One ear-achingly chilly day in February 2020, forty-odd pupils from secondary schools in Oldenburg and Neu Wulmsdorf, three teachers and I descended on the German Maritime Museum (DSM) in Bremerhaven. Our mission? To explore the museum’s extensive collection of intoxicant-related historical treasures and to brainstorm ideas for an exhibition – researched and curated by students with assistance from staff at the DSM – on the history of tobacco, coffee, tea, chocolate, and sugar in port cities of the early modern period.

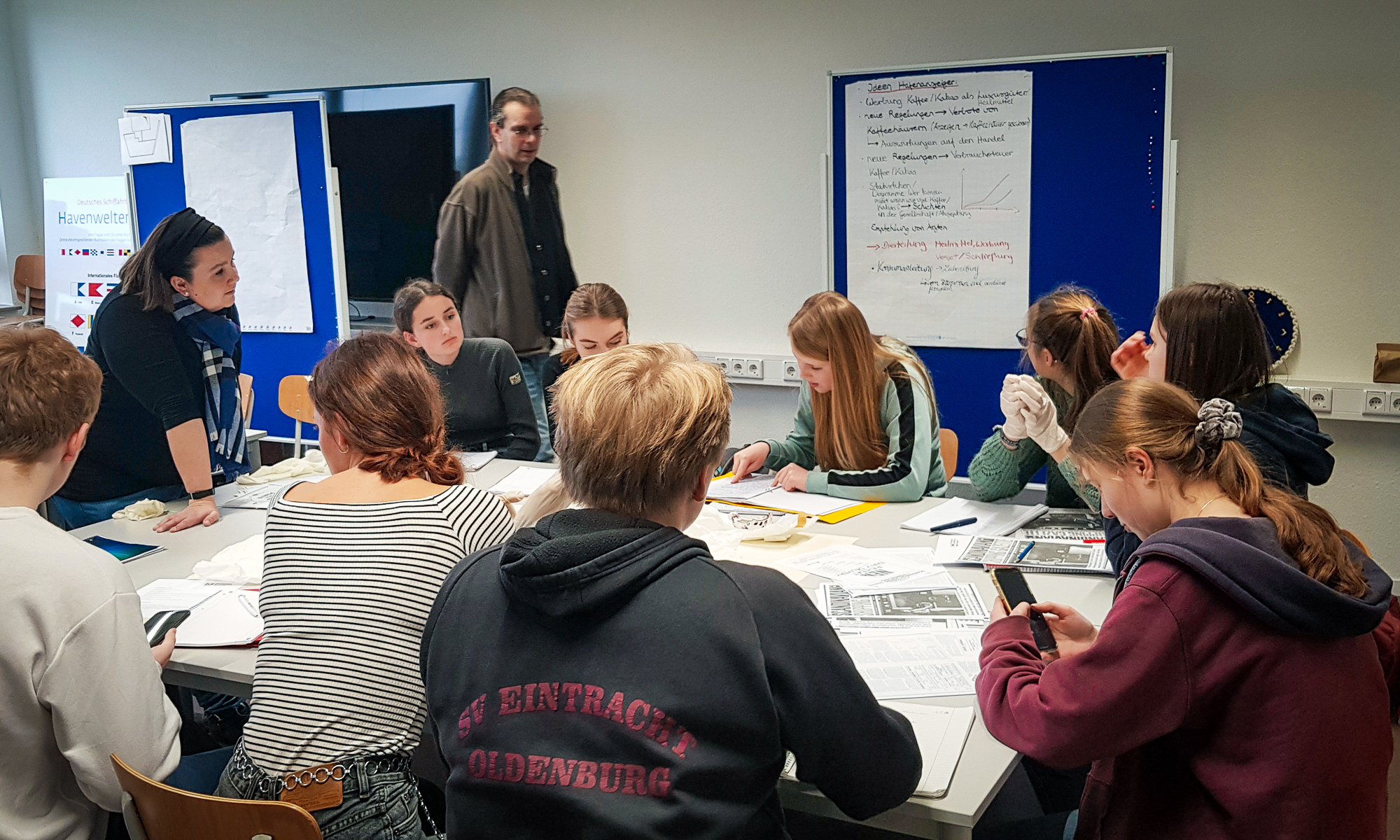

Since late 2019, like all of the national Intoxicating Spaces teams, the Oldenburg group had been meeting regularly with these school groups to introduce them to our research and to how historians work with visual, textual, and material sources to learn about the past. We also helped the groups develop their own historical research projects on intoxicants, which they subsequently presented to fellow school students from Stockholm, Utrecht, and Sheffield at an international virtual schools conference in early 2021. Now we were going to delve into the world of material culture at the DSM.

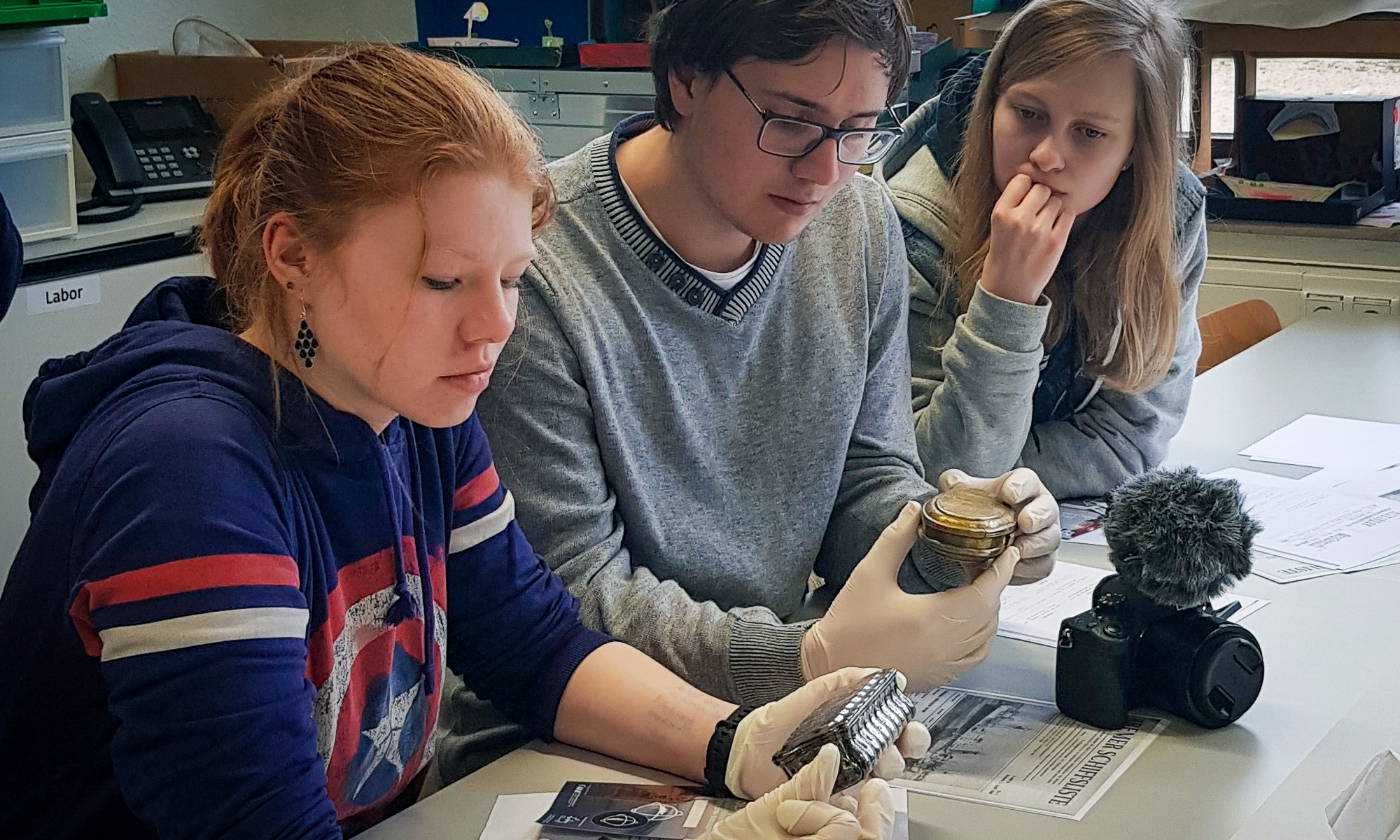

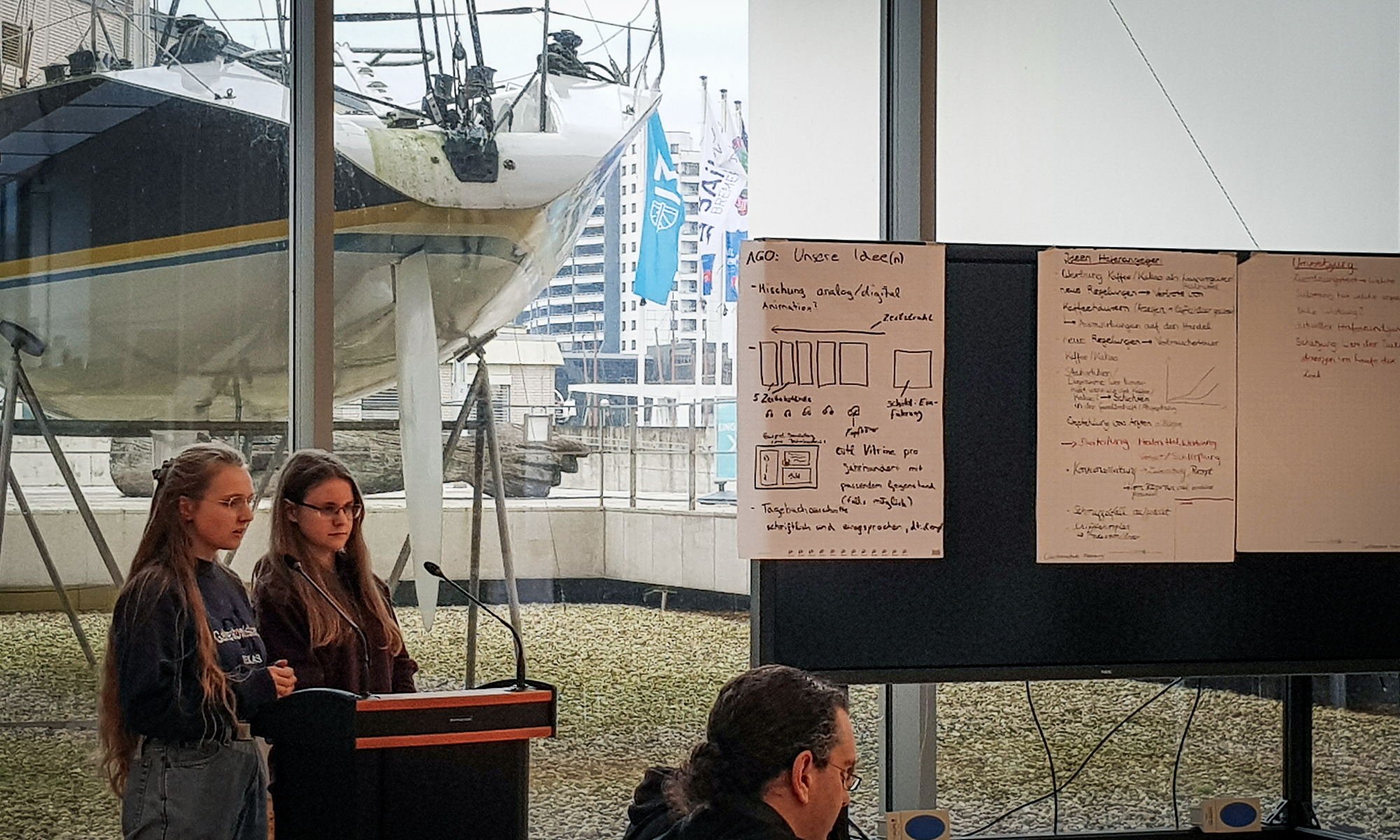

Back in Bremerhaven, with winter coats off and protective gloves on, the school pupils got to work examining a selection of ‘intoxicating’ artefacts from around three-and-a-half centuries of maritime history: snuff and tobacco boxes used by seafarers to store tobacco, some made of metals and elaborately engraved, others plain and of wood; an opium pipe; condiment jars and jugs; coffee pots and the like. Together with their teachers, the school groups discussed how to integrate these objects and their own historical research projects into a museum exhibition that would focus on the role of intoxicants in ports and port cities in the past and the present. The idea was to present the students’ findings in the form of a ‘port gazette’, the traditional medium for communicating important information between ship crews, port workers, and authorities within ports across the globe. Our port gazette exhibition was to be both digital and on-site, consisting of an exhibition ‘wall’ with artefact exhibits at the DSM.

After a thoroughly enjoyable tour of the DSM’s Kogge Halle, so-called after the main exhibit – the impressive remains of a late medieval Hanse freight ship (‘Kogge’) retrieved from 640 years of slick and sediment in the nearby Weser River – we all returned to our respective schools (and university) full of ideas for the upcoming exhibition and looking forward to a series of workshops in which students were to develop and craft their research into an exhibit with the guidance and assistance from the DSM team.

Only weeks later, Germany went into lockdown as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold: pupils were sent home as schools went into emergency (and completely improvised) online teaching, and the museums and universities sent their staff to work from home and shut their doors. It became quickly apparent that there would be no opportunity for physical meetings for months to come, yet we remained optimistic that we could, with a little extemporisation and modification, still deliver both a digital and analogue show. As the school project groups were extracurricular and made up of students from different classes and year levels, this was no mean organisational feat. But thanks to the enthusiasm and hard work of our school groups and their teachers as well as staff at the DSM, we were able to overcome the many logistical and digital obstacles that the COVID-19 pandemic threw our way.