In Utrecht University Library there is a Dagwyser, or almanac, for the year 1783, which formerly belonged to Joan Gideon Loten (1710–1789), a Dutchman, who had been Governor of Makassar [Sulawesi, Indonesia] (1744–1749) and Ceylon [Sri Lanka] (1752–1757) and who spent most of his career with the Dutch East Indies Company. The Dagwyser is a booklet covered by green parchment, a so-called ‘envelope book’. The entries in the almanac were written in his house in Drift 27, Utrecht, today the location of the university library. The notebook contains short entries nearly every day, mostly in English and Dutch. It contains notations about the people he met in town, who he visited, or who visited him and his wife. A keen ornithologist, he also recorded bird sightings, and noted thoughts and questions to himself.

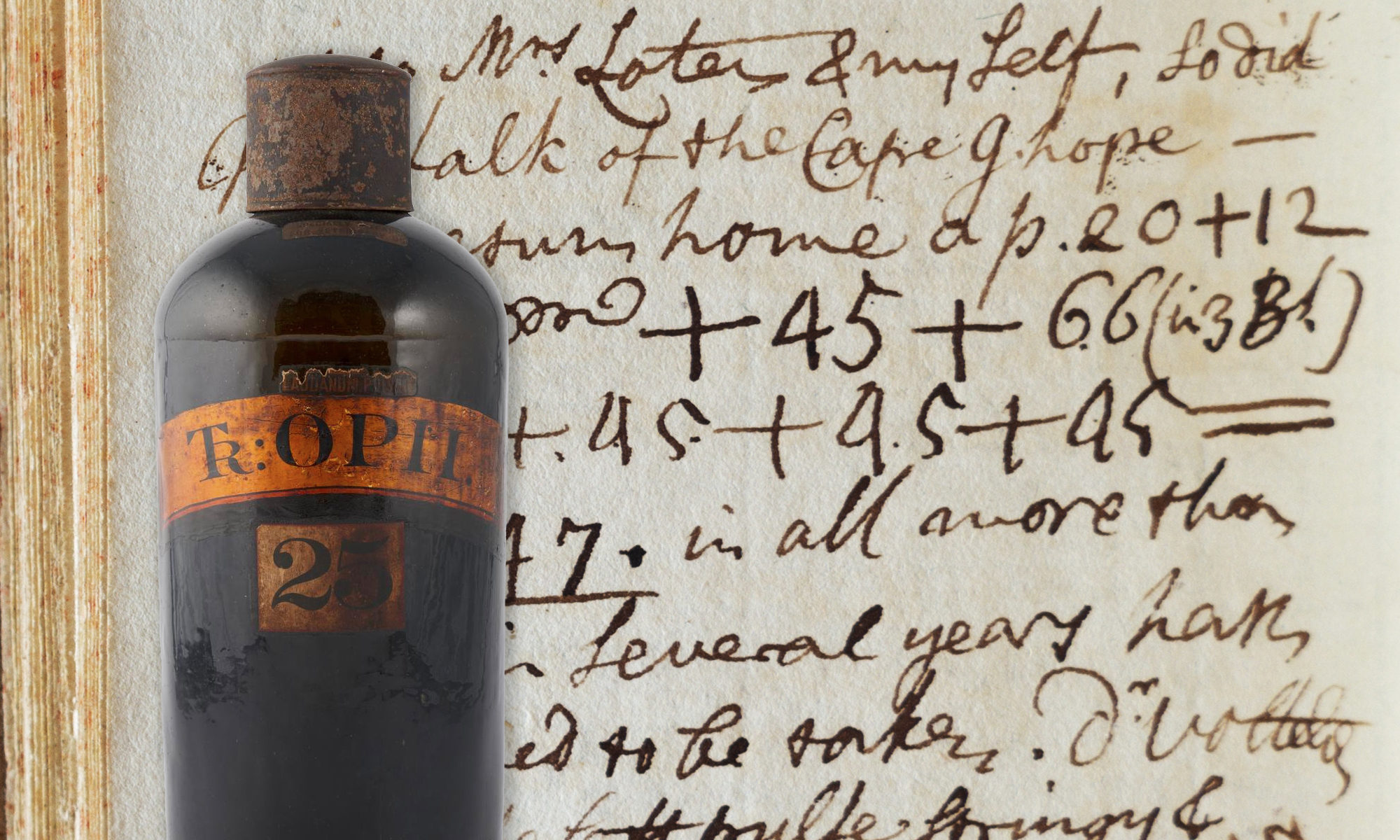

The Dagwyser also contains a detailed daily account of his intake of opium, ingested in the form of drops of liquid laudanum or as grains of opium crystal, that he obtained from the Parisian pharmacist Antoine Baumé (he regularly mentions his correspondence with ‘Fourcy & Baumé & Comp’). Loten compared the opium content of the Baumé grains and the drops of the Sydenham laudanum in his noteboook: ‘14 Baumés of ½ grain I calculate as 168 [drops of laudanum]’. He also reflected upon the side effects of his opium use. On 14 April 1783, for example, he remarked: ‘Strong cramps in right hand and fingers, writing is impossible for about 1½ hours. This has happened many times before, and almost always at the same time. Question: Does the opium here do good or harm?’. In July 1783 he wondered ‘whether long use of opium causes the dropsy in the end?’. Dropsy was ‘an unnatural collection of watery humours in any part of the body’, according to the 1771 edition of the Encyclopaedia Brittanica. Although he was a reluctant user of opium, he concluded in 1775 that he ‘would not reject this medicine, because it is the only ‘friend’ I have found in the large waste bin of the Materia Medica’.

Opium first enters the Loten documents in the early 1770s. In 1772 he consulted Professor Johann David Hahn, who ‘remonstrated against the use of opiates for my indisposition. This is singular because in 1766 when I asked him what to do if such a sudden spasm happened to me, he answered not to hesitate and to take 40 drops of Laudanum ilico, which is a dose that for me, who at that time never used opium in a much larger dose than the 75 yes 100 drops that I am used to now’. He described his situation: ‘Every day I am troubled at least by two attacks of unbearable convulsions in or near the diaphragm. The first at 3 [or] 4 in the morning wakes me up from my first sleep and the second usually comes at 6 [or] 7 in the evening. These spasms only disappear with the use of opium or liquid: laudanum. When I should not use this medication, I should never be able to undress, neither to lie down, nor to enjoy a single moment of sleep, or even to clean my inside, which often became hard when I remained seating in my chair for six even seven days, without removing my clothes, not being able to endure the movements of taking anything off’.

In January 1772 he took a very high dose of opium: ‘[T]he 17th I felt so poorly with spasm after spasm that I took at the same time laudanum in doses of 50, 60, 70, 75 drops (together with tinctura castori three times that dose) within 18 hours 400 drops of that opiate. The last dose stopped the spasms. However, I did not sleep that night… Without lying I can declare that with the exception of opium, I never experienced any evident relief from any medicine from the Materia Medica. More than once, I was warned that it is dangerous for patients to take it carelessly. The careful use is very unprofitable for the doctors and also (because it is a cheap medicine) for the pharmacists. I really regret that I have to use it, which causes that I often postpone the intake, which is further strengthened by my aversion of its smell and taste’. He described his treatment in 1773: ‘[I]n the first place to moderate [the convulsions] by repeated use of opium (put straight by any other antispasmodic drugs). Thus, the opium will not only be a palliative but also probably finally a curative medicine for such a disorder’.

In November 1774 Loten described in detail the sensations he experienced during an asthmatic attack: ‘[I]t is like you can suffocate any moment, and when I am permitted to use an expression that describes it best, it is like the lower part of the omentum is torn open furthermore. The only [relief is] to lean on the couch in your clothes and stay out of bed, or to use in time opium (or its tincture), but this is something you often postpone until the moment to get it or to drop it is gone… [A]s soon as the strong ascending and descending spasmodic contractions are somewhat waning, I experience a very agreeable cool sensation around the præcordium and an elastic feeling in my knees like I could dribble many feet, however nearly at the same moment I feel so spasmodic that I cannot stand up to ring a bell or to open a door. I even do not dare to speak or to move my body on my chair; and even a woman dressed in a rustling silken robe, a chatting or whistling parrot or a dandyish greenhorn are able to set the miraculous mechanism of the diaphragm in motion’. In 1775 in one of his genealogical notebooks he formulated his opinion of the opium drug: ‘As to the taking of opium here there are but two articles of choice: to take this pernicious drug in great destroying quantities, merely to exist miserably, or, to die in the most horrid fits by not taking it. Thus, the case requires no hesitation, and of the two great evils the least to be chosen’.

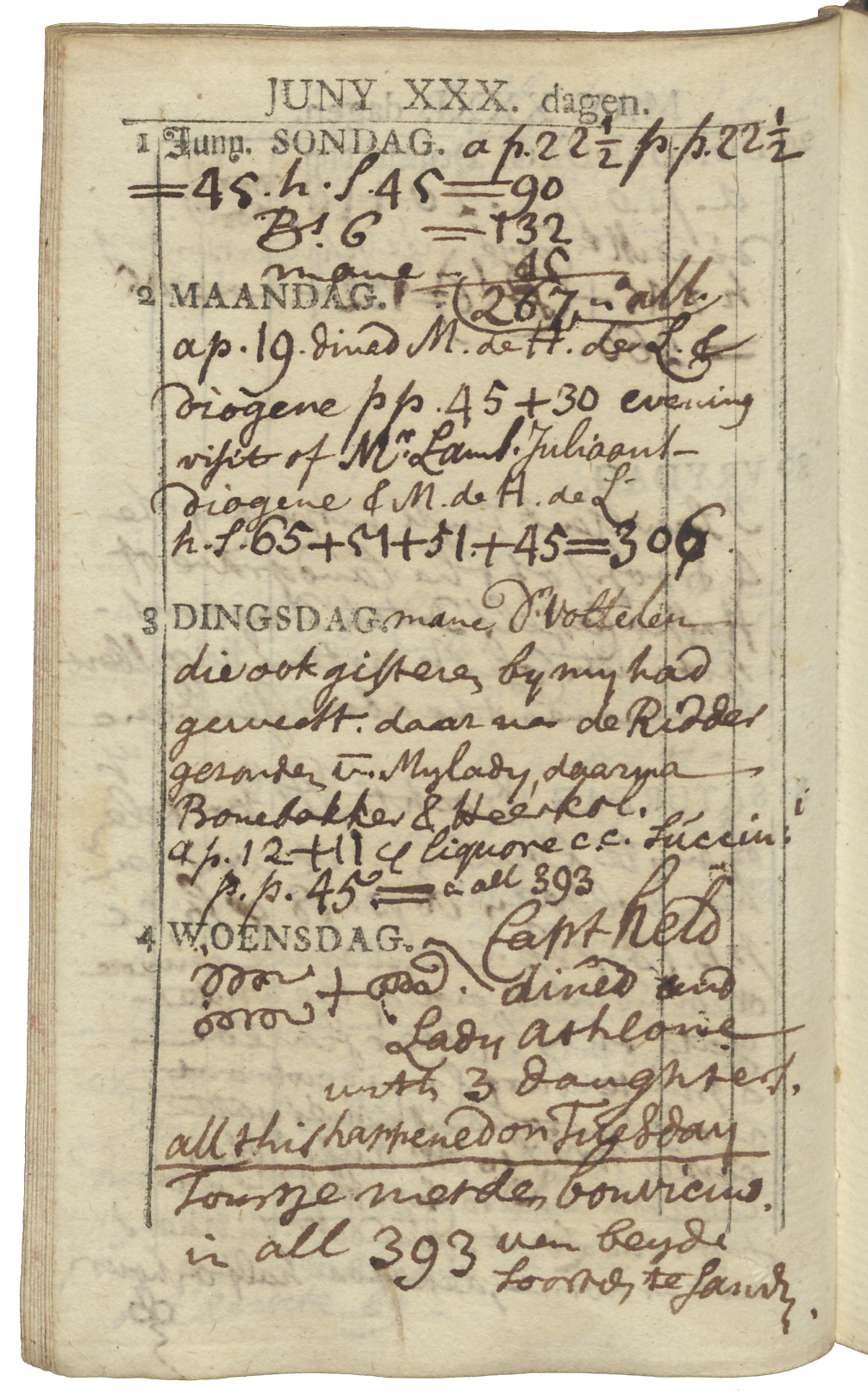

In the 1783 notebook Loten’s entries about his health are usually very short, and no serious complaints are mentioned. In April 1783: ‘Bad cold, barely breathing with a sore chest and wheezing. The pain in the chest unbearable. No help, but four Baumé’s grain pills and some liquid laudanum Sydenhami between them. An easy night followed and healed the ailment’. However, he also wrote about his ‘tossing and turning in bed’. On 31 May 1783 Loten recorded that he had taken 347 drops of laudanum: ‘In all more than lately in several years hath happened to be taken’. The next day he asked his doctor to come, who ‘found the left pulse stringy and harsh’. Apparently, nothing was amiss. In August 1783 he remarked: ‘The entrails, or heart down as with a pump, but not lasting, more like an infinite part of a second’, which sounds less alarming than the descriptions of his complaints ten years before. In 1783 Loten used opiates every day and specified the number of drops and Baumé grains in the morning, afternoon, evening, and night. He used it to soften his asthma attacks, but also to prevent asthmatic convulsions. If the daily dose in 1783 is compared with that in the period 1774 to 1777, it appears that his intake of the drug had doubled. However, the Dagwyser shows that Loten was active almost every day, making visits, receiving visitors, and taking carriage rides around Utrecht, perhaps indicating that opium was effective in suppressing the worst symptoms of his asthma.

Further Reading

A. J. P. Raat, The Life of Governor Joan Gideon Loten (1710–1789): A Personal History of a Dutch Virtuoso (Hilversum, 2010).