One of the key sources we’re using to reconstruct the intoxicating spaces of our four case study cities are the so-called ego documents that proliferated across our period: diaries, letters, memoirs, and travel accounts. Some of the UK’s best manuscript holdings of these sources can be found at the Bodleian Libraries in Oxford, so last week saw me on a train to the crisp and autumnal dreaming spires to work through a selection. Ensconced in the wonderful Weston Library, I started with London diaries – including that of a country parson from Oxfordshire who seems to have spent most of his time in the capital purchasing different varieties of tea from Twinings – and, having finished those, turned my attention to their excellent collection of seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century correspondence. This consists of c.50,000 letters, all abstract-searchable within Early Modern Letters Online, an incredibly useful resource created by the Cultures of Knowledge project.

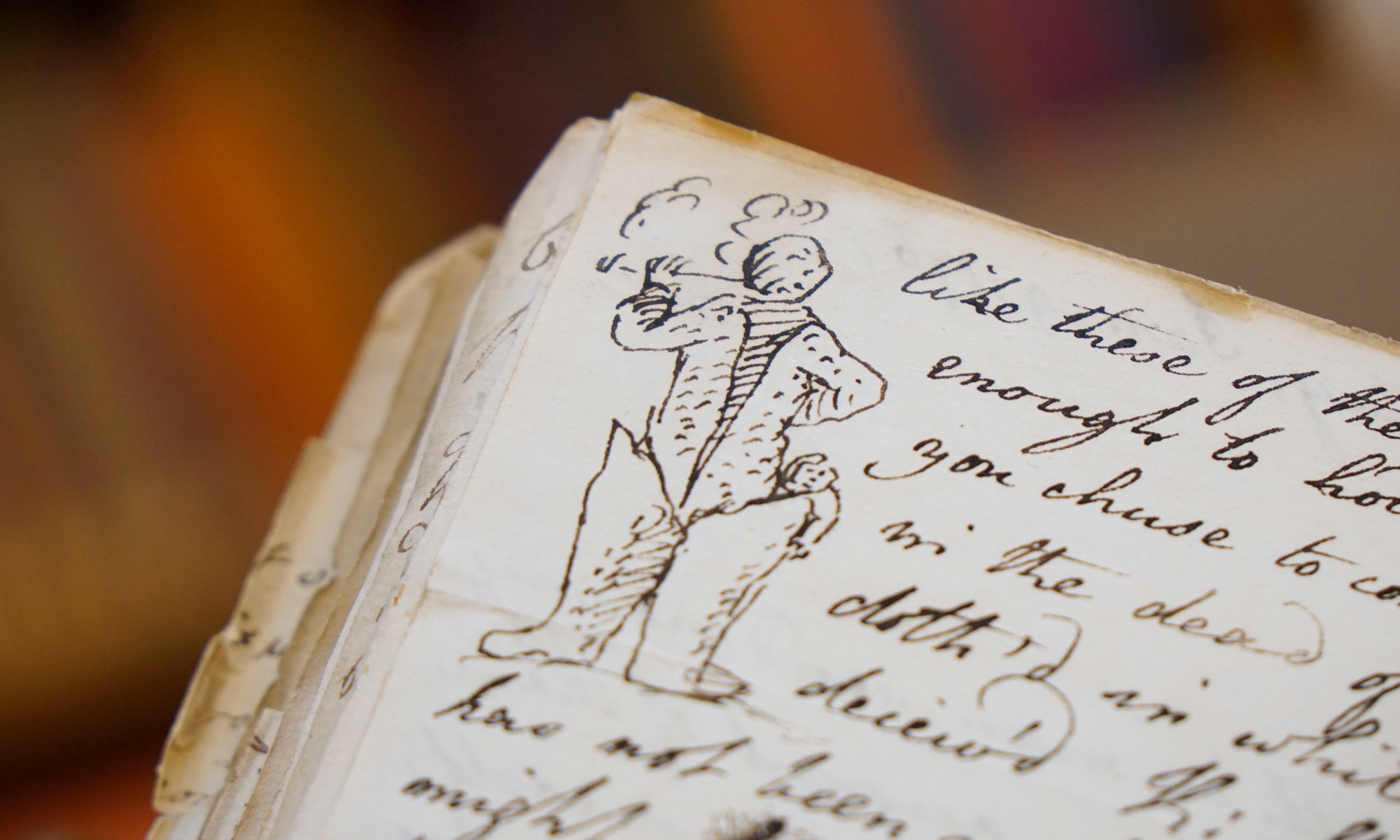

I ordered up this letter, between little-known eighteenth-century antiquarians Richard Gough and Edward Haistwell, in which the former asks to meet the latter at the Turk’s Head coffeehouse in Exchange Alley in the City of London (the pair conducted an extensive epistolary and IRL bromance throughout the 1760s, mainly organised around metropolitan assignations over coffee or tea and the arrangement thereof). As a historical doodle enthusiast, I was delighted to see in the margins of the missive a sketch of a table laid with wine, glasses, and writing implements. Indeed, the rest of their c.350-item correspondence, now bound as a single MS volume, is replete with over fifty charming drawings, mainly composed by Haistwell. Several of these visual paratexts feature new intoxicants; like many amateur cartoonists of yore, Haistwell had a particular fondness for rendering pipe smokers, perhaps because they were easy, or because the form of smoke pleasingly mirrors and complements the cursive handwriting of the long eighteenth century.

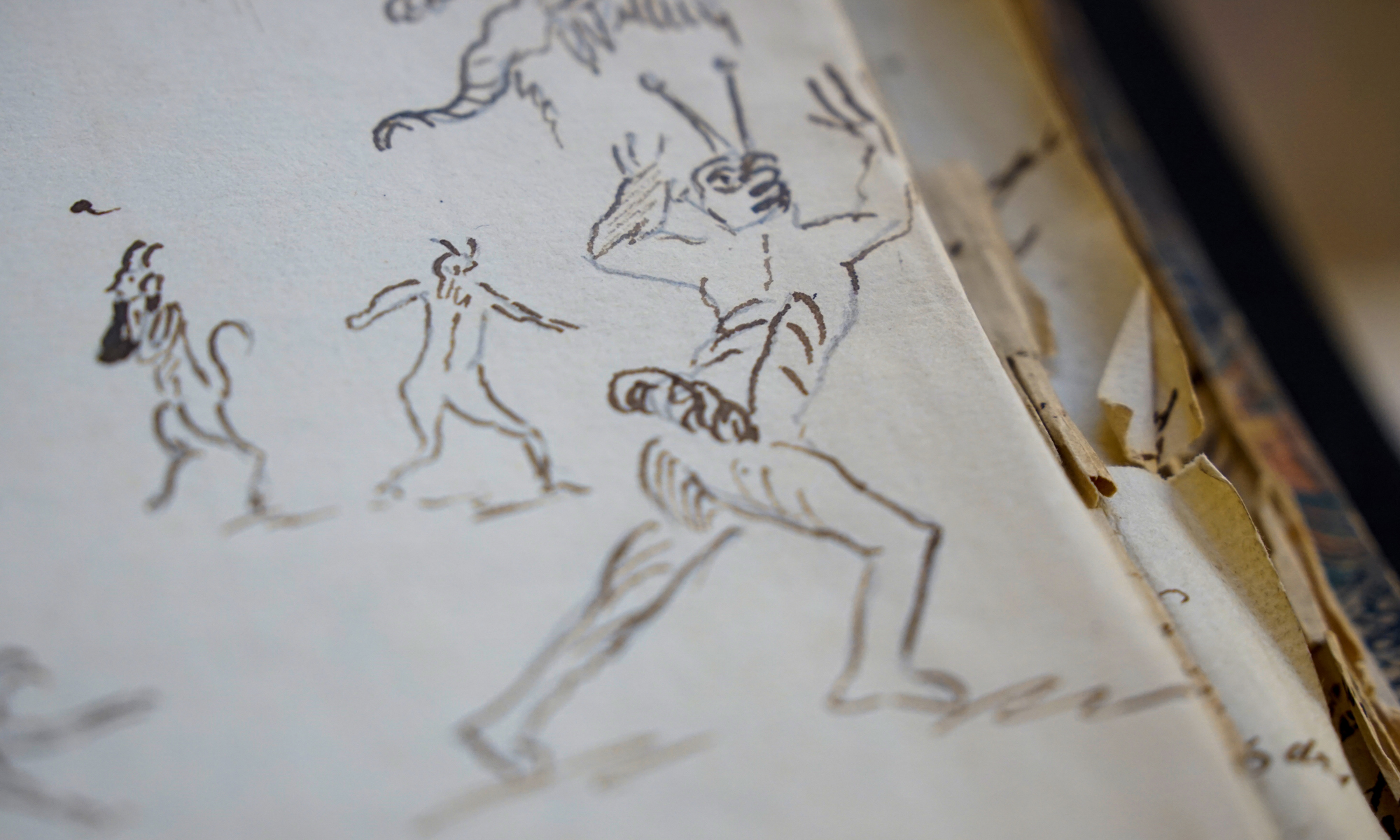

Others have a distinctly Halloween-y vibe, including two officials confronting a defiant necromancer; a fantastically creepy skeleton playing the xylophone; an oddly sinister black-eyed figure sitting under a tree making music for a dancing dog; and a theatrical insect man, one of several hybrid fiends fleeing from a cross.

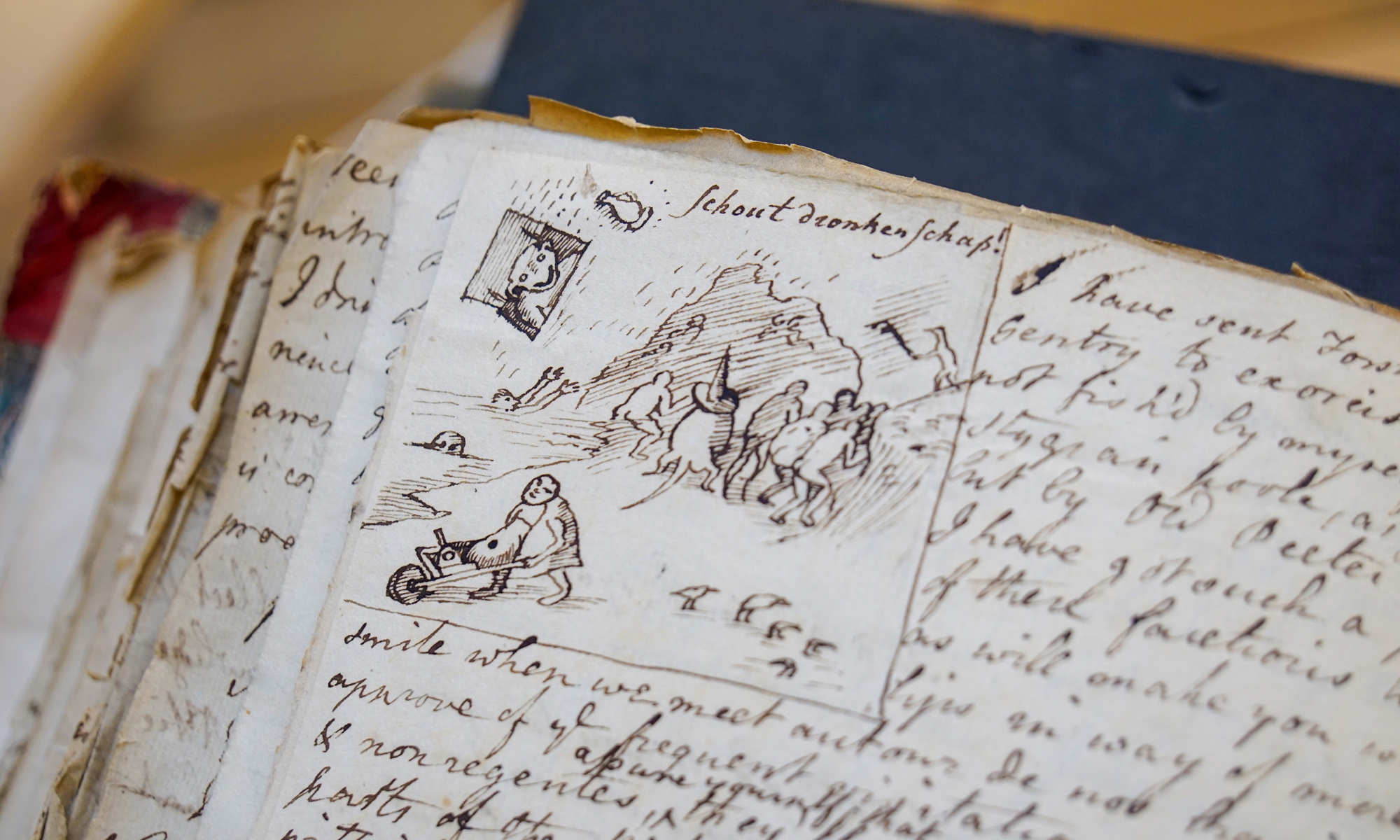

Chilling as these specimens are, I was especially struck by this image in a 1763 letter from Haistwell to Gough. It’s a terrifying tableau populated by grotesque figures, a devil’s likeness, and people drowning and with distended bellies, which – via its wine jug and Dutch slogan ‘schout dronkenschap!’, or ‘observe drunkenness!’ – seems to conjoin the spooky and the intoxicating in ways appropriate to both project and season.

What’s going on here? The body of the letter suggests that, like most of Haistwell’s etchings, the ‘evil spirits’ served no deeper or more profound purpose than to cheer Gough up; the ‘pandemonium of these facetious little fiends’, he writes, ‘will make you wag your lips in way of more than [a] smile… & drive away Melancholy with its green ey’d visage’ (earlier in the letter, Haistwell thanks Gough for helping him through and out of his own ‘[s]lough of Despond’, offering to compensate him with ‘a little bit of honeycomb & a piece of pomegranate’).[1] Moreover, Haistwell admits that the characters were ‘not fish’d by myself out of the stygian poole… but by Old Pieter Brueghel’, and this, together with the tell-tale caption, confirms that the doodle is not original but rather repurposes characters and vignettes from Dutch artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1558 depiction of Gluttony (or Gula), part of his Seven Deadly Sins series.

This engraving, which partakes of Bruegel’s career-long preoccupation with sinful culinary overindulgence, depicts a vivid and genuinely frightening intoxicating space, presided over – as in the other prints in the series – by a female figure, quaffing from a jug and perched on a pig, who embodies the vice in question. As in Haistwell’s droll repurposing, humans, demons, and monsters eat and drink to excess from barrels and around tables – sometimes to the point of vomiting – in a bizarre waterside hellscape comprised of strange taverns, bare-limbed trees, and anthropomorphic force-fed windmills. The marginal mottoes, provided here in full, read EBRIETAS EST VITANDA, INGLVVIESQUE CIBORUM (‘One must avoid drunkenness and gluttony’) and Schout dronckenschap / en gulsichlijck eten Want ouerdaet doet godt en hem seluen vergheten (‘Observe drunkenness and gluttony, for excess makes one forget God and forget oneself’). Something to bear in mind if you’re out trick or treating or otherwise celebrating tonight…

[1] This language is typical of Haistwell’s affectionate, playful, verbose style, which evidently irritated the Bodleian cataloguer; it is described in this letter as ‘nonsensical gay conceit’, and in others as ‘high flown facetious effusion’, ‘florid allusiveness’, ‘imaginative outpourings’, ‘prattle’, ‘verbiage’, ‘extravagant surmises’, ‘long outlandish discourse’, and – my favourite – ‘erudite pleasantry gone mad’.