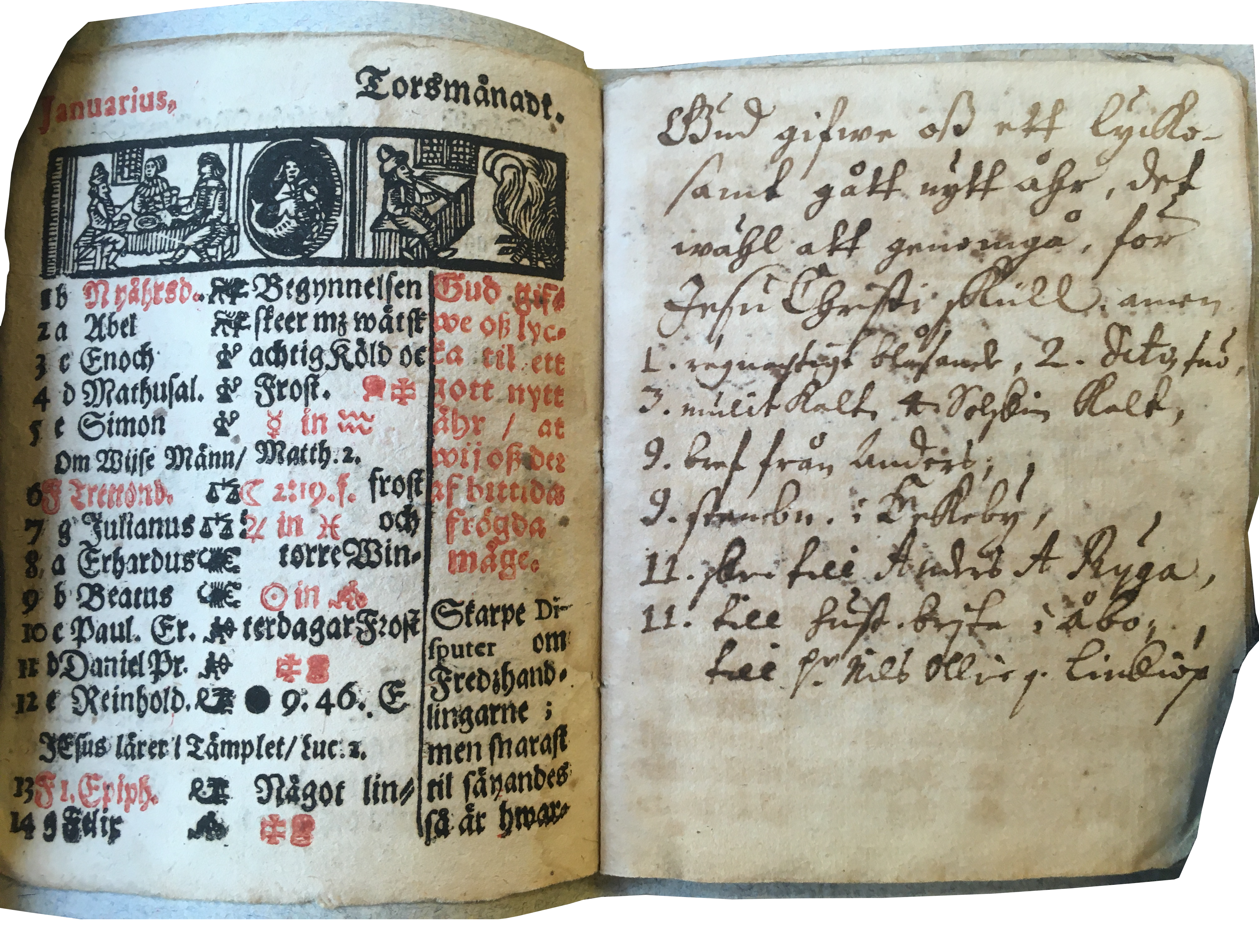

One evening in 1695, the retired non-commissioned officer Lars Ekroth sat down in his home in Stockholm to smoke a pipe. While he was smoking, he received a vision he was sure came from the Holy Spirit. What was revealed to him was that the whole city, including the royal palace, would be destroyed in a great fire, and that the Swedish king Charles XI would die from poisoning. God’s wrath would come upon the country because there was so much sinfulness, ostentation, mistreatment of the poor, and people trying to rise above their station. In particular, it was the sins perpetrated by the Royal Council that had awoken God’s wrath, Ekroth came to understand. When he later related his experience, he said that he was unsure whether he had been awake or asleep during the episode, only that it was when he took his pipe of tobacco that the vision came to him.

Tobacco smoke had many connotations and uses in the early modern era. It was a marker of masculine sociability, unsuitable for female company, but also a means of keeping women of quality away. It formed part of the medicinal arsenal deployed in order to root out dangerous miasmas. But smoke also had spiritual implications that went beyond their possible intoxicating effects. Vapours or fumes were at the edge of the visible, perceptible and tangible, subtle and refined as air and fire. Smoke shared the same aerial and ethereal properties as other difficult to grasp entities like vapours, airs, spirits, vision, perception, dreams, imagination, emotions, and spirits. They all stood at the threshold of the material and the immaterial realms and acted as vectors of cosmic influence. These entities were also equally distributed within human souls, linking physiology and theology with a common vocabulary. Early modern scholars discussed them at length; in some instances they were called pneuma, in others ‘subtle bodies’, ‘subtle matter’, or spiritus. Theoretically this was not always coherent, with their role seen sometimes as medium, at others as an instrument or engine of the soul. What matters here is less the terminology than their function: whether a revelation or a demon, spiritual interaction occurred with entities of rarified, ephemeral substance. Just like tobacco smoke was ‘drunk’, so did spirits and demons sometimes enter the body through the mouth and were drunk. And despite being like vapours, gases, and air, they were still not wholly imperceptible, but moved about like wind so they were registered by the senses and interacted with the vapours that were contained within the body. Being in a dream state or remaining conscious and affected by spiritual visions was difficult to completely ascertain when the entity that affected the body and its sensations was of a similar substance. As if aided by lubricants, spirits might slip into a person, engendering visions, dreams, and subtle sensations.

Ekroth was far from alone in seeing visions and portents in Sweden at the end of the seventeenth century. Indeed, there was a spike in these occurrences around the years 1696 to 1698, during a period that can only be described as disastrous within the realm. The last years of the seventeenth century brought unusual and cold and wet weather, even for the period known as the Little Ice Age. Winters were warm and then there was frost and wet in summer. The result was a serious famine that hit large parts of northern Europe. Within the Swedish realm between 20 and 30 per cent of the population perished in Finland and Estonia as well as the northern parts of Sweden. Thousands of starving people travelled to Stockholm in search of food. However, there hardly was any. The spring of 1697 was so cold that the city was ice-locked until April and so no grain could be imported from across the Baltic. Prophets lamented the state of the realm and its sinful people, their disregard of God’s word and refusal to repent. Ekroth wrote down his predictions and sent them to the King who brushed them off. But the King’s confessor kept the letters, and they came to use later on when it seemed that Ekroth might have been truthful after all.

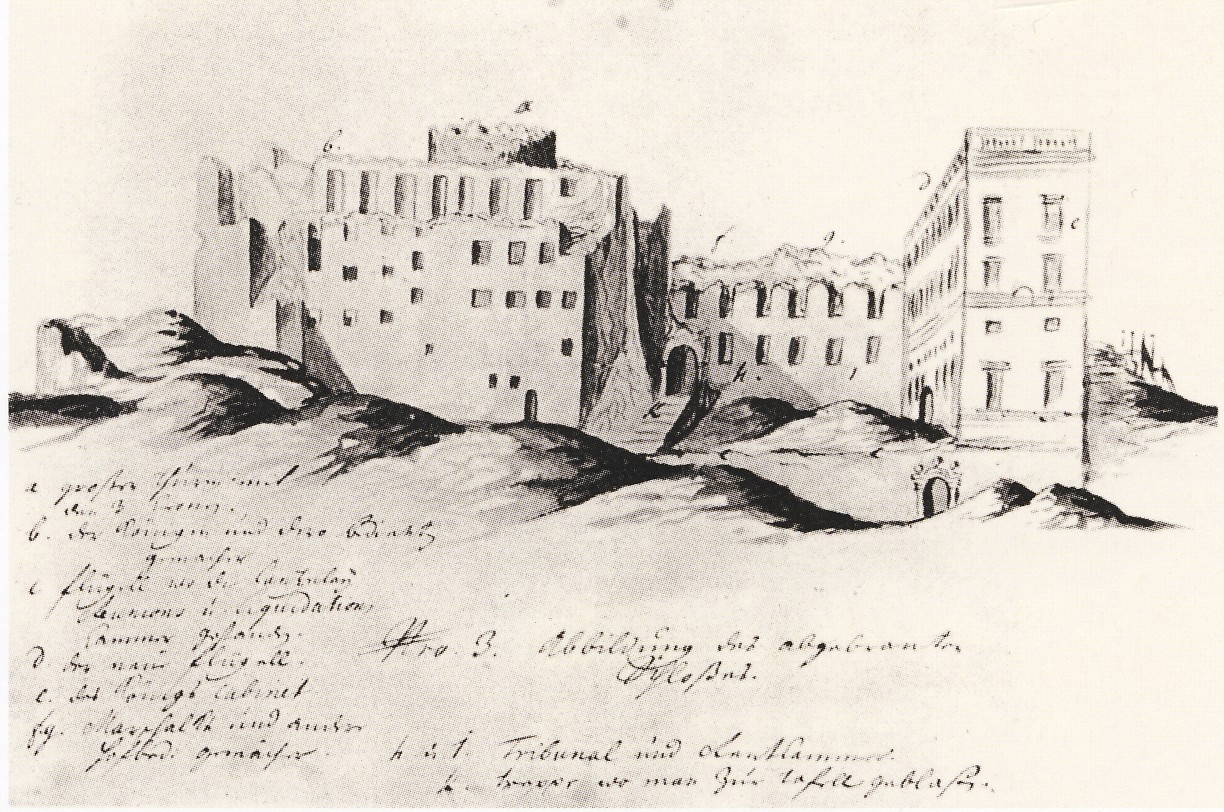

Unlike most other prophets, Ekroth’s smoke-instilled visions proved to be strikingly accurate. In April 1697, Charles XI died at the age of 42, having suffered for years from sharp stomach pains. Rumours immediately emerged that he had been poisoned. Physicians were at pains to determine the cause of his illness, saying it was highly rare and malicious disease that caused a large abscess in the King’s belly. A month after the King died, in early May, the royal palace Tre Kronor was completely destroyed within half an hour in a dramatic blaze. Lars Ekroth had sent warnings only a few days in advance. The Dowager Queen and the fifteen-year-old king Charles XII narrowly managed to escape the fire. The palace held all the state archives and the royal library. Guards and state bureaucrats saved as much as possible, even engaging local rowing women to row the books to safety across from the central island where the palace burned. What was left was a ruin. Symbolically most important was the destruction of the central tower Tre Kronor (three crowns), symbol of the realm, from which the palace got its name. A day after the fire, Ekroth was called to the Royal Council to explain how it was that he had predicted these things. Councillors were divided whether what he had was a divine vision, or whether he in fact had been involved in plotting the fire himself. Certainly, there was no doubt that the many ills that had befallen the realm in such a short space of time were signs of divine wrath. Ekroth was jailed in anticipation of further revelations of hidden knowledge and was permitted to correspond with the new King and the Dowager Queen.

Ironically, intoxicants were involved in the start of the fire, but perhaps not in the way that Lars Ekroth had described. A commission in the following summer determined that the palace fire guards had been running an illegal tavern in the palace attic. Not only were they neglecting their duties, but sold beer and spirits and had built a stove to keep warm. Records do not reveal whether they had been smoking.

Further Reading

- A. Åberg, ‘Slottsbranden 1697’, Karolinska förbundets årsskrift (Stockholm, 1985), pp. 7–19.

- J. Beyer, Lay Prophets in Lutheran Europe c. 1550–1700 (Leiden, 2017).

- C. Göttler and W. Neuber (eds), Spirits Unseen: The Representation of Subtle Bodies in Early Modern European Culture (Leiden, 2008).

- Slottsbranden 1697 (Stockholmskällan).

- J. Spinks and C. Zika (eds), Disaster, Death and the Emotions in the Shadow of the Apocalypse, 1400–1700 (Basingstoke, 2016).

- R. Sugg, The Smoke of the Soul: Medicine, Physiology and Religion in Early Modern England (Basingstoke, 2013).