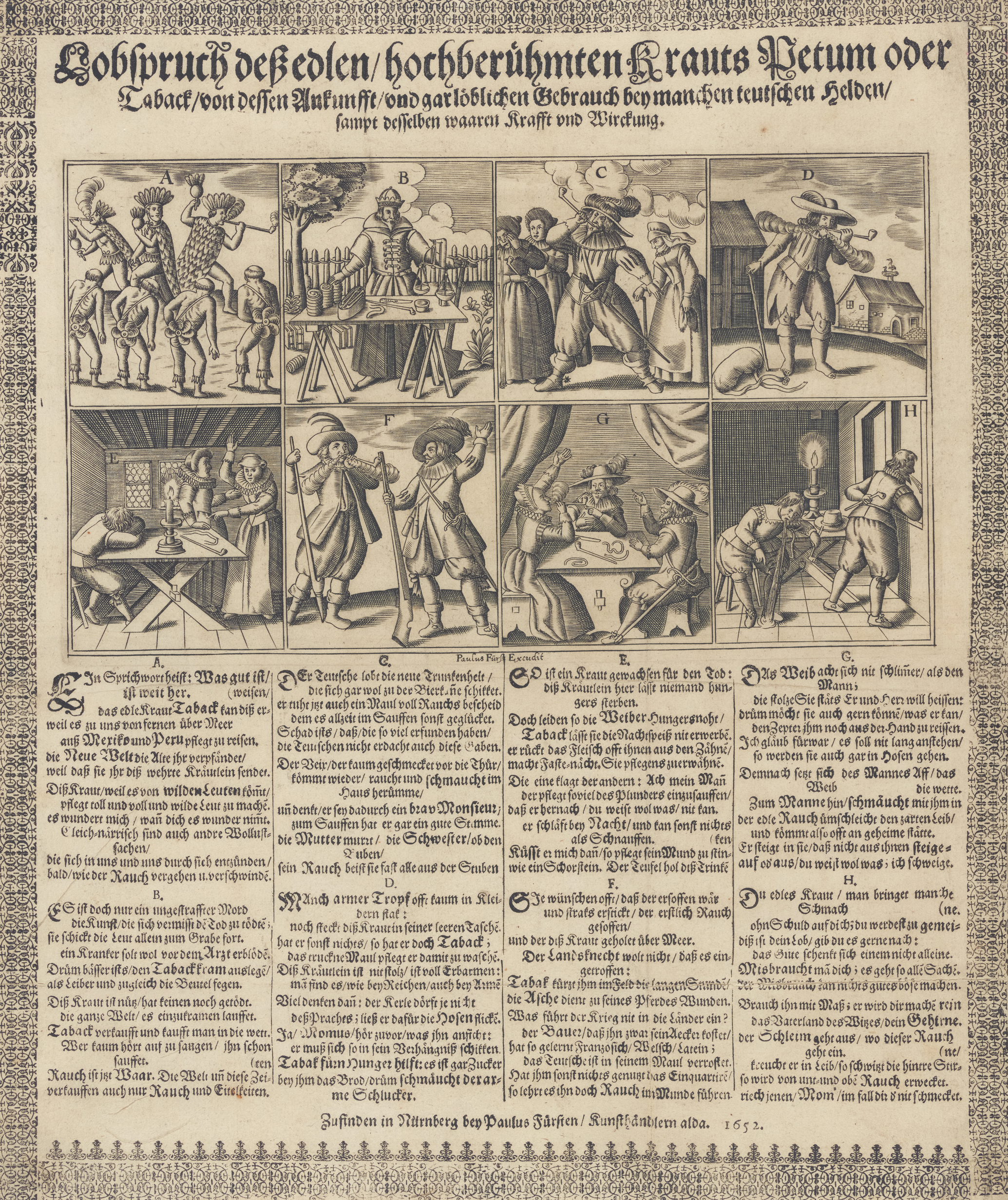

A German broadside published in 1658. Eight vignette etchings and a poem recount the story of tobacco’s arrival in Europe, and its ‘praiseworthy use by some German heroes/as well as the same’s real power and effect’. In the first image Native Americans, some adorned with feathered headdresses and smoking long pipes, appear to dance about with abandon.

The saying goes: What is good/comes from far away.

The noble herb tobacco is proof of this/for it journeys to us from afar across the seas from Mexico and Peru.

The Old World impawned to the New/because it sends the treasured little herb.

This herb/because it comes from wild people/Makes for romping and sozzled and wild people.

I am astonished/when it astonishes you.

Just as foolish are other revelries/that ignite in us and ignite us through them/ presently/to wane and disappear just as smoke.

Greatness and folly are bedfellows here: whilst the exotic tobacco is a valuable and highly prized commodity in the Old World, it also has the power to induce fleeting intoxication; to render the European into a wild savage. Such is the ambivalent tenor of the satirical broadside entitled Lobspruch deß edlen/hochberühmten Krauts Petum oder Taback (laudation for the noble/highly famed herb petunor tobacco), [1] published in Nuremberg by Paul Fürst (1608–66) with an accompanying poem by Sigmund von Birken (1626–81). Its imagery takes the reader on a smoky sojourn of the tobacco-induced highs and woes of mid-seventeenth-century German society.

But why satirize tobacco use in 1652? Europeans had been smoking tobacco since sailors returning from the New World introduced the habit in the late 1500s. Yet it was not until the English refined colonial plantation production in Virginia in the 1620s and domestic European crops took off that tobacco began to creep into everyday consumption on a larger scale. Historians widely consider the Thirty Years War (1618–48) as the catalyst for the diffusion of tobacco and tobacco consumption practices through Europe, not just to the cities but to remote and rural regions. In 1652 European peace was but a few years old, and tobacco was everywhere: on the street, in the home, in medical treatises, in broadsides, in art. And where many swooned about its utility, others found it a depraved nuisance. Its contentiousness made it a prime target for satire; but what exactly was this broadside mocking?

Market Medicine

In image B we see a learned doctor (signified by the books behind the trestle) who, instead of killing his patients with his cures before they succumb to their illness (‘the art/that measures itself on killing death’), now sells tobacco. Using his knife, he cuts lengths of tobacco from the coils on the table before weighing them on the scales. A pipe also lies on the table, suggesting that he sells utensils used by smokers, chewers, and snuffers. A garden fence, spade, and a tobacco plant in the background intimate that he is part of supply chain based upon domestic tobacco production, and that he perhaps even grows it himself (thriving in warm as well as cool climates, by the 1650s the tobacco plant had quickly advanced as a crop in many parts of Europe).

Whilst undoubtedly a nod to the role of learned medicine in popularising tobacco, this image-text simultaneously targets the medical fraternity. For the author, this topsy-turvy world where physicians (whose practice was supposed to entail reading urine, interpreting symptoms, and prescribing cures according to Galenic medical theory) metamorphose into hawkers of ‘snake oil’ has a positive side: it renders the murdering physician-scholar innocuous. ‘Thus it is better/to lay out tobacco wares/than to clean sweep both bodies and the [contents of] purses’, for tobacco is both ‘useful/has not killed anyone yet’ and lucrative for ‘The whole world/runs to buy it’. And yet, for all its goodness and popularity, tobacco is an addictive fashion as ‘who can hardly stop singing [its praises]/who drinks it’. The last line solemnly points to the sham and ephemeral spectacle of the market and fashion for tobacco, to its transiency, in the vein of the seventeenth-century vanitas still-life genre of painting: ‘Smoke is now a good. The world and these times sell nothing but smoke and vanity’.

Fashionable Young Men

Next a strapping young man in sword and spurs, legs akimbo, puffs away on a long pipe, much to the disgruntlement of the three women behind him. One woman holds a pipe whilst appearing to be sick from imbibing tobacco. The verse proclaims that ‘the German man praises the new drunkenness/that so suits the beer tankard’, but the author suggests that, unlike beer, the newfangled means of intoxication is part of a new and youthful culture of conspicuous consumption and social aspiration; tobacco as a marker of social status. The ‘sneering idiot’ in the picture ‘smokes about the house/and thinks/this makes him a good monsieur’. To top it off, tobacco smoke is a pestilence in the home; whilst his mother ‘grumbles’, the smoke ‘drives almost all of them out of the room’.

Penniless Smokers

Image D turns its attention to tobacco use amongst the poor. In contrast to the well-to-do gentleman in the previous image, here we see a down-at-heel shoeless vagrant in tattered trousers and an unfastened bodice, the swag containing all his worldly goods flung carelessly onto the ground whilst he leans on his make-do walking stick to puff on his pipe. Despite his poverty, this ‘poor sod… sticks this herb in his empty pocket. If he has nothing else/then he has tobacco’, for tobacco is not ‘proud’ but ‘full of pity’ and ‘one finds it by the rich/just as by the poor’. Why, the author asks, does the poor man not repair his trousers rather than buy tobacco? ‘Tobacco helps for hunger’ is the response. The message here: whereas the rich smoke in order to enhance their social standing, the poor are slaves to necessity. The storks nesting on the chimney of the less-than-modest dwelling in the background suggest a sympathy with the poor – here this ‘poor wretch’ – for the snake-eating stork was a symbol of goodness. Historians working on the material culture of tobacco have noted, however, that even the poor were in tune with fashion when it came to tobacco paraphernalia such as tobacco boxes and pipes, albeit within their financial means, suggesting that tobacco also had a social purpose for them.

Trouble and Strife

Vignette E takes us indoors into the living room of a well-to-do household. A candle burning brightly on the table tells us that it is night and indeed the next satirical blow falls on nocturnal activities: ‘This herb never lets anyone die of hunger. Yet the women suffer from starvation/Tobacco prevents them from earning the dessert’. Tobacco here is a scourge of marital relations. In the picture two women stand at the table, one gesticulating wildly and pointing at her husband, who has fallen asleep at the table, upon which his pipe and length of tobacco lie. Her friend stands beside her, listening to her woes: ‘Oh, my husband, he drinks so much of this rubbish/that afterwards/he is unable to/you know what. He sleeps at night and does naught but wheeze’. The placement of the tobacco and pipe between husband and wife and the otherwise barren table are symbols sexual distance between the couple, a clear violation of the prevailing expectation in early modern (Lutheran) Germany that both husband and wife were entitled to sex within marriage for the purposes of procreation. Even when intimacy takes place, the lingering tobacco smell ensures revulsion on the part of the wife: ‘When he kisses me/his mouth stinks like a chimney. To the devil with this drinking’. Given the primacy of the household unit and the celebration of the husband-and-wife team in early modern German Lutheranism, this critique of tobacco positioned ‘the little herb’ as ruinous to the very backbone of society: the family.

Getting Above One’s Station

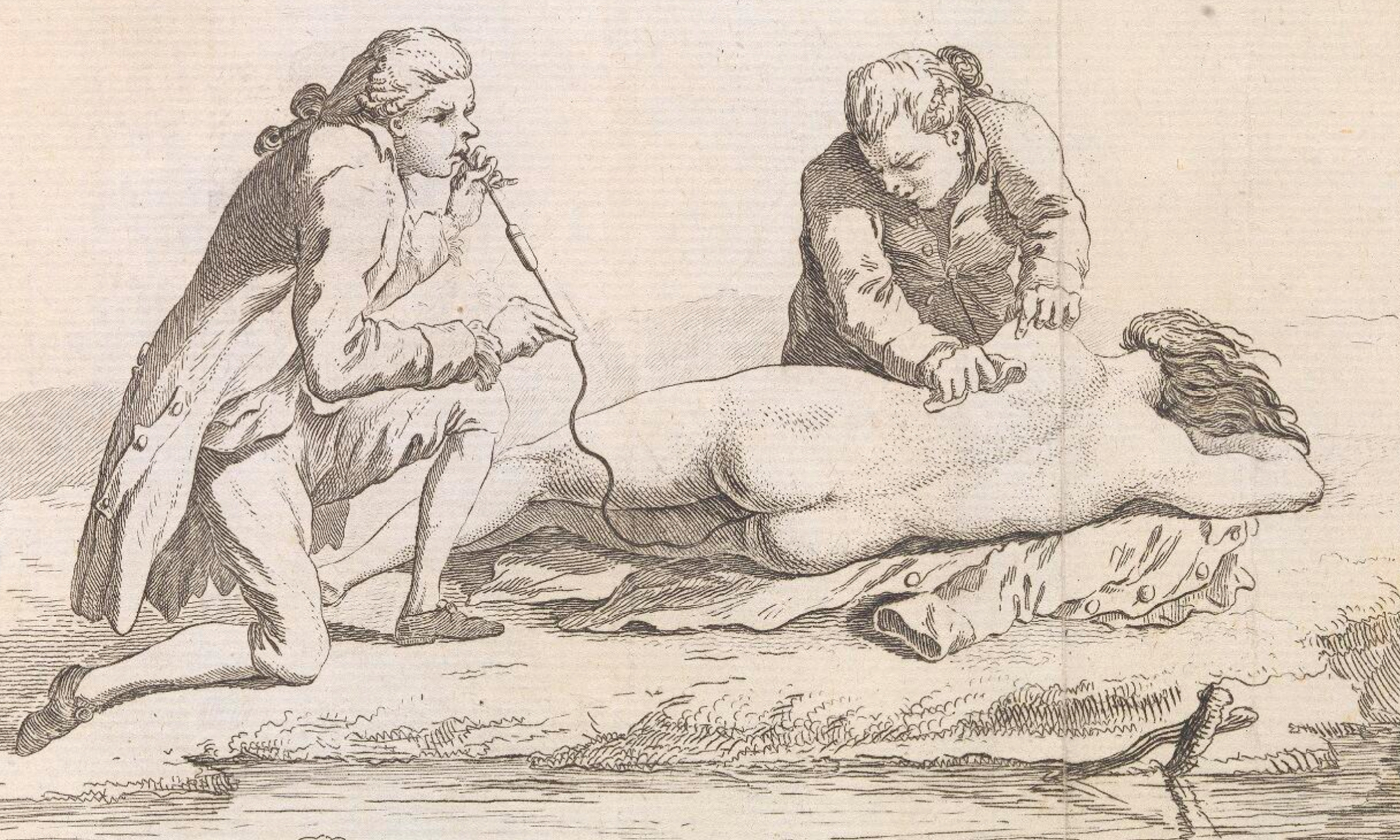

Next, two men armed with a bayonet, rifle, and sword, immediately recognizable to contemporaries as Landsknechte (common foot soldiers) through their costume. One smokes a pipe, whilst his companion appears to be speaking (perhaps regaling a heroic war story?). The verse begins by claiming that ‘Some often wish/that he were drowned and quickly suffocated/who first drank smoke/and he who brought this herb across the sea’. But it then provides a counter-perspective from the lower echelons of the military hierarchy: ‘The foot soldier wants not/that this come true’, for tobacco helps him pass many a long hour waiting for the enemy and he uses the ash from his pipe to heal his horse’s wounds. This juxtaposition between the ‘they’ and the foot soldiers suggests once again a division between poor and rich revolving around the politics of the consumption of luxury goods: Who is allowed to consume what? What kinds of consumption are appropriate to a particular social station? In early modern German society sumptuary laws dictating the clothing and goods that could be consumed by the various social stations prescribed consumption. Although tobacco was originally introduced to Europe by simple sailors, the broadside suggests that consumption across the social stations meant that tobacco caused social confusion. In the last part of the verse, it is the Thirty Years War that has sown this social turmoil. Like the bored foot soldiers, the landless farmer has perforce acquired skills and practices beyond his station:

What does war not bring to countries?

The farmer/ whilst it costs him his field/

Has thus learnt French/ Welsh/ Latin;

the German tongue has rusted up in his mouth.

Cantoning (soldiers) has been of no use/

Other than teaching him to master smoke in his mouth.

And tobacco also catapulted the peasant beyond the parochial and into the ‘global’, for learning to smoke is to partake in a cultural practice brought to Europe by the merchant ships of colonial globalisation and spread into every crevice of the Old World via a pan-European war.

Women and Trousers

Vignette G is all about gender relations. Two well-dressed men and a woman sit together at a table. Then men look on as the woman smokes a pipe. On the table lie the familiar utensils: another pipe, lengths of tobacco, and a knife. The verse begins with a quip that ‘The woman thinks no less of herself/ than the man’. Hence she seeks to ‘grab… the scepter’ – a key symbol of imperial and princely power – out of the man’s hands. The metaphor of the scepter for the pipe draws a satirical connection between the domestic space and the sphere of public governance to highlight how ridiculous and improper it was for women to smoke. Deploying the well-known trope of the ‘battle for the breeches’ to relate the gender topsy-turvy caused by tobacco, the author chides: ‘I believe it true/it will not be long/and they will wear trousers’. The woman sits down opposite the man and ‘smokes with him for a wager’, a further example of unseemly behaviour. The final line of the verse a lewd play on sexual promiscuity, with the smoke a symbol of illicit sexual penetration and a defilation of the proper sexual order:

The noble smoke creeps around her gentle body/and arrives thus often at secret places.

It enters into her/that does not exit these places/you well know what; I fall silent.

Men Without Measure

The finale is an ode to tobacco’s essential goodness, upon which people ‘bring dishonor’. Two men bringing up smoke – one onto the ground, the other out of the window – with pipes in hand display the fruits of this abuse:

You are becoming too common. That is praise for you/you can well concede: goodness does not offer itself to one person alone.

If one uses you ill; it is the way with all things. Abuse cannot turn something good into something evil.

And here is the moral conclusion: human behaviour, not the ‘noble herb’, is what turns the world inside-out and upside-down, into a world where physicians become wandering salesmen, honourable women are driven out of the domestic sphere, other less honourable women make a grab for power, and all the world – regardless of station, nation, or wealth – is bound together by a common practice: tobacco smoking.

Used with measure; it will make pure your brain, the fatherland of wit.

The phlegm exits/ where this smoke enters.

If it creeps into the body/ the back forehead sweats/ so the smoke awakens (it) from below and above.

Here the author alludes to tobacco as something that both purifies the body and enhances and awakens the senses. Scholarly medical opinion in the seventeenth century generally sketched tobacco in a positive light, highlighting the pharmacological benefits as a purgative, diuretic, and sweat-inducing substance that fitted perfectly with the prevailing concept of the body’s four humours that required constant regulation through such mechanisms. And tobacco found its way into many traditional modes of healing: compresses of tobacco leaves to treat wounds, tobacco juice helped cure pains and rashes, and tobacco pills were a well-known cure for toothache. Yet not everyone agreed, and debate on the salubriousness and of the herb commenced as soon as it hit Europe’s shores, most famously politicised in James I of England’s Counterblaste to Tobacco (1604).

In the mid-seventeenth century, tobacco was a contentious good, but less because people thought it bad for your health. The danger was rather a moral and social one. As a close reading of this satirical broadside suggests, tobacco’s ‘power and effect’ was its potential – if used excessively or improperly – for rupturing social norms and relations and, quite literally, turning the world on its head.

Further Reading

- D. Ellmers, ‘Tabakdosen für Seefahrer. Hollands auf Zielgruppen ausgerichtetes Verpackungsdesign im 18. Jahrhundert’, Deutsches Schiffahrtsarchiv 34 (2012): 7–33.

- J. Goodman, Tobacco in History: The Cultures of Dependence (Routledge, 1993)

- W. Harms (ed.), Deutsche Illustrierte Flubblätter des 16. Und 17. Jahrhunderts, Vol. 1, Die Sammlung der Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel Teil 1 (Tübingen, 1985).

- A. McShane, ‘The New World of Tobacco’, History Today (April, 2017): 41–7.

- A. Menninger, ‘Tabak, Kaffee, Tee und Schokolade in Wissenskulturen der Frühen Neuzeit’, zeitenblicke 8 (2009): 3.

- H. Wunder, ‘He is the Sun, she is the Moon’: Women in Early Modern Germany (Cambridge, Mass, 1998 [trans. T. Dunlap]).

[1] Petum (Ger.) and petun (Eng.) are now archaic forms of the French word for the tobacco plant or a preparation of tobacco leaves. In early writings on tobacco ‘petun’ was described as the indigenous name for tobacco.