The word ‘intoxicant’ has a central place in this project, as in wider scholarship. But what does the term really mean, and why do historians use it so regularly? Intoxicant is mainly used mainly to describe products which intoxicate – that ‘fuddle or make drunk’, or that artificially alter one’s physiological or neurological state. As Phil Withington and others have argued, whereas alternative words like ‘drugs’ possess strong ideological connotations pertaining to modern society and are more limited in what they evoke (mainly classified substances), intoxicant is a broadly encompassing neutral term, making it useful for describing and investigating a host of present-day consumables in different historical contexts. Usually, as in the Intoxicating Spaces project, scholars who talk about intoxicants refer to a familiar range of narcotics such as alcohols, coffee, opium, tea, and tobacco. Most of these commodities became popular from the early seventeenth century onwards as a consequence of increasing global trade and colonialism.

Getting to the Root of It: Saloop in Early Modern London

After a long night of ‘frolicking’, which included plenty of drinking, the friends George Price and Samuel Plumpton continued their evening with a hot dish purchased from a stall. In many ways these actions seem familiar, almost like grabbing a coffee at the end of a night out. Yet the thick, creamy concoction they stopped for, saloop, is probably unfamiliar. Originally made from powdered orchid roots, the dish was imported from the Ottoman Empire, arrived in the late seventeenth century, and flourished on London’s streets at the turn of the eighteenth century. However, by the late nineteenth century, the drink had faded into obscurity, forgotten from history books, and often discussed as no more than a passing fad. Yet despite its brief lifecycle, saloop provides unique insights into the relationship between the consumption of new exotic goods and the space and routines of the early modern metropolis.

Continue reading “Getting to the Root of It: Saloop in Early Modern London”

Trouble Brewing: Ale, Beer, and Witchcraft

A new article on The Conversation, which seems to have gained quite a lot of traction, argues that the modern iconography of witchcraft – namely pointed hats, cauldrons, broomsticks, and cats – can be traced to the commercial practices of, and patriarchal smear campaigns against, the female ale brewers of the late medieval and early modern periods. This is not a new contention, but one that has been circulating online with increasing frequency over the last few years. It’s an appealing thesis that accurately captures the domination of household ale brewing by singlewomen, wives, and widows before the Black Death (one third of women brewed regularly or occasionally in the towns and villages of the early fourteenth century); their increasing marginalisation from the trade as it expanded, capitalised, centralised, and professionalised from the 1350s (accelerated by the arrival and assimilation of a new intoxicant, hopped beer); and the overwhelmingly pejorative cultural construction of female brewers. However, the narrative is also misleading and simplistic, and elides the more subtle and interesting ways in which witchcraft and the manufacture and retail of intoxicants were conceptually intertwined in the medieval and early modern eras.

Continue reading “Trouble Brewing: Ale, Beer, and Witchcraft”

Workshop Report: Drugs and Drollery

It was an honour for the Wellcome Collection to join Intoxicating Spaces and a group of eminent scholars for an online workshop that took place on 21–22 January 2021 on Modes of Persuasion: Humour and the Promotion and Control of Intoxicants Past and Present. The workshop was originally suggested by Angela McShane while she was head of Research Development at Wellcome Collection. It was a good choice of subject, as the humorous treatment of stimulants and narcotics by promoters and controllers is a significant theme in the Wellcome collections. The main aim of the event was to show how playfulness, levity, satire, and wit have historically been used to inform campaigns and communications around licit and illicit drugs.

Exploring London’s Intoxicating Spaces Through Mudlarking

The River Thames as it flows through London is tidal, meaning twice per day part of the riverbed is exposed for a few hours. This area, known as the Thames foreshore, is a rich archive of (among other things) the remnants of two millennia of the city’s relationship with intoxicants. From tobacco to sugar to opium, the river delivers evidence of how they were imported, refined, sold, and consumed, but it is an archive like no other.

Continue reading “Exploring London’s Intoxicating Spaces Through Mudlarking”

Beer, Wine, and Spirits: Reflections on Intoxicants and Ghosts

This spooky season, while holed up in an isolated farmhouse in deepest North Yorkshire, I’ve been thinking about the connections between intoxicants and ghosts, which haven’t been fully explored in the extensive academic literatures around either topic, but which seem to be many and various.

Continue reading “Beer, Wine, and Spirits: Reflections on Intoxicants and Ghosts”

Plague Time: Intoxicating Spaces and Pestilence in Seventeenth-Century London

One of the most challenging aspects of the lockdown and social distancing measures necessitated by COVID–19 are the restrictions placed on the intoxicating spaces of everyday life. The inability to visit coffee shops, pubs, restaurants, and tea bars is for me and many others one of the most difficult psychological features of the current situation, and the forlorn sight of my favourite Sheffield haunts – many of which have played a small role in the project – standing abandoned like so many urban Mary Celestes is distressing (the UK hospitality sector, like many others, is facing an ‘existential crisis’ as a result of the pandemic). In the context of coronavirus and the new world it’s shaping it seems strange, then, that the growth of coffeehouses in London in the 1660s coincided with the devastating outbreak of bubonic plague that swept the city in 1665. The last and most severe of seven such epidemics that visited the metropolis over the early modern period, and with a fatality rate of around 80%, it ravaged all but four of London’s 130 parishes, killing an estimated 100,000 people in total (roughly a quarter of its population). Like us, early modern Londoners for the most part ate, drank, socialised, and worked outside of their homes; what did the plague and the measures taken to control it mean for their daily experience of the urban environment in general and its intoxicating spaces in particular?

Continue reading “Plague Time: Intoxicating Spaces and Pestilence in Seventeenth-Century London”

Ground Level: Exploring London’s Historical Coffeehouses

One of early modern London’s most common intoxicating spaces was the coffeehouse; a 1739 survey by historian and topographer William Maitland identified 551 institutions in the capital (although the real figure was probably higher), while by the turn of the nineteenth century there were around 2,000 metropolitan establishments, making London the most caffeinated city in the world outside Constantinople. At a loose end before a meeting a couple of weeks ago, I decided to go in search of a handful of better-known City coffeehouses to see what remains of them within the urban landscape.

Continue reading “Ground Level: Exploring London’s Historical Coffeehouses”

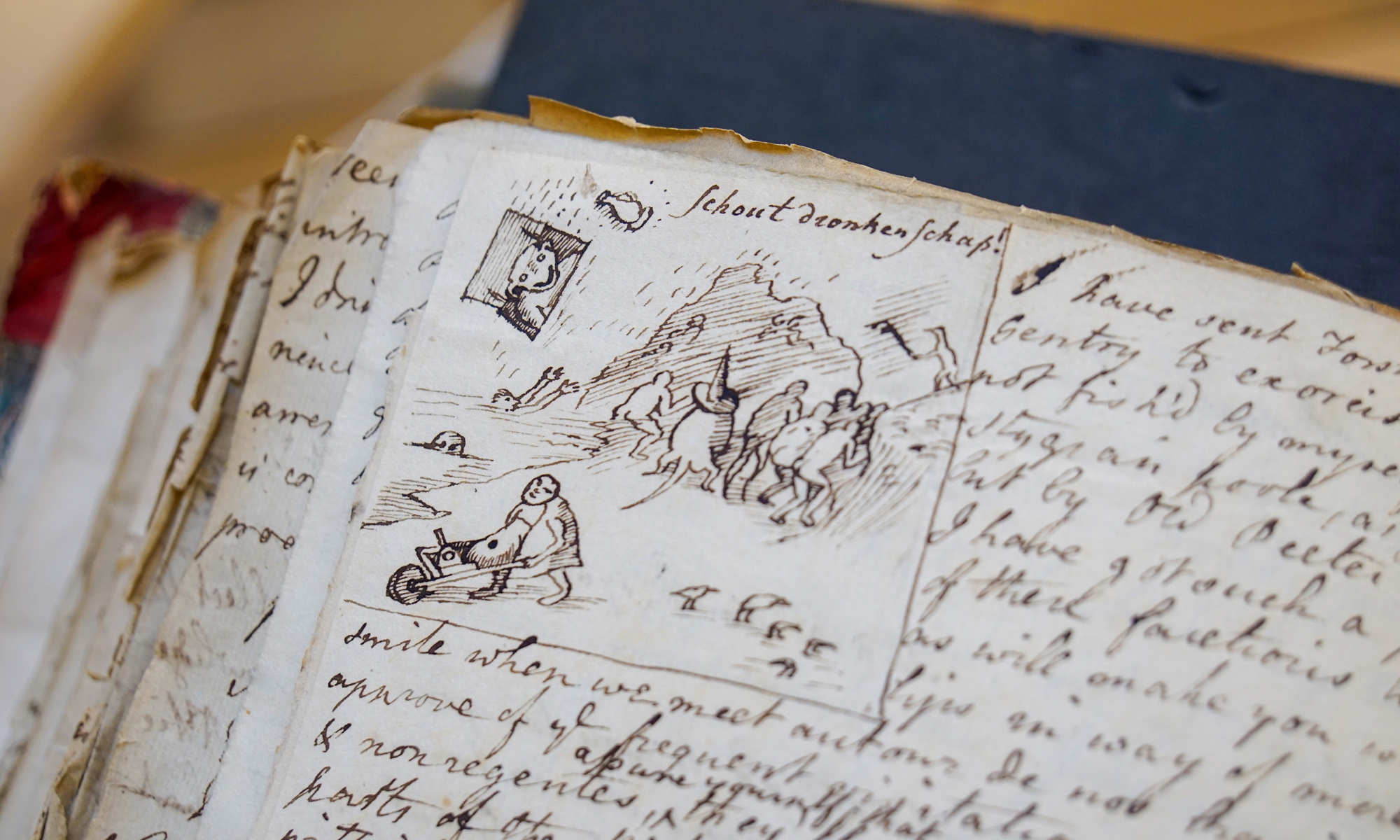

Margin of Terror: Intoxicating Images and Eerie Etchings at the Bodleian Libraries

One of the key sources we’re using to reconstruct the intoxicating spaces of our four case study cities are the so-called ego documents that proliferated across our period: diaries, letters, memoirs, and travel accounts. Some of the UK’s best manuscript holdings of these sources can be found at the Bodleian Libraries in Oxford, so last week saw me on a train to the crisp and autumnal dreaming spires to work through a selection. Ensconced in the wonderful Weston Library, I started with London diaries – including that of a country parson from Oxfordshire who seems to have spent most of his time in the capital purchasing different varieties of tea from Twinings – and, having finished those, turned my attention to their excellent collection of seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century correspondence. This consists of c.50,000 letters, all abstract-searchable within Early Modern Letters Online, an incredibly useful resource created by the Cultures of Knowledge project.