One of the most challenging aspects of the lockdown and social distancing measures necessitated by COVID–19 are the restrictions placed on the intoxicating spaces of everyday life. The inability to visit coffee shops, pubs, restaurants, and tea bars is for me and many others one of the most difficult psychological features of the current situation, and the forlorn sight of my favourite Sheffield haunts – many of which have played a small role in the project – standing abandoned like so many urban Mary Celestes is distressing (the UK hospitality sector, like many others, is facing an ‘existential crisis’ as a result of the pandemic). In the context of coronavirus and the new world it’s shaping it seems strange, then, that the growth of coffeehouses in London in the 1660s coincided with the devastating outbreak of bubonic plague that swept the city in 1665. The last and most severe of seven such epidemics that visited the metropolis over the early modern period, and with a fatality rate of around 80%, it ravaged all but four of London’s 130 parishes, killing an estimated 100,000 people in total (roughly a quarter of its population). Like us, early modern Londoners for the most part ate, drank, socialised, and worked outside of their homes; what did the plague and the measures taken to control it mean for their daily experience of the urban environment in general and its intoxicating spaces in particular?

Just as our cityscapes are newly places of danger – pathogen-laden assault courses to be negotiated with latex gloves, surgical masks, and two-metre exclusion zones – so for the residents of seventeenth-century London the world beyond the front door became treacherous in plague time. The miasma theory of disease prevalent throughout the period associated infection with ‘venomous vapors’, ‘filthy savors’, ‘pestilential miasmata’, or ‘evil and unwholesome aire’, which when inhaled overwhelmed the vital spirits and unbalanced the humours; with their ‘filthy sincks, stincking sewers, channells, gutters, privies, sluttish corners, dunghills, and uncast ditches’, London’s narrow medieval streets had long been seen as a rich source of these deadly aromas. [1] Moreover, while there was no understanding of the biological mechanisms of transmission – specifically, the rat-borne yersinia pestis bacterium that we now know to have been the causative agent of plague – medical writers were aware of the possibility of human-to-human contagion and, in turn, the hazard posed by the capital’s overcrowded tenements and thoroughfares. Writing in response to the 1665 outbreak, William Kemp reported that healthy people could be infected by ‘odious scents’ emanating from the breath, sweat, and sores of sick bodies, while slightly later John Quincy described the afflicted as being surrounded, cloud-like, by what he termed ‘effluvia’ or ‘poisonous atmospheres’. [2] It is in this context that we need to understand clergyman Thomas Doolittle’s blunt caution that ‘[w]hen you walk the streets in this time of plague, you are in danger of death’. [3] Likewise, in a seventeenth-century twist on 2020’s ubiquitous ‘stay home’, the conclusion for one anonymous 1665 pamphleteer was obvious: ‘come abroad [i.e. go outside] as seldome as you can’. [4]

On the basis of these understandings, and in the absence of a cure or vaccine – like COVID-19 for us, plague and related diseases were for our forebears ‘arrows that fly in the dark’ – London’s commentators and authorities advocated and implemented a wide range of spatial containment measures designed to stop the invisible enemy in its tracks. [5] The best-known of these is the forcible quarantining of infected people and other ‘inmates’ within their households for a period of between four and ten weeks; accompanied by the practice of painting a foot-long red cross on the door, this has given us one of the most enduring images of the 1665 outbreak. However, public health efforts went far beyond this. To eradicate toxic miasma, the city’s streets and channels were scoured and scrubbed, pet and stray animals were exterminated, and bonfires fragranced with ‘sweet odours and costly ointments’ such as juniper were set. [6] In terms of social distancing, ‘publique meetings’ and ‘all extraordinary concourses of people… in the streets’ were prohibited; this included fairs and burials, the latter to be ‘done by night’ and without ‘publick assemblies’. [7]

Unsurprisingly given the consensus that ‘promiscuously conversing with one another, do readily propagate the infection’, environments designed for sociability such as public houses, coffeehouses, and other intoxicating spaces were specifically targeted as vectors of contagion. [8] A national proclamation issued by Charles II in 1666 ordered that ‘no more alehouses be licensed than are absolutely necessary in each city’, while citywide plague orders drawn up by the mayor and aldermen the previous year (based closely on previous directives) identified ‘disorderly tipling in taverns, alehouses, coffee-houses and cellars’ as ‘the greatest occasion of dispersing the plague’, and (re)imposed a 9pm curfew. [9] As well as the menace posed by promiscuous conversing, these sites were dangerous in other ways. Physician Gideon Harvey included alehouses (along with chandler’s shops, churchyards, poultries, and shambles) in his roster of ‘close, dirty, stinking, and infected places’, while religiously inclined commentators feared they provoked divine retribution by inciting the sin of drunkenness and gluttony; as one writer explained, in drinking houses ‘the infection might spread and disperse, by reason of the sin, as well as the commerce and throng’. [10] While, unlike today, intoxicating spaces were not subject to mandated and wholesale closure, they do seem to have been avoided by the risk-averse; in February 1666, normally enthusiastic coffeehouse-goer Samuel Pepys reported a trip ‘[w]ith Moore to the coffee-house, the first time I have been there’, and expressed surprise that it was ‘very full, and company it seems hath been there all the plague time’. [11]

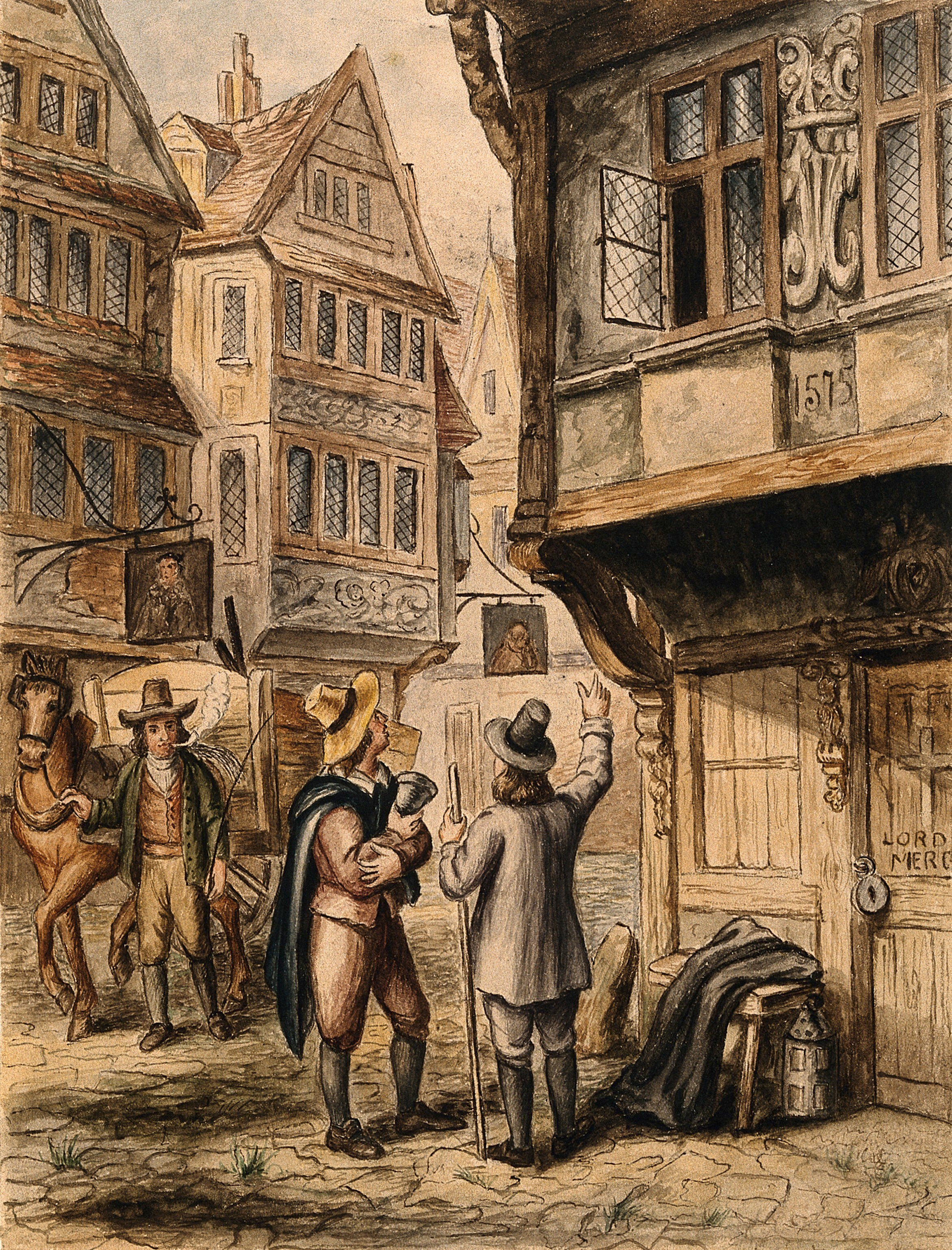

These developments, together with the general reduction of London’s population as wealthier residents abandoned the city for the countryside, wrought dramatic sensory transformations in the experience of urban space. In A Journal of the Plague Year, his fictionalised but accurate 1722 account of the outbreak, Daniel Defoe describes how ‘the face of London was now indeed strangely altered’; two in three shops were shuttered, markets were ‘thinly furnished with provisions’, while the cries of hawkers and the clatter of coaches and wagons were replaced by a ‘profound silence in the streets’. Some deserted thoroughfares, including major paved arteries such as Leadenhall Street, Cornhill, and the Exchange, even started sprouting grass. [12] Frightening visual signifiers of death and disaster in the form of bodies, plague carts, and red crosses on infected houses were everywhere around; Pepys bought some chewing tobacco to settle his nerves after seeing a cluster of the latter in Drury Lane early in the outbreak. Like our city centres today, these and other accounts evoke an uncanny, melancholy place from which all joy had temporarily been sucked. Thomas Vincent lamented that London’s ‘delights are vanished, and pleasant things laid waste’ (including ‘excess of wine and banquettings’ and ‘feasts in halls and curious dishes’), while Defoe observed that ‘everybody began to think of their graves, not of mirth and diversions’. [13] It seems strikingly symbolic that, in a set of 1636 recommendations drafted by the Royal College of Physicians, infected drinking houses are advised to take down their painted pictorial signboards and replace them with ‘some crosse, or other mark set upon thereof to be a token of the sickenesse’. [14]

However, delights, pleasant things, mirth, and diversions of course returned to early modern London, as they will to our city centres; by December 1665 Pepys noted that ‘to our great joy, the town fills apace, and shops begin to be open again’, and the dreadful visitation did little to halt the spread of coffeehouses and other intoxicating spaces, one could say microbe-like, across the urban landscape…

References

[1] S. Bradwell, A watch-man for the pest (London, 1625), p. 4. The air in the countryside, by contrast, was seen as sweet and wholesome, with the exception of damp and foggy environments such as fens, marshes, mines, and moors.

[2] W. Kemp, A brief treatise of the nature, causes, signes, preservation from, and cure of the pestilence (London, 1665). pp. 15–16; J. Quincy, Of the different causes of pestilential diseases, and how they become contagious, in N. Hodges, Loimologia: or, an historical account of the plague in London in 1665 (London, 1720), pp. 272, 276.

[3] T. Doolittle, A spiritual antidote against sinful contagion in dying times a cordial for believers in dying times with a corrosive for wicked men in dying times (London, 1665), p. 161.

[4] Anon., The plagues approved physitian shewing the naturall causes of the infection of the ayre, and of the plague (London, 1665), sig. A4v.

[5] Hodges, Loimologia, p. 44.

[6] Bradwell, A watch-man, p. 11.

[7] Charles II, Rules and orders to be observed by all justices of peace, mayors, bayliffs, and other officers, for prevention of the spreading of the infection of the plague (London, 1666); Corporation of London, Orders conceived and published by the Lord Major and aldermen of the city of London, concerning the infection of the plague (London, 1665), sig. B1r–v.

[8] G. Harvey, A discourse of the plague containing the nature, causes, signs, and presages of the pestilence in general, together with the state of the present contagion (London, 1665), p. 12.

[9] Charles II, Certain necessary directions; Corporation of London, Orders conceived and published, sig. B4r.

[10] Harvey, A discourse of the plague, p. 9; R. Kephale, Medela pestilentiae wherein is contained several theological queries concerning the plague, with approved antidotes, signes and symptoms (London, 1665), p. 8. A similar argument about sin, alehouses, and plague is rehearsed in M. Mead, Solomon’s prescription for the removal of the pestilence, or, The discovery of the plague of our hearts, in order to the healing of that in our flesh (London, 1665), p. 24.

[11] Pepys apparently took social distancing very seriously and is what epidemiologists today would term a ‘super-preventer’; in September 1665 when the outbreak was at its height he commented on ‘the madness of the people of the town, who will (because they are forbid) come in crowds along with the dead corps to see them buried’.

[12] D. Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year (London, 1722), pp. 19, 117–8, 122.

[13] T. Vincent, God’s terrible voice in the city (London, 1667), pp. 69–70; Defoe, Journal, p. 35.

[14] Royal College of Physicians, Certain necessary directions, as well for the cure of the plague as for preuenting the infection (London, 1636), sig. F3v.

Further Reading

- J. Champion, London’s Dreaded Visitation: The Social Geography of the Great Plague of London, 1665 (London, 1995).

- D. Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year (London, 1722).

- A. Hall, ‘Plague in London: A Case Study of the Biological and Social Pressures Exterted by 300 Years of Yersinia Pestis’, MA thesis (University of Oregon, 2008).

- K. L. S. Newman, ‘Shutt Up: Bubonic Plague and Quarantine in Early Modern England’, Journal of Social History 45 (2012): 809–34.

- R. Rideal, 1666: Plague, War, and Hellfire (London, 2016).

- P. Slack, The Impact of Plague in Tudor and Stuart England (London, 1986).