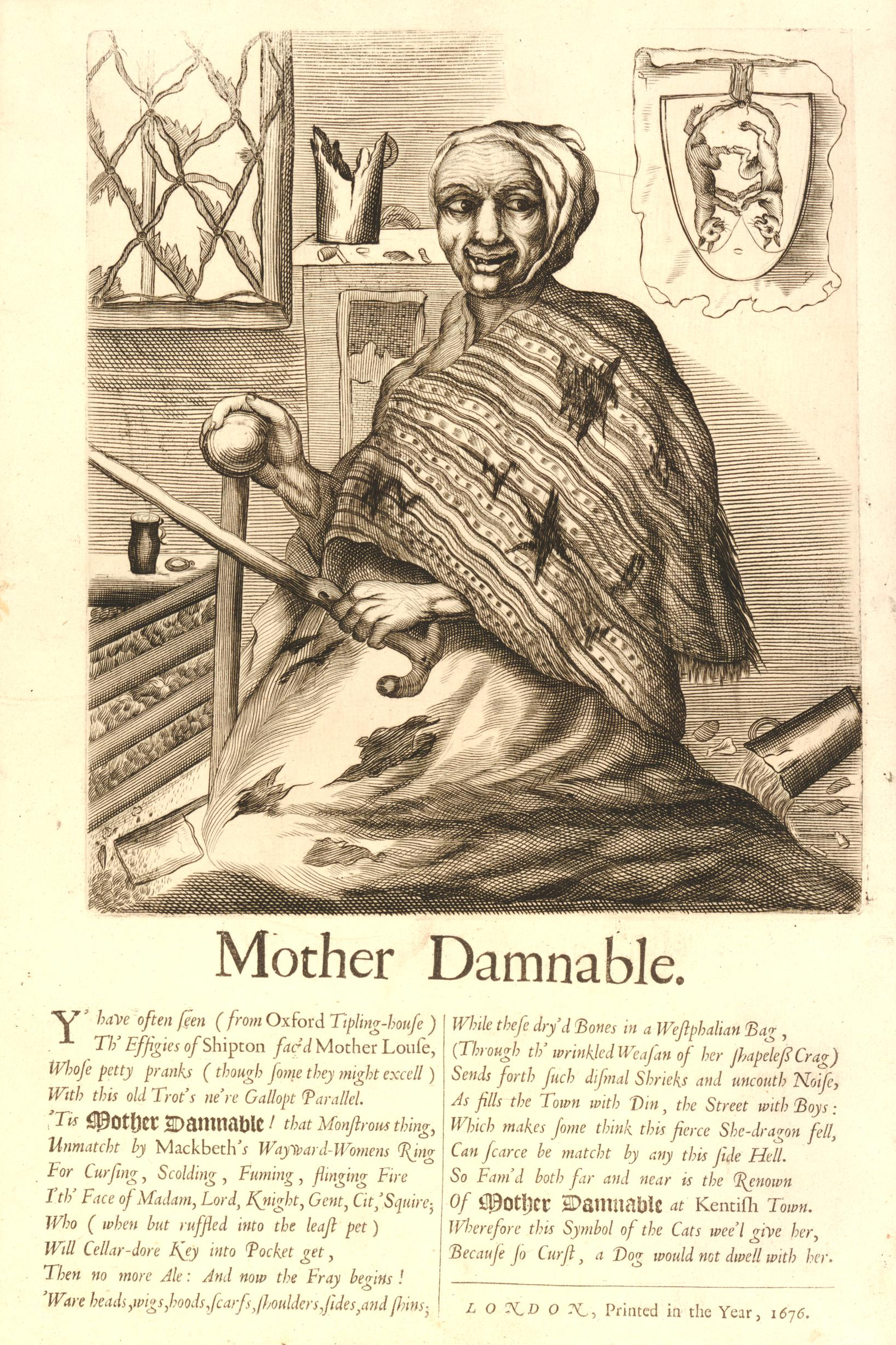

This crone-like 1676 engraving of ‘Mother Damnable’ (also known as Mother Red Cap), apparently based on another real-life folk healer, fortune teller, and alehouse-keeper from Kentish Town, participates in the same visual tradition; the poem introduces her as ‘that Monstrous thing/Unmatcht by Mackbeth’s Wayward-Womens Ring’, and underscores the clues in the image that she runs a violent and disorderly establishment. Likewise, in a telling line from the verse accompanying Mother Louse above, she’s said to possess ‘Orient eyes that nere shed tear’. As Rita Voltmer has recently observed, a common motif in early modern witch trials across Europe was that witches were unable to cry.

Whether these maleficial cultural portrayals rendered female brewers and retailers of ale more vulnerable to accusations of witchcraft is difficult to determine, not least as household brewing was an informal by-employment and witch trial records generally only refer to the occupations of the husbands of defendants. However, there are anecdotal suggestions that this might have been the case; in 1680, for example, alehouse-keeper Joan Cruselander from Aldeburgh in Suffolk sued Mary Lilburne for defamation when the latter called her an ‘old witch’ who ‘hath bewitched me and my family’ and whose ‘house stink[s] of tobacco’.

Further Reading

- J. Bennett, Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300–1600 (Oxford, 1996).

- M. Hester, ‘Patriarchal Reconstruction and Witch Hunting’, in J. Barry, M. Hester, & G. Roberts (eds), Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe: Studies in Culture and Belief (Cambridge, 1996), pp. 288–306.

- T. Vaughan, ‘The Alewife: Changing Images and Bad Brews’, Avista Forum Journal 21 (2012): 34–41.

- R. Voltmer, ‘The Witch in the Courtroom: Torture and the Representation of Emotion’, in L. Kounine & M. Ostling (eds), Emotions in the History of Witchcraft (London, 2017), pp. 97–116.

- C. Wade, ‘Nope, Medieval Alewives Aren’t the Archetype for the Modern Pop Culture Witch’, braciatrix (27 October 2017).

- D. B. Wyrick, ‘‘Withinne that Develes Temple’: An Examination of Skelton’s The Tunnyng of Elynour Rummyng’, The Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 10 (1980): 239–54.