It was an honour for the Wellcome Collection to join Intoxicating Spaces and a group of eminent scholars for an online workshop that took place on 21–22 January 2021 on Modes of Persuasion: Humour and the Promotion and Control of Intoxicants Past and Present. The workshop was originally suggested by Angela McShane while she was head of Research Development at Wellcome Collection. It was a good choice of subject, as the humorous treatment of stimulants and narcotics by promoters and controllers is a significant theme in the Wellcome collections. The main aim of the event was to show how playfulness, levity, satire, and wit have historically been used to inform campaigns and communications around licit and illicit drugs.

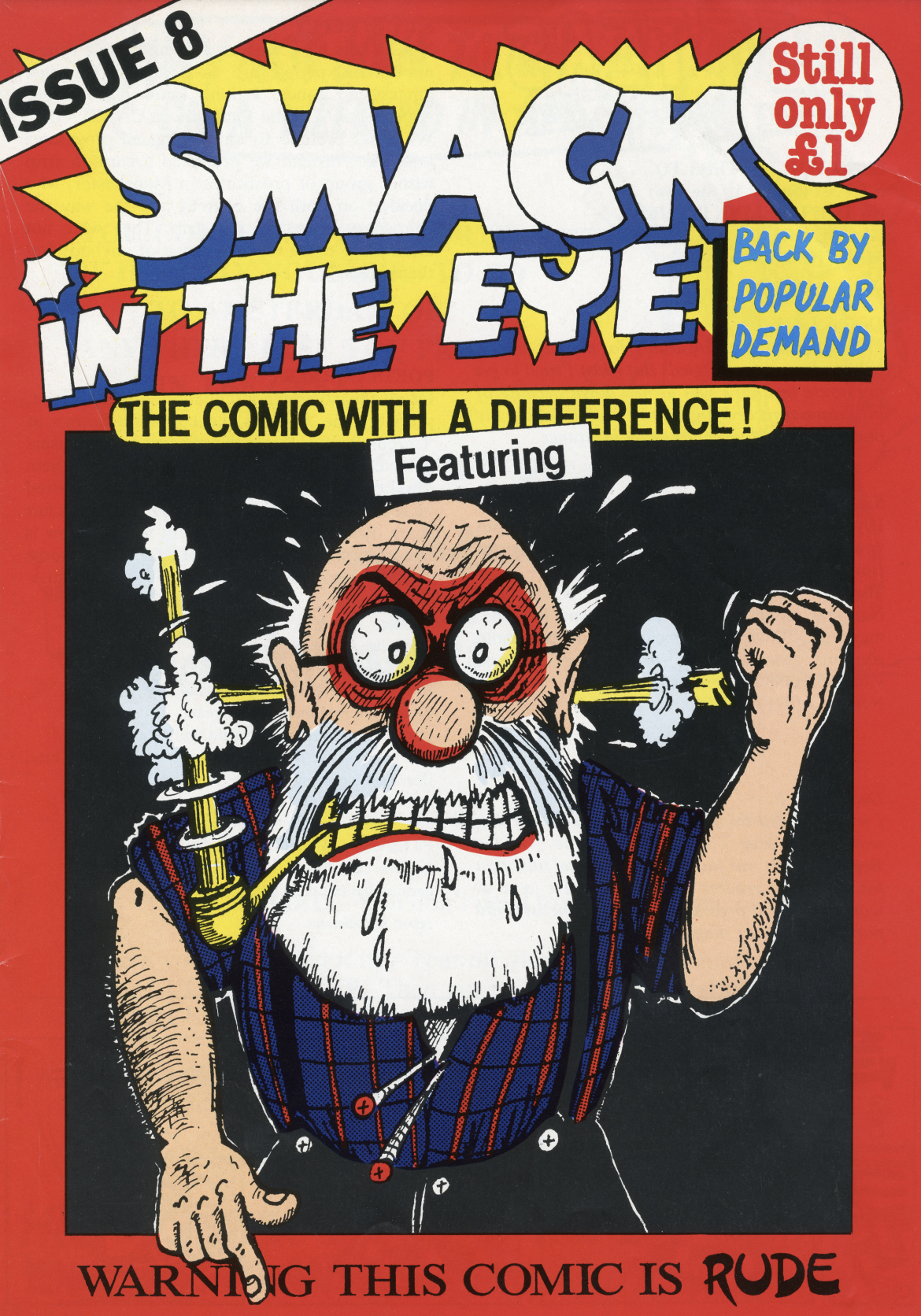

The first session on Materials, co-convened by myself and Eoin O’Cearnaigh, focussed on the Wellcome Collection’s resources. Peder Clark (University of Liverpool) spoke about the Viz-like graphics found in a comic called Smack in the Eye (1987–96), produced in Manchester by the Lifeline Project: they were drawn by the artist Michael Linnell, and donated to Wellcome Collection by the DrugScope organisation in 2016. They show efforts at the time to depict and profile drug users and lifestyles in cartoon form with a view to harm reduction. Cynthia Roman (Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University) told us about drunkards’ progresses from The Bacchanalians (a very rare adaptation of William Hogarth’s 1732 engraving A Midnight Modern Conversation) to the Grays Inn Road radical Charles Jameson Grant (active 1830–52) and the contemporary cartoonist Martin Rowson, whose Cocaine Lane updates Hogarth’s Gin Lane of 1751. William Schupbach (Wellcome Collection) then introduced the history of nitrous oxide or laughing gas, which was discovered in Bristol by Humphry Davy in 1799, became a popular party trick after Davy promoted it at the Royal Institution in London from 1801, was transformed into an anaesthetic for dental surgeons by a group of American dentists in the 1840s, and was recently revived as a recreational drug called Nos or Whipits (from its legal use in making whipped cream). William alternated Georgian caricatures on the subject by James Gillray and Robert Seymour with articles on nitrous oxide found in the long-running journal Chemist & Druggist.

In the following session, Promotion & Celebration, Kate Davison (University of Sheffield) explored the whimsical work of Ned Ward (1666–1731). He was not only a poet, authoring The Delights of the Bottle in Hudibrastic verse (1720), but also a tavern-keeper, host of The Bacchus in Moorfields. Kate elucidated the significance of wine-drinking among the mainly male and professional classes in London at the time. Yes, people did imbibe drinks other than gin in the eighteenth century! The following paper by Steve McKevitt (Leeds Beckett University) was particularly interesting for historians, as Steve spent his career in the advertising and media industries before becoming a professor of brand communications. He showed us some of the emotional and narrative principles and tricks underlying ads for McEwan’s lager, Bacardi, and Anadin, many of them pioneered by the firm of Collett Dickenson Pearce. Finally, Bob Nicholson (Edge Hill University) gave us an introduction to American cocktails as they were experienced in America by Charles Dickens, taken up by British bars in the 1890s (still with American branding), and much favoured by women drinkers. One delight of Bob’s talk was the bizarre vocabulary (such as ‘Corpse Reviver’ and ‘Sherry Cobbler’) invented by creative bar staff to promote and celebrate the cocktails. For further insights into the comic sensibilities of the Victorian age see Bob’s Twitter feed @VictorianHumour.

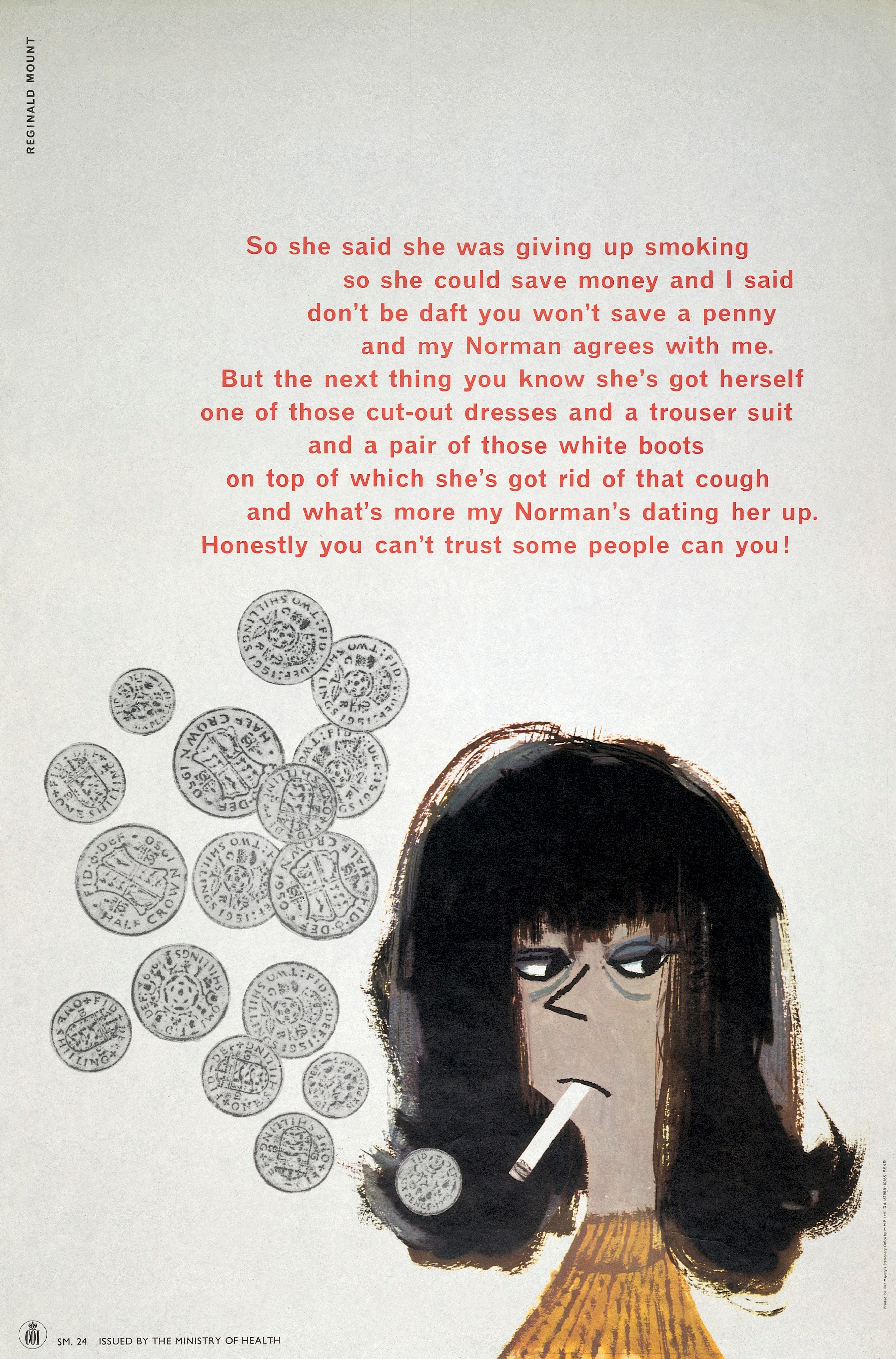

The third and final session was on Control & Demonisation. James Brown (University of Sheffield) charted the intoxicating worlds of caricaturist George Cruikshank (1792–1878), an especially interesting subject as the artist spent his early years drinking heavily in the riotous world of Regency London, but around 1844 experienced a Damascene conversion to temperance and teetotalism. James analysed a little-known sequence of lithographs by Cruikshank in the Wellcome Collection, The Progress of Mr Lambkin, in the Pursuit of Pleasure and in Search of Health. Lambkin is led by his convivial friends into alcoholic incapacity, but then brought back from the brink, though still in danger of relapse. James compared this sequence with Cruikshank’s later series The Drunkard’s Children (1848), the more expansive and interesting sequel to his better-known The Bottle (1847). Alex Mold (LSHTM) explored humour and anti-intoxicant campaigns in Britain in the period after World War II. The Central Council for Health Education in the UK was not averse to using shock tactics, disgust, and gallows humour, while employing distinguished designers such as Reginald Mount and H. M. Bateman. Tobacco, alcohol, and heroin were among the subjects of their poster campaigns. The last, jointly authored paper in this panel focused on the sixteenth century. Emma Rhatigan (University of Sheffield) brought together attacks on intoxicant-users in sermons, such as those by the celebrity preacher Henry ‘Silver-Tongued’ Smith (1560–91). Drunkenness was described as bestial or subhuman, a gateway sin (the infamous ‘slippery slope’), and typically ‘German’ (though the English were catching them up). Cathy Shrank (University of Sheffield) discussed Pierce Pennilesse his Supplication to the Divell, a short prose work by Thomas Nashe (1567–c.1601) whose verbal inventiveness in laughing with rather than at habitual drinkers shows as much creative and bizarre wordplay as the American cocktail mixers of the Victorian age.

So many different cultures, disciplines, periods, social groups, professions, and substances – the variety was itself intoxicating! To draw the threads together, Phil Withington (University of Sheffield) introduced commentary from two experts with practical, present-day experience of these matters: Peter Rice, consultant psychiatrist advising Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems, and James Nicholls, CEO of Transform Drug Policy and author of (inter alia) The Politics of Alcohol: A History of the Drink Question in England (Manchester, 2011). They identified vital changes in technology and graphic styles from the seventeenth century to our own times, the value of humour in approaching the ambivalent elements in drug consumption (habitual consumers both love and hate their substances of choice), and the importance of the mythology surrounding various intoxicants, from the ‘gin craze’ and nitrous oxide parties to Bob Dylan’s memoirs. James Nicholls found shared qualities in laughter and intoxication: both are transgressive, a challenge to everyday self-control, and strongly influenced (whether we realise it or not) by the Romantic concepts and innovations of the early nineteenth century. And he reminded us that ‘behaviour-changing messages are owned by the recipients’: the consumers of drugs can re-appropriate and invert them beyond the reach of moralists and authorities.