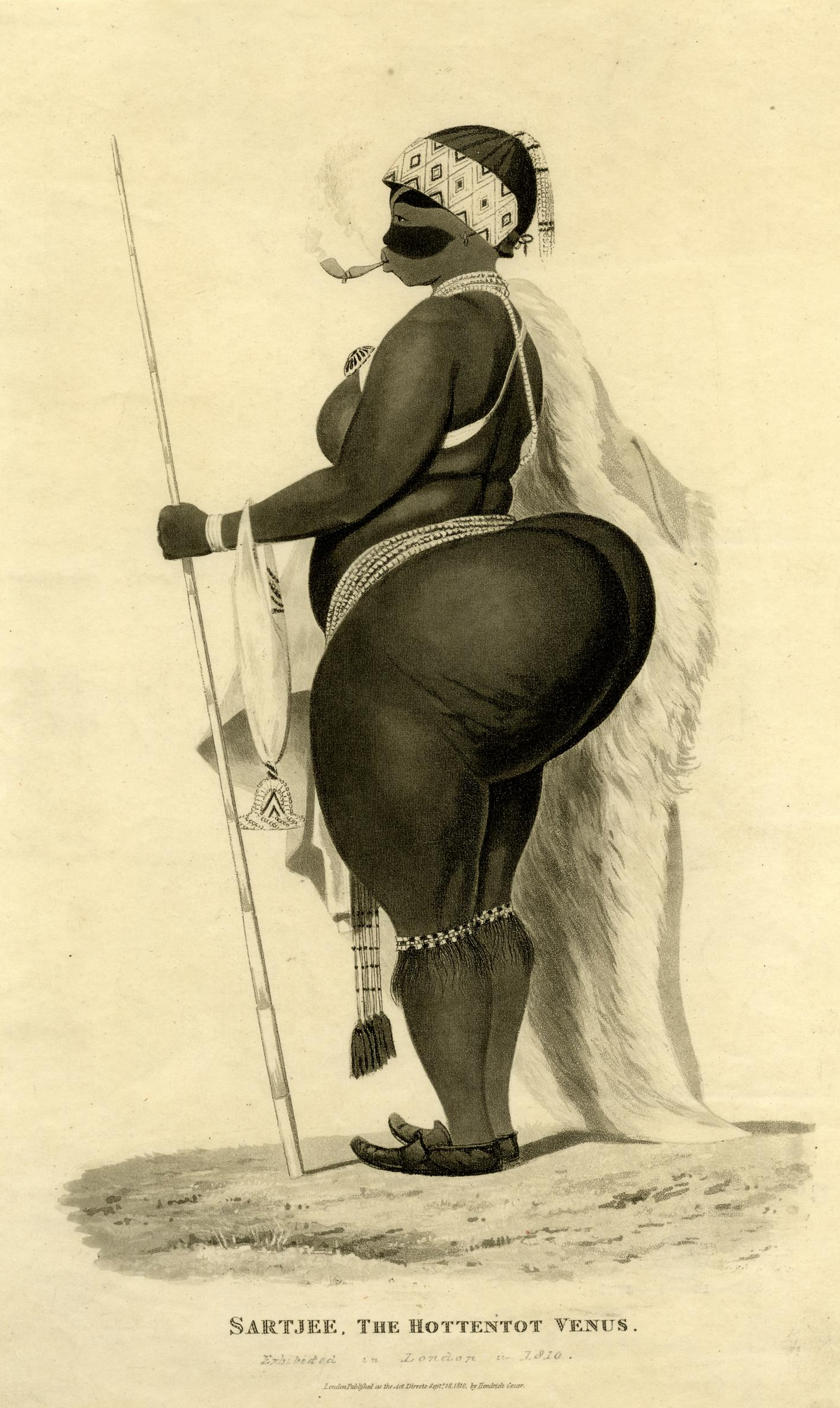

Published on 18 September 1810, this etching of Saartjie Baartman (1789–1815), who had recently arrived in Britain and came to be known as the Hottentot Venus, testifies to the contemporary obsession with exoticism. Born among the Khoikhoi people of southern Africa, Baartman’s life is perhaps one of the most striking examples of colonial exploitation. Subjected to Dutch domination in her childhood and adolescence, she was objectified by the British in her youth, and was dehumanised by the French for the rest of her life and beyond. Histories of her display in the freak shows of London and Paris in the course of the long eighteenth century bring into focus torturous episodes of violence and humiliation. These were justified as legitimate scientific curiosity regarding her body, based on polite standards of respectability and refinement. Standing exposed on the imperial stage, Baartman’s (mis)treatment at the hands of the metropolitan populace overstepped the premises of Enlightenment virtues of dignity and propriety that were so dearly prized. The repatriation and reburial of her remains in 2002 in her homeland were acts of restoring of the vestiges of personhood that she had been denied by the western world.

A closer look at Baartman’s image reveals that she is smoking a pipe. Intoxication thus becomes an accoutrement to her heavily sexualised and racialised body. As a historian of the British Empire, I view the contribution of the Intoxicating Spaces project as two-fold: first, highlighting the importance of colonisation and slavery as a driving force in ensuring a steady supply of ‘new’ intoxicants like tea, coffee, sugar, tobacco, opium, cocoa, and chocolate, which had come to be increasingly valued in European life and culture by the mid-eighteenth century; and, second, demonstrating how the consumption of new intoxicants resulted in Europeans’ close correspondence with the rest of the world, while enabling them to assert their own position within it. My research for the project’s online exhibition has focused on how visual culture registered the material and sensory transformations that followed the introduction of these commodities. Visuality is key to understanding early modern people’s relationship to intoxicants, and the role of intoxicants in shaping their responses to the political and economic developments of the period. Imagery and representation exoticised these imports and facilitated new forms of sociability that made Empire a lived reality at home.

Saartjie Baartman’s image stands in contrast to many of the images of people of colour I examined as part of the project. Black African figures were a staple in the visual culture, and visibility, of new intoxicants, where – similar to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s opium-induced dream of the mysterious landscapes of Xanadu – there was a close association between these novel substances and ‘exotic’ people. The representation of a collared black page boy waiting at a table laden with intoxicants in a domestic space (above) resonates, for example, with that of a ‘blackamoor’ featuring in the trade card for a business selling fine teas, coffee, and chocolate (below). Blackness in these images functions as an attribute in the theatrical sense, generating a politics of desire that made intoxicants more appealing in the republic of taste. The etching of Baartman smoking, however, is not about familiarising Europeans with new intoxicants. Rather, the image here unifies the consumer and the consumed, both of them being exotic. What does it mean when a displayed African female is represented as performing an action in public that was part of the imperial self-representation of the European male elite?

My reading of Baartman’s portrayal is based on European attitudes towards Khoikhoi practices surrounding intoxication, and towards African women. Caught between the age of dioramas, panoramas, and pleasure gardens on the one hand, and the pre-eminence of international expositions on the other, the image sets the tone for an aesthetic formulation of the idea of colonial difference. Intoxication is not only an important field in the articulation of difference but, when viewed in terms of visual representation, provides insight into how racial prejudices became commonplace in everyday life. Intoxication was both an instrument of dominance, and a way of castigating the native as uncivilised, backwards, and lazy. European understandings of indigenous cultures of intoxication were informed by the increasing commercialisation of intoxicants in their own societies. Tobacco was the chief commodity of exchange between European traders, travellers, and colonialists and the Khoikhoi. While Europeans viewed tobacco as a means of favouring, pacifying, and – ultimately – keeping the indigene under control, to the Khoikhoi tobacco had ritual and medical importance. European ideas about intoxication among the Khoikhoi are the product of the tumultuous era when their dominion, though on the rise, was faced with recalcitrance and also outright resistance. Racial hierarchy, in this regard, became a conduit for the anxieties of imperial power, yet strengthening its very exercise.

For European naturalists in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, non-European women were an anathema as they did not conform to their ideals of race and gender. However, while European femininity came to be celebrated, non-European women, and African women in particular, became embodiments of perverse, uncontrollable sexuality. The scientific gaze on the non-European female body tended to become prominent in an age when the promiscuity of white European men in the colonies was under scrutiny. Branding non-European women’s sexuality as dangerous insulated them from allegations of immorality, even as they continued to exploit the sexual labour of women of colour.

Returning to Baartman, her image speaks to wider European associations of non-European women with smoking. For example, in eighteenth-century India, a number of elite ‘Mohammedan’ women were depicted by British artists as smoking huqqa in their diaphanous attires. Such representations were an expression of supposed moral laxity as a counterpart to Oriental despotism. In Baartman’s case, smoking can be understood as signifying excess on the part of Africans, especially when Europeans in southern Africa frequently accused locals of stealing tobacco. Baartman’s arrival also coincided with the development of anti-slavery campaigns. When her heinous treatment was called into question, Baartman’s employers drew up a contract proving that she had willingly agreed to be an object of display. The presence of the tobacco pipe, in this context, added to the ethnographic authenticity of the image, while bolstering the position of her employers as having mastered the alien through pacification.

Exploring the visual in the history of intoxication helps us think about how identity formation was predicated not only on definitions of the self, but also on those of the other. The relationship between colonialism and intoxication can be useful in the re-evaluation of intoxicating spaces and practices, thus bringing us closer to the larger, unsavoury realities of some our favourite soft drugs.

Further Reading

- C. Crais & P. Scully, Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus: A Ghost Story and a Biography (Princeton, 2009).

- J. Crush & C. Ambler (eds), Liquor and Labor in Southern Africa (Pietermaritzburg, 1992).

- S. Qureshi, ‘Displaying Sara Baartman, the ‘Hottentot Venus’’, History of Science 42 (2004): 233–57.

- L. Schiebinger, Nature’s Body: Gender in the Making of Modern Science (Boston, MA, 1993)

- A. Sparrman, A Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope: Towards the Antarctic Polar Circle, and Round the World : but Chiefly into the Country of the Hottentots and Caffres, from the year 1772 to 1776 (London, 1785).

- L. Working, The Making of an Imperial Polity: Civility and America in the Jacobean Metropolis (Cambridge, 2019).