1784 and the European tea market was in upheaval. The most lucrative part of the continental East India trade had suddenly been undermined by a radical tax reform in Britain, the so-called Commutation Act of 1784. For decades, East India companies based in France, Scandinavia, and the Low Countries brought a vast amount of tea to Europe. The tea was sold to smugglers who supplied the black market in Britain, where tea was taxed heavily, often well over 100 percent. According to some estimates in the mid-eighteenth century, more than three-quarters of all tea consumed in Britain entered the country as contraband!

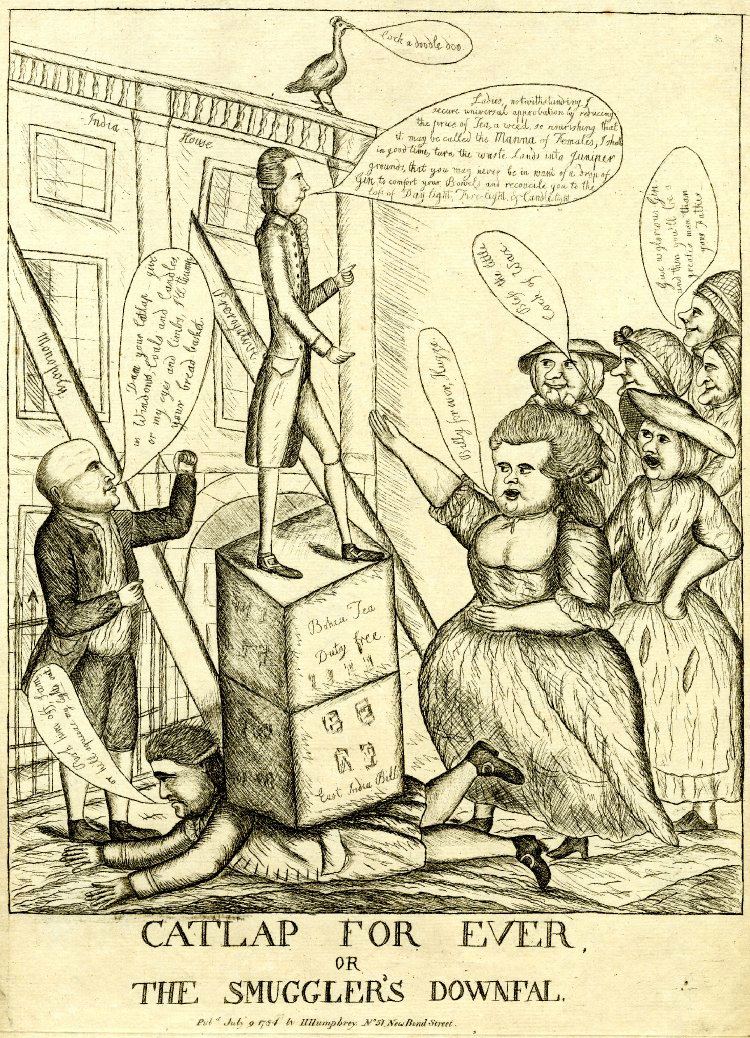

This satirical print by William Dent illustrates the effects of the Commutation Act. The tea smuggler is squeezed under the weight of two chests of Bohea tea, the cheapest black tea available to Europeans in the eighteenth century (most tea imported from China was Bohea). The term ‘Catlap’, a slang word for diluted watery drinks, indicates the quality of the brew. The handsome young man on the chests of tea is Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger himself. The man to the left of the chests condemns the Act, shouting: ‘Dam your Catlap – give in Windows, Coals and Candles or my eyes and limbs, I’ll trump you bread basket’. The lowering of the sales tax on tea was funded by – or ‘commuted’ into (hence Commutation Act) – increased taxes on windows, coal, and candles. Yet the increased imports of tea in the 1780s and 90s also entailed growth in revenues and the duties on tea continued to be an important source of state income. The ladies on the right, on the other hand, are heartily welcoming the Act as the price they paid for tea was halved. The image plays with gender and class stereotypes, and several of the women portrayed are poor and rude: ‘Bless the little cock of wax’ and ‘Give us glorious Gin and then you will be a greater man than your father’, they call up to Pitt.

Pitt authorized the Act on the advice of Richard Twining, the leading tea merchant in London and the future Director of the English East India Company (1793). In addition to the poor consumers of Britain, the EEIC was a great beneficiary of the new law. The imaginary political spectacle drawn by Dent is also taking place outside the ‘India House’, indicating the influence the company had over the fiscal reform. Within a few years of the Act, its tea imports more than doubled. Meanwhile, smuggling declined rapidly as did the volumes of tea imported from China by other European companies. Twining was the owner of the London firm Twinings, founded in 1706, and still one of the world’s leading tea traders.

By the late eighteenth century tea consumption had become widespread among British people, not at least among women. Like many other early modern fashions in Europe, tea-drinking was first picked up by members of high society. It was the Portugal-born Catherine of Braganza, queen consort of Charles II (1662–1685), who popularised tea within England. Its exotic origins (all tea from this period came from China), its medicinal status (it was introduced to Europeans as a drug), and its price (prohibitively high at the beginning) made tea a socially exclusive commodity. The prominent display of a tea box in Joseph von Aken’s c.1720 painting An English Family at Tea is indicative of its fashionable status and high price.

When the trade with China expanded in the 1730s, the consumption of tea in Europe increased sharply. Tea, which was easy to brew, became associated with domestic consumption and the sociability of women. The habits and customs of drinking tea evolved, and servants recycled the leaves used to brew their master’s and mistress’s tea. There was even a market for used tea leaves, and in Amsterdam vendors walked up and down the street with wheelbarrows full of secondhand tea. Within a few decades, tea drinking became widespread, not least in Britain. William Bigg’s 1792 painting A Cottage Interior: An Old Woman Preparing Tea illustrates how far tea drinking had traveled from Catherine of Braganza’s court in the 1660s to the end of the eighteenth century. And smuggling played no small role in this story.

The print Loading a Smuggler, made twenty years after the Commutation Act, demonstrates that tea smuggling continued to be an issue during periods of conflict; the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars had made the illegal trade in tea profitable again. The variety of tea being smuggled in the picture is not cheap Bohea, the origin of Catlap, but rather Hyson, an exclusive green tea. Loading a Smuggler also suggests that gin and coffee (concealed in the woman’s hat) were smuggled together with tea. There is ample historical evidence showing that smugglers dealt in many different commodities, although caffeinated goods and alcohol seem to have been a particularly common combination. For much of the eighteenth century the smuggling of such goods was carried out from France and Holland, in small boats carrying gin, or French brandy, and tea. The second half of the century saw the evolution of a direct trade between Scandinavia and northern England and Scotland. During its most prolific years, the two Scandinavian East India companies (the Danish Asiatic Company and the Swedish East India Company) accounted for about a third of all Chinese tea imported to Europe; and most of it was re-exported/smuggled to Britain. Scotland received a lot of this tea, including large quantities of another cheap black tea named Congo which was smuggled out of Gothenburg. In Scotland, it was simply known as ‘Gothenburg Congo’.

Further Reading & Resources

- M. Ellis, R. Coulton & M. Mauger, Empire of Tea: The Asian Leaf that Conquered the World (London, 2015).

- D. C. Janes, ‘Fine Gottenburgh Teas: The Import and Distribution of Smuggled Tea in Scotland and the North of England, c.1750–1780’, History of Retailing and Consumption 2 (2016): 223–238.

- H. Hodacs, Silk and Tea in the North: Scandinavian Trade and the Market for Asian Goods in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Basingstoke, 2016).

- H-C. & L. H. Mui, ‘The Commutation Act and the Tea Trade in Britain 1784-1793’, Economic History Review 16 (1963): 234–253.

- H-C. & L. H. Mui, ‘Smuggling and the British Tea Trade before 1784’, American Historical Review 74 (1968): 44–73.

- L. Müller, ‘The Swedish East India Trade and International Markets: Re-Exports of Teas, 1731–1813’, Scandinavian Economic History Review 51 (2003): 28–44.

- Richard Twining, Observations on the Tea and Window Act, and on the Tea Trade (London, 1784).