Private correspondence, in which there has been a recent surge of historiographical interest, is one of the richest sources we have for recovering and reconstructing the day-to-day consumption of new intoxicants by historical actors. The letters of the eighteenth-century novelist and essay writer Isabelle de Charrière, better known in the Netherlands by her maiden name Belle van Zuylen, are a very nice example.

Isabelle de Charrière was born in 1740 in Utrecht to a noble family; her full name was Isabella van Tuyll van Serooskerken. She lived in the Netherlands until her marriage to the Swiss Charles-Emmanuel de Charrière in 1771, dividing her time between a rural castle (where she summered) and a townhouse in Utrecht. From then until her death in 1805 she lived in Colombier near Neuchâtel. As well as her publications (in French), she maintained extensive epistolary connections (also in French) with potential suitors, family members, other writers and intellectuals, nobles fleeing France after the Revolution, and young men and women within her friendship circle whom she mentored.

In many of her letters, of which c.2,600 are extant, we find comments about the physical aspects of life: correspondents advising each other in cases of illness, and mentioning their preferences in eating and drinking. De Charrière’s correspondence is now available and keyword-searchable online. Which new intoxicants are mentioned in the corpus, and how regularly do they appear?

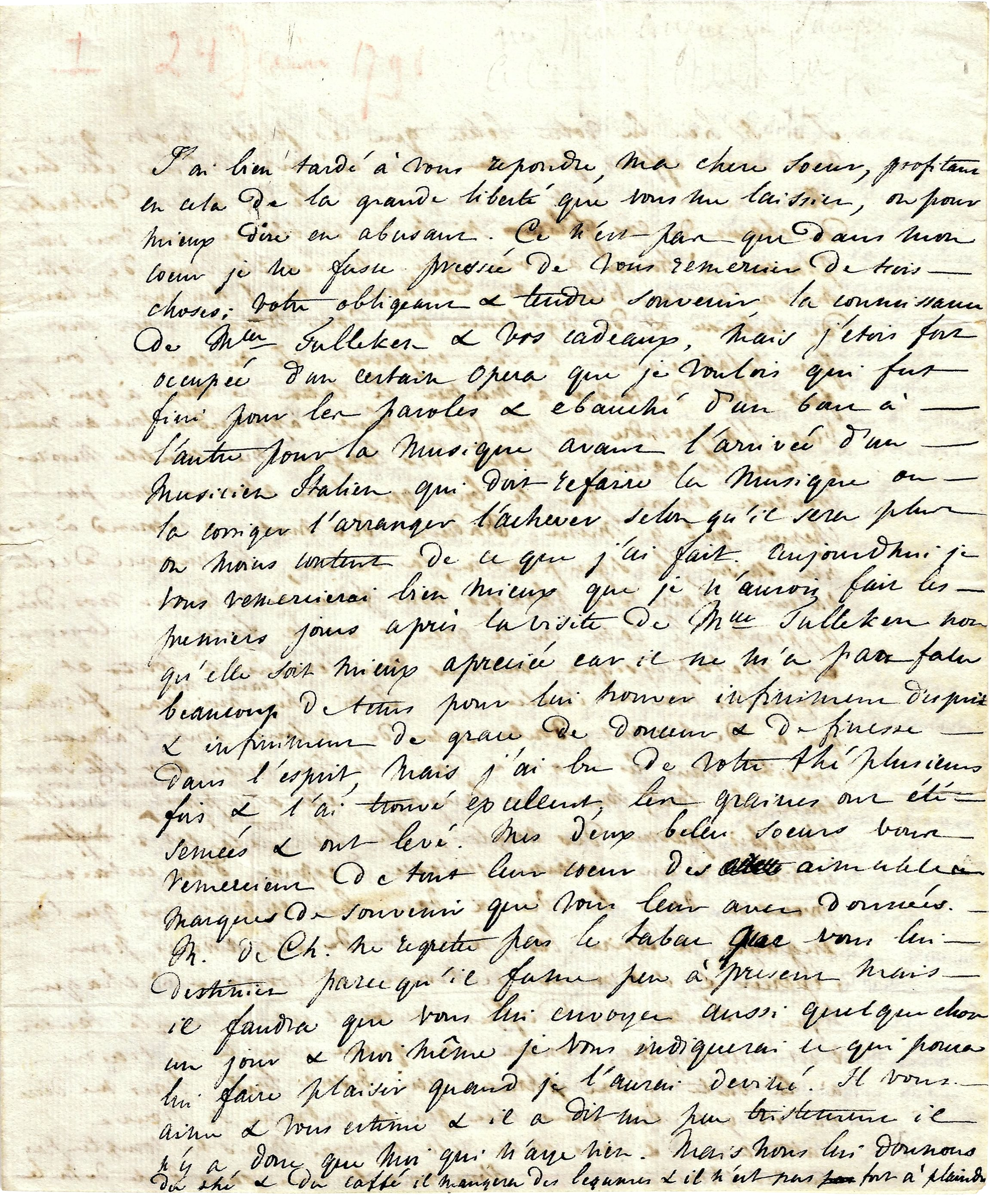

| Letters sent by Isabelle | Letters sent to Isabelle | Totals | |

| Coffee | 25 | 11 | 36 |

| Tea | 40 | 32 | 72 |

| Opium | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Totals | 71 | 49 | 120 |

| Letters sent 1753-1771 | Letters sent 1771-1805 | Totals | |

| Coffee | 11 | 25 | 36 |

| Tea | 14 | 58 | 72 |

| Opium | 3 | 9 | 12 |

| Totals | 28 | 92 | 120 |

Coffee, tea, and opium all feature in her correspondence, appearing in 120 of the letters sent by and to de Charrière. Tea is mentioned the most frequently, appearing 72 times, mainly during the married portion of her life. Coffee receives 36 references, again mainly during her time in Switzerland (with the reported consumption occurring exclusively in private residences rather than in cafés, or coffeehouses). Opium is mentioned 12 times; there are also nine references to chocolate, and scattered mentions of other herbs and medicines.

Time for Tea

Tea is the intoxicant mentioned most frequently within the corpus. It seems to have been served and taken at fixed moments of the day, especially the afternoon, preferably in a context of cosiness and togetherness, and usually among women. In a letter to her favourite brother Ditie, sent from Utrecht in November 1769, de Charrière described being surrounded by three of her friends, Mrs Loten, her cousin Lady Athlone, and her future sister-in-law Miss Fagel: ‘[Y]ou do imagine them, in my room? The first is embroidering, the second reads a book, and the third is serving tea’ (letter 342). Likewise, in May 1800 (by which time she was 60), she invited her young friend Rosette de Bosset de Luze to come over the following Sunday together with Isabelle de Gélieu – if the weather permits – to take tea at six o’clock (letter 2138).

Isabelle sometimes enjoyed tea in the company of male friends, such as the diplomat Chambrier d’Oleyres, to whom she wrote: ‘To sit around a table with some people and have tea, in winter near the fire, is confortable’ (letter 756). Drinking the beverage alone, on the other hand, was not her cup of tea (if I may); in a May 1800 letter to her nephew Willem-René (who had stayed with her in Colombier for several months earlier in the year), she expressed sadness that she would ‘take my tea alone’. After inspecting his former room, she writes – unusually in Dutch – about its horrible cleanness and emptiness: ‘T’was geschikt, geveegt, ledig, en naar’ (letter 2112).

Taking tea at someone else’s residence could become, quite spontaneously, a longer visit; on one occasion she described how Reverend Berthoud came to have tea, stayed for a game of cards, and ended up having ‘souper’, or the evening meal (letter 229). Tea leaves were also given as presents, especially between women, serving as a powerful reminder of the gifter whenever it was consumed by the recipient. In 1791 Isabelle told her Dutch sister-in-law Dorothea that she had ‘drank her tea’ and found it ‘excellent’ (letter 780), while her friend Marie-Anne Morlet expressed similar sentiments about tea van Zuylen had given her (letter 1520).

An Eighteenth-Century Coffee Addict?

Coffee appears to have been taken mainly after dîner, which was taken at lunchtime, not just in the Netherlands and Switzerland, but also when she was staying in England with friends; in April 1767 she wrote to the Swiss colonel David-Louis Constant D’Hermenches that following such a repast ‘after the coffee we played whist, and then everybody went where he needed to go’ (letter 271). Some years before, in 1764, there had been a short period – characterised by stress and tension – during which de Charrière’s drinking of coffee had worried D’Hermenches, on whom she relied extensively for advice. The actual problem was not the coffee, but rather the fact that she was drinking it in the middle of the night. This was because she wrote to him in the evening and at night in order to maintain the secrecy of their correspondence.

These caffeine-fuelled missives to D’Hermenches are full of interruptions. February 1764: ‘This has no sense! I am like falling asleep. Adieu’. The next paragraph continues: ‘It is 11 o’clock now. Thanks to much tea and coffee, I am awake. What I wrote before, should probably be thrown into the fire, yet it is more simple to leave it as it is’ (letter 87). At the end of the same year, she reported that she had been writing – again by candlelight – an important letter, but had to abandon it because ‘I have no brains left, at twelve this night I took coffee, have seen the day coming, and did not put down my pen for a moment. At the end I did not know any more what I was writing about’ (letter 112). D’Hermenches expressed concerns about Isabelle’s nocturnal consumption: ‘This coffee you are constantly writing about is making me desperate – you should rather take opium, or just sleep, and do not write me any letters any more’ (letter 125). She reacted by saying that it is easy for him to suggest these things, as he is a master of his own actions who cannot imagine what addiction (or ‘dépendance’) feels like (letter 127).

Another Reluctant Dutch Opium-Eater

Apparently de Charrière followed D’Hermenches’s advice (or that of a doctor?); some days later she mentioned having quite a calm day, possibly thanks to opium: ‘Are you aware that I am sleeping already? Such calm now, in my mind. But, as perhaps you do not need opium, I say adieu’ (letter 139). However, a month later she reported the drug as unfit for purpose: ‘Each day I was too much awake; walking, speaking, listening, everything was too slow for me, I just needed to continuously run and think. For quite some time I did not eat nor sleep; the opium I have to take is a disastrous refuge’. Seven years later, some weeks after her wedding, she reports being prescribed opium for general aches and pains: ‘Being advised by Hahn I had taken all kinds of medicines, and then took much opium without any positive result. Then I recovered thanks to a small blood-letting, and since three days I am better because of the cinchona powder and musk I am taking five or six times a day. Next to that, each morning I am drinking large quantities of milk of asses’ (letter 397).

There are other intriguing references to opium and its derivatives. In 1793 a doctor advises laudanum as a cure for a goitre (letter 109); D’Hermenches mentions opium humorously in relation to his own euthanasia or mercy-killing (letter 446); Isabelle refers to it as a ‘sleeping pill’ used successfully by the father of a friend (letter 78); the French writer Benjamin Constant refers twice to his ‘friendly opium’ (letters 587, 602); the physician Abraham Liechtenhahn recommends it over spa water for stomach complaints (letter 1621); de Charrière recommends using liquid opium as eye drops (letter 2551); while in 1793 she reported that its consumption causes the same digestive problems as grapes (letter 1135).

In all of these instances, in which opium is mentioned in passing without any special caveats or emphasis, there is no suggestion of shame, surreptitiousness, or scandal. However, we probably need to take into account that these were private communications between close friends, so secrecy was not required.