The River Thames as it flows through London is tidal, meaning twice per day part of the riverbed is exposed for a few hours. This area, known as the Thames foreshore, is a rich archive of (among other things) the remnants of two millennia of the city’s relationship with intoxicants. From tobacco to sugar to opium, the river delivers evidence of how they were imported, refined, sold, and consumed, but it is an archive like no other.

The Thames’ currents constantly erode the foreshore’s surface, freeing objects and sorting them, not by period or purpose, but by weight and shape. Romano-British wine flagon necks, late medieval Rhenish ale krug fragments, plastic McDonald’s straws, three centuries of clay tobacco pipes, nitrous oxide canisters from last night’s party, Georgian sugar refining waste, and shards of Victorian opium-laced nostrum bottles, all lie chaotically strewn together along with a multitude of other debris. London’s mudlarks – the name given to the amateur archaeologists who search the foreshore – embrace this chaos, the foreshore providing them with the chance to find connections and patterns across a huge range of materials. Here are just a few of the intoxicating finds made by myself and some of my fellow mudlarks…

Tobacco

The English, followed by the Dutch, were the first Europeans to adopt the clay pipe as their preferred means by which to inhale tobacco smoke. While visiting London in 1598, German lawyer Paul Hentzner observed ‘the English are constantly smoking tobacco and in this manner: they have pipes on purpose, made of clay’. [1]

The precise origins of the clay tobacco pipe however, are less clear. Claims have been made that the clay pipe was a direct invention of Native Americans which was then replicated in England, that it was derivative of indigenous pipes made from other material, such as a walnut shell and a straw, and that it evolved from devices already used in England for insufflation for medical purposes. [2] This debate notwithstanding, the first English purpose-made clay tobacco pipes seem to have emerged in the 1580s as the smoking of tobacco was popularised by the returning Roanoke colonists, becoming a fashionable badge of adventure and of support for English colonial ambitions.

These earliest clay pipes feature the smallest bowl size of those found on the foreshore, reflective of the high price of tobacco prior to England securing its own direct supply. [3] This began to change when John Roalfe successfully cultivated tobacco crop in the colony of Virginia and shipped it to London in 1616. By the 1620s, a pipe full could be had for less than a farthing and pipe bowl sizes increased as tobacco became more affordable and consumption spread to all tiers of society. Critic of smoking Barnaby Rich duly complained that a Londoner might now have ‘his pot of ale, his pipe of tobacco and his pocksy whore and all for his 3d’. [4] Clay tobacco pipes were also manufactured in the American colonies, examples of which are occasionally found on the foreshore, probably carried to London by mariners returning from the Americas (see this example of a ‘Chesapeake’ pipe, manufactured in Virginia, found by mudlarker Anna Borzello). These have been read as creolized objects – a product of the unique interactions between enslaved Africans, Native Americans, and Europeans in Virginia.

During the mid-eighteenth century, amid a wave of self-conscious patriotism, more elaborately decorated pipes were being manufactured in London featuring the arms of the ruling House of Hanover. These have been associated with Tom King’s Coffee House in Covent Garden Piazza. [5] Open from when the taverns shut until dawn, Tom King’s was less focused on serving coffee and more on providing a place for drunken patrons to gamble and pick up prostitutes. As such, Tom’s disrupts the portrayal of the coffee shop as an alcohol-free space for conversation, more serious than that of the alehouse.

Sugar

The seventeenth century saw a chronic shortage of official small change in circulation, prompting tradesmen to privately issue tokens redeemable at their business. In 1650, a Mr T. Dry of Wapping – a neighbourhood on the north bank of the Thames inhabited by a community of maritime tradesmen – issued a halfpenny token bearing a shop sign consisting of three loaves of sugar, suggesting he was a grocer, or at least worked nearby one.

If Mr Dry was indeed in the grocery trade, his sugar may well have originated in the plantations of Portuguese Brazil, which supplied most of England’s sugar in the first half of the seventeenth century. As England established its Caribbean colonies and expanded their labour force by shifting to the use of enslaved Africans, sugar from the West Indies became the norm. Evidence of the West African trade, of which enslaved people were a fundamental component, can be found on the foreshore in the form of drawn glass ‘trade’ beads – one of the many European commodities exchanged.

It was long thought such beads were not manufactured in England, and were instead sourced from Venice, Amsterdam, and other European production centres. An excavation by the Museum of London Archaeology on the bank of the Thames in Hammersmith, however, revealed the remains of two seventeenth-century glass furnaces and bead manufacturing waste. The furnaces were established by Sir Nicholas Crispe (1598–1666), owner of a controlling interest in the Company of Adventurers of London which traded in ivory, hides, redwood, gold, and enslaved Africans on the Guinea coast. [6] Beads of the types manufactured by Crispe are frequently found on the foreshore, although establishing their exact provenance remains challenging.

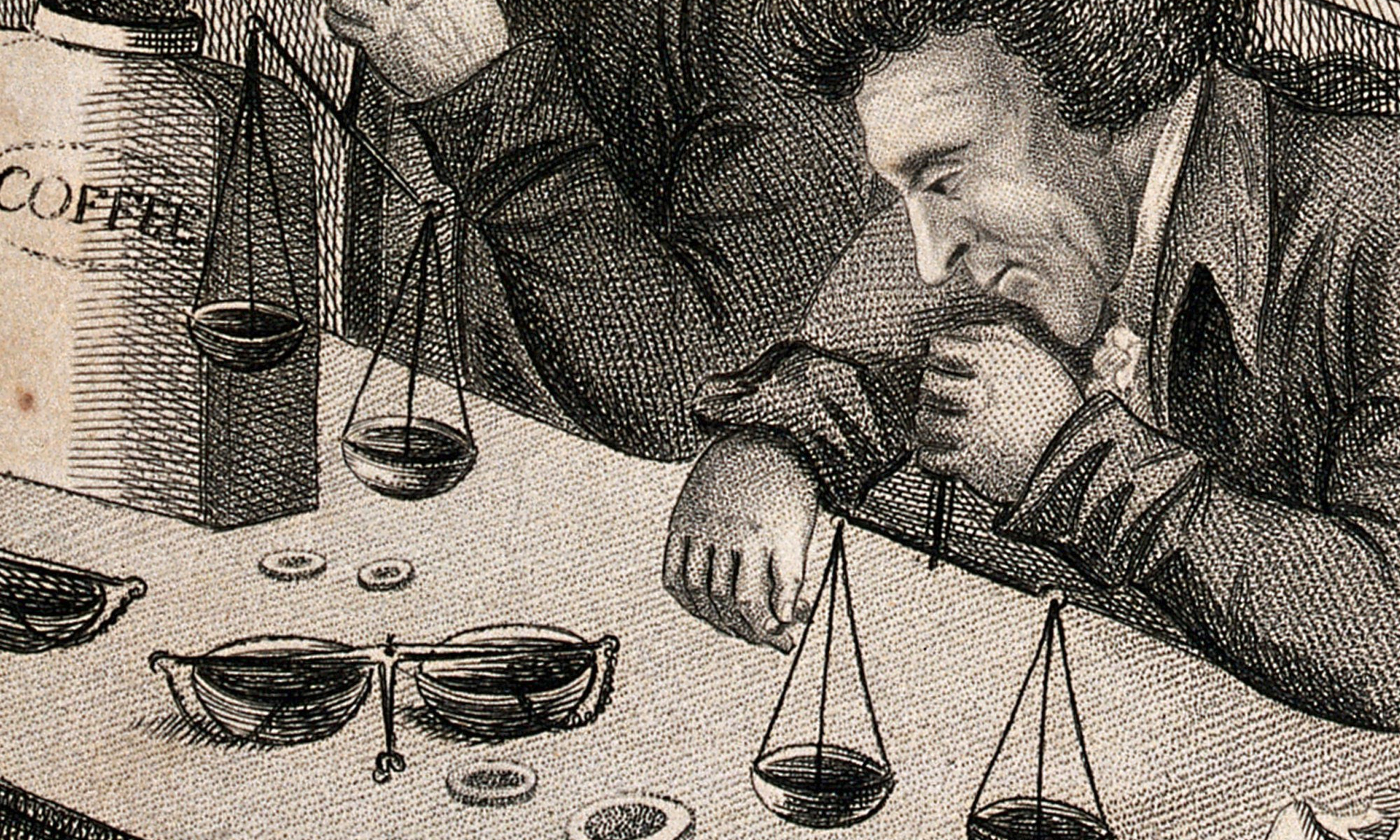

By the 1680s, the English Caribbean was producing as much sugar as Portuguese Brazil. Unlike Brazilian planters, who produced large quantities of white refined sugar, 90% of the sugar shipped by English planters, encouraged by the state, was semi-processed muscovadoes. [7] This led to an expansion of sugar refining in London, with eighty sugarhouses being reported in the capital by 1750. Evidence of this trade can be found on the Thames foreshore in the form of a huge number of fragments of ceramic sugar moulds. After being treated and boiled, sugar was poured into earthenware moulds and left to mature for several months. When ready, the mould was turned upside down and the sugar loaf removed, trimmed, and distributed for sale by grocers across the country. When consumed within the eighteenth-century household or coffeehouse, a chunk of sugar was ‘nipped’ from a loaf using a metal plier-like object and then broken up in a drink of tea, coffee, or chocolate with a glass sugar crusher.

Opium

Eighteenth-century medicine bottles occasionally emerge intact from the foreshore, protected by the cushioning effects of the Thames mud. Whether based on the officially sanctioned Phamacopoeia Londinensis, or an apothecary’s nostrum, opium was a common ingredient in the medicines they contained. Alongside supplying the city itself, London’s rapidly expanding, hot, busy, and sometimes dangerous medical laboratories supported colonial labour regimes. [8] In his widely-read piece of 1802, An essay on the more common West-India diseases and the remedies which that country itself produces, Scottish doctor James Grainger detailed how plantation owners could keep the bodies of enslaved Africans fit for work. Grainger recommended every plantation owner should have 25 medicines imported annually from England, including opium, rhubarb, crude mercury, cloves, and alum.

References

[1] F. Fairholt, Tobacco: Its History and Associations (London, 1876).

[2] R. Rowley, ‘How England Learned to Smoke: The Introduction, Spread, and Establishment of Tobacco Pipe Smoking in England Before 1640’, unpublished PhD thesis (University of York, 2003), p. 57.

[3] A. Oswald, ‘The Evolution and Chronology of English Clay Tobacco Pipes’, Archaeological Newsletter 7 (1961): 69.

[4] B. Rich, The Irish hubbub, or, The English hue and crie briefly pursuing the base conditions, and most notorious offences of the vile, vaine, and wicked age, no lesse smarting then tickling (London, 1618), p. 44.

[5] D. Atkinson & O. Oswald, ‘The Dating and Typology of Clay Pipes Bearing the Royal Arms’, The Archaeology of the Clay Tobacco Pipe, BAR Series 78 (1980): 364.

[6] K. Karklins et al, ‘A 17th-Century Glass Bead Factory at Hammersmith Embankment, London, England’, BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers 27 (2015): 16.

[7] N. Zahedieh, The Capital and the Colonies: London and the Atlantic Economy 1660–1700 (Cambridge, 2010), pp. 214, 217.

[8] Z. Dorner, Merchants of Medicines: The Commerce and Coercion of Health in Britain’s Long Eighteenth Century (London, 2020), p. 137.

Further Reading

- D. Atkinson & O. Oswald, ‘The Dating and Typology of Clay Pipes Bearing the Royal Arms’, The Archaeology of the Clay Tobacco Pipe, BAR Series 78 (1980).

- ‘Chesapeake Pipes’, University of Virginia Library.

- Z. Dorner, Merchants of Medicines: The Commerce and Coercion of Health in Britain’s Long Eighteenth Century (London, 2020).

- F. Fairholt, Tobacco: Its History and Associations (London, 1876).

- J. Grainger, An essay on the more common West-India diseases and the remedies which that country itself produces (London, 1802).

- K. Karklins et al, ‘A 17th-Century Glass Bead Factory at Hammersmith Embankment, London, England’, BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers 27 (2015).

- A. Oswald, ‘The Evolution and Chronology of English Clay Tobacco Pipes’, Archaeological Newsletter 7 (1961).

- B. Rich, The Irish hubbub, or, The English hue and crie briefly pursuing the base conditions, and most notorious offences of the vile, vaine, and wicked age, no lesse smarting then tickling (London, 1618).

- R. Rowley, ‘How England Learned to Smoke: The Introduction, Spread, and Establishment of Tobacco Pipe Smoking in England Before 1640’, unpublished PhD thesis (University of York, 2003).

- N. Zahedieh, The Capital and the Colonies: London and the Atlantic Economy 1660–1700 (Cambridge, 2010).