Alfa Academy

Next to water and coffee, tea is the most preferred and imbibed drink on earth. People drink it when they get together, as a moment to calm down or wake up. In this blog we take you on a journey through time on the basis of the following question: what were the rituals around tea at the time of the Dutch Republic, and how have these changed over the years until our tea moment now?

China: The Origin

Tea is an important part of Chinese culture. The Chinese were the first to consume tea. There are various legends about the origins of tea involving monks and/or emperors, but it is estimated that until 3000 BC tea was used as medicine. Acupuncture and so-called ‘herbal therapy’ are important pillars of Chinese medicine.

We know for sure that tea became a more widely popular drink in China around 300 AD. Teahouses were set up all over the Chinese empire and tea became an important part of Chinese culture. Many books, poems, songs, and paintings were dedicated to tea and the tea plant. Around 900 AD the use of tea also flew over to Japan. Unlike the Chinese, who saw tea drinking as a form of relaxation, the Japanese elevated tea drinking to an art form. Drinking tea was accompanied by numerous ceremonies and learning this art could take years.

Tea in the Dutch Republic

Tea Supply in the Netherlands

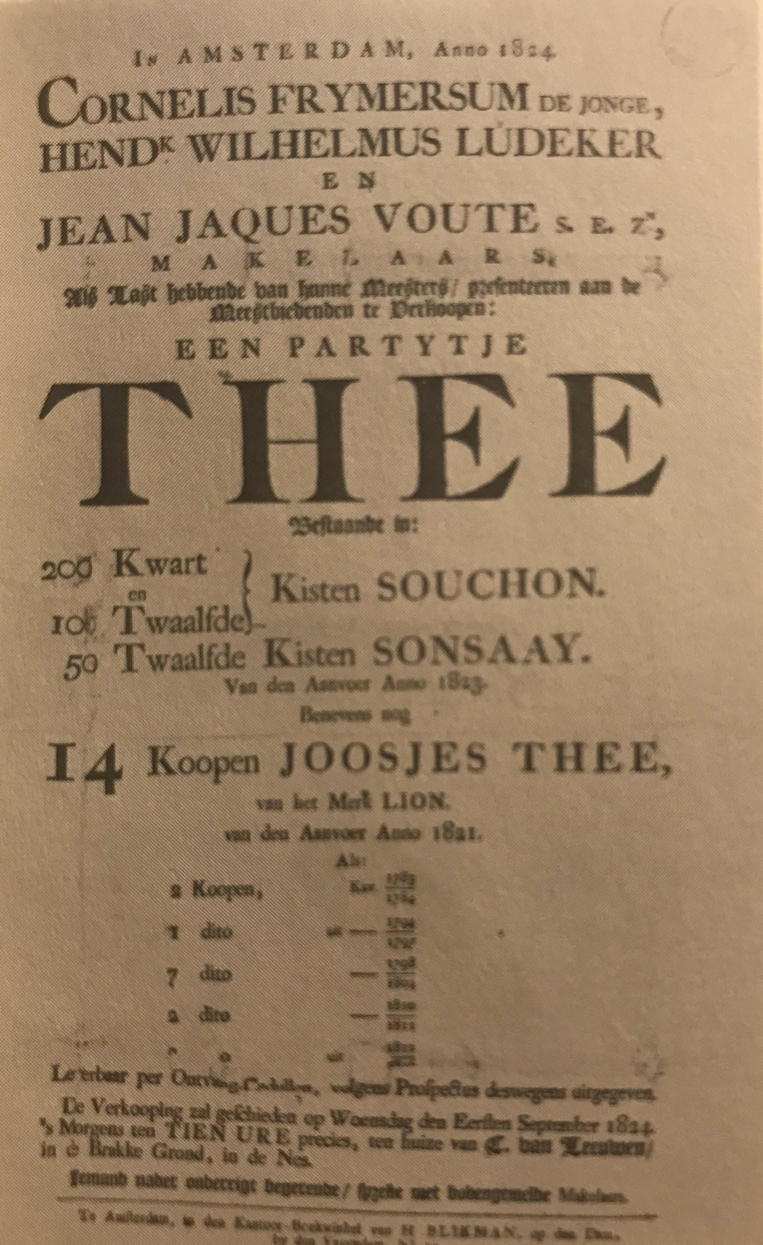

The VOC and its competitors from other European countries, in particular the English, sourced their tea mainly from the Fujian province of China. China initially did not want to trade directly with foreign countries. This is why in the seventeenth century the VOC bought its tea from Chinese ships arriving in Batavia. After most of its European competitors came into direct contact with China in the first decades of the eighteenth century, the VOC also opened a direct trade relationship between the Dutch Republic and China in 1728. Once tea arrived in the Netherlands and was introduced to the elite, demand for it grew enormously. The VOC issued pamphlets stating when a particular product, including tea, would be auctioned. A large number of merchants in the eighteenth century entered the tea trade.

Tea for Medicinal Purposes

Many of the VOC’s travel reports which deal with China and Japan contain a great deal about the use of tea in those countries. They often refer to the fact that tea has a beneficial effect on health. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the medicinal qualities of tea were praised by many experts but also strongly disputed. One of the first Dutch doctors to recommend the use of tea as medicine was Dr Nicolaas Tulp (1593–1674). In his work ‘observationes medicae’ (1641) he mentions several ailments against which tea could be used as a medicine. Opponents of doctors such as Nicolaas Tulp were mainly abroad and believed that the drink was unhealthy for your body.

Tea Among People

It is well known that tea was first introduced as a fashionable and expensive beverage that could only be consumed by the elite. The elite wanted to taste the most special and exclusive tea as a matter of status. They even had rituals around tea drinking. For women in particular, tea drinking was of great social significance. While the men maintained social contacts in coffee houses, clubs, and other places, women met up around the tea table. Gentlemen also drank tea but only indoors and with their wives. For example, after a long walk they might want to relax with a nice, hot cup of tea.

The question that follows is: at what time did people usually drink tea? Tea-drinking ladies groups usually met around two o’clock, immediately after lunch. Gradually, this time was moved to 5 o’clock, adopting the English habit of ‘5 o’clock tea’. Typically, a tea afternoon included not only a decent amount of tea but also sweets and alcoholic drinks to finish it off. Some people used expensive French jams, others found something like marzipan to be enough. Later, biscuits such ‘theerandjes’ and tea biscuits were added.

In addition to these delicacies, it was important that the setting of the tea also looked very fine. Many houses had a specially equipped room to consume the tea, also called the ‘the comptoorje’. Because of the origins of tea, these were furnished with all kinds of Asian accessories and works of art, such as porcelain and special oriental tea utensils. In houses without a special tea room, tea was usually consumed in the front of the house. Another very special feature of drinking tea in the eighteenth century is that people often drank it from the saucer because the tea cooled down quicker this way. Teacups with ears can therefore only be seen after the eighteenth century.

Tea Outdoors

Although tea is often thought to have been consumed mainly at home in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, distinguishing it from coffee and alcoholic beverages, nothing could be further from the truth. There were many tea houses located in Amsterdam, mainly situated near the dam. Along the rivers in the vicinity of Amsterdam, numerous tea domes offered space where one could hold discussions with business relations or acquaintances while enjoying a cup of tea. Tea domes are specially built for consuming tea, so one could say that drinking tea in a tea dome is the same as drinking tea in a cafe or teahouse. The elite of the Netherlands, who wanted to enjoy a hot day, drank their tea not only in the domes but also in the gardens of their country estates.

Shopping for Tea

Shopping for tea in the seventeenth century was very different from what we do now. Buying tea was almost a full-day activity. People (the elite) went to a shop for tea and did a kind of tasting there. The selection was not huge; you could choose from about seven different kinds of black tea. The owner of the tea shop was usually an expert in the field and helped the customers with tasting the tea. Tea was tasted in the way we now taste wine: the tea was kept in the mouth for a while and then spat out. The owner of the shop tried to keep the palette of flavours as wide as possible and instructed customers as to how to prepare each tea and how long to let it brew. These tea shops also sold all kinds of accessories for the tea, such as teapots and tea filters.

We don’t recognise this scene at all any more. Due to developments during the industrial revolution, tea gradually became a mass product. It can be bought almost everywhere. We no longer know tea as a luxury product but as an everyday product that we can buy anywhere at any time. We now buy our tea in the supermarket (e.g. Albert Heijn or Jumbo) and the selection is huge. There are flavours (like rooibos with mango, blueberry muffin, and apple pie), and we are not usually able to taste the flavours of tea before we buy it. There are still some special tea shops to be found in the Netherlands, like the Simon Lévelt, but the ritual is still not anything like it was in the seventeenth century.

Tea Today

A Tea Moment in the Present

Today, tea is already firmly embedded in Dutch culture. Making and drinking tea is no longer only reserved for the elite and a complete ceremony is no longer required. What does a tea moment look like in contemporary Dutch culture? This part of the blog looks at current Dutch tea culture.

Nowadays, tea is no longer regarded as a status-enhancing consumer good but as a consumer good that promotes atmosphere and social life. It brings people together and it is seen as something casual – ‘just have a cup of tea’. Tea is considered a habitual drink that is linked to a healthy life in similar ways as drinking water is associated with staying hydrated. Tea is also embedded in a metaphorical sense in the Dutch language. The saying ‘spill the tea’ is widely used, referring to the retelling of a dramatic event or gossip; the pronunciation was originally ‘spill the T’, where ‘T’ stands for ‘Truth’. This phrase was popularized by the TV show RuPaul’s Drag Race and a similar use of T for truth appears in John Berendt’s bestselling 1994 novel Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

Tea as a Fast-Growing, Diversified Consumer Good

Tea shifted from a privileged consumer good in the pre-modern period into a mass produced consumer good from the later part of the nineteenth century. The industrial revolution had a great influence on the availability of tea flavours and tea types. There was more room to experiment with flavour blending in Dutch tea factories. A nice example of a completely different flavour and type of tea is herbal tea. This type of tea does not originate from the tea plant but from totally different plants such as mint or chamomile. The current Dutch tea market is all about demand and supply and the expansion of the range of tea products. It is also about fierce competition between big companies like Unilever (Lipton), Sara Lee (Pickwick), and Associated British Foods (Twinings). As a result, tea profits have declined, and Unilever is even planning to sell its complete tea business unit.

In Northwestern Europe, the consumption of strong and bold black tea is decreasing, while the demand for green, herbal, and flavored teas is growing steadily. In the Dutch supermarket you can literally find more than 50 different blends. Tea can be found next to the coffee shelves and close to the biscuits and cakes section. Organic tea is considered the latest fashion in tea drinking and it is widely advertised as ‘hip and happening’. All brands try to jump on the organic tea bandwagon. Typically, a Dutch family in the Zeist area will drink a cup of tea in the morning with breakfast, in the afternoon with a biscuit, and a cup of a special organic sleeping blend in the evening.

Twenty-First-Century Dutch Tea Houses and Tea Gardens

In the Netherlands, many authentic tea houses and gardens have been preserved. We often see them along rivers and roads. In the eighteenth century, tea houses were places of status and prestige. Today, they are considered social meeting places for all. Take, for example, the tea house of Zeist Castle, restored to its former glory in 1960 but open to all visitors without any restrictions. My grandfather, Mister van Capelle, was an architect and contributed to the restoration process.

Conventional tea houses are no longer being built. What we do see, however, are alternative tea houses and gardens being set up. One example is the Les Abeilles tea house in Zeist. Its terrace overlooks Zeist castle and the informal design of the building creates a homey, warm atmosphere. Another example is the modern tea and pancake house Rhijnauwen in Bunnik along the river. This tea house was built by the Utrecht municipality in 1921 as a casual meeting place in a park setting for its citizens. What is typical in tea houses nowadays is the child-friendly nature of the setting. There are often playgrounds and spacious areas for children to play and the menu is ‘child proof’

Conclusions

Tea has taken a long journey to become what it means in our society today. We have seen how the tea ritual originated in China and was customised within the context of the Dutch Golden Age. Initially tea was only for the elite, with special types of black tea that was consumed from exclusively Asian tableware. In the nineteenth century, tea became a mass-consumer product that was and is associated with moments of conviviality and refreshment. The tea houses of the past are part and parcel of Dutch cultural heritage and co-exist alongside more contemporary, privately-owned tea corner or tea garden settings that provide child-focused services.