Intoxicating substances are part of everyday life, especially during social interactions. At the same time, pressure on space in urban regions and cities is great; not only today, but also in the past. How do cities and urban populations past and present accommodate drug consumption and negotiate public space use? Whose voices are heard when it comes to policymaking about public space and substance use? Moreover, what happens when you bring historians, criminologists, political scientists, anthropologists, and practitioners from drug work together to discuss these questions? Back in October we gave it a try and invited experts from different backgrounds to join in a horizon-widening discussion based upon the fast-talk method, a focused and time-limited discussion designed to generate policy-relevant information.

In preparation for the digital event, all experts took part in a two-phase written consultation. They shared concrete examples from their research or professional work with the other participants and reflected on similarities, differences, and points of tension. The examples and methodological as well as theoretical reflections generated during this consultation process formed the basis of our online discussion. Here is a run-down of some of the main issues that arose in our discussion.

Recreation or Addiction? Different Perspectives on Drug Use

The way substance use is talked about and perceived varies depending on the space, time, and type of drugs that are consumed. But the social classification of users also plays a role, as does the classification of intoxicant use into something harmful or something enjoyable.

Street-based social worker Florian Pittner from Palette in Hamburg speaks of drug use as a disease (download full response [pdf]). Hayley Murray, on the other hand, an anthropologist from Amsterdam who does research on festivals and raves, classifies the use of drugs as recreational, and speaks of ‘pleasure’ and what happens when we grant young people who use drugs the autonomy to enjoy responsibly and take care of themselves and their peers (download full response [pdf]). Pittner is of the opinion that the type of drugs consumed often already indicates whether consumption takes place as part of an illness or as part of recreation. He also sees a difference in age: while young people mainly use drugs as a recreational activity, older users have often been addicted for many years and suffer from related ill-health. They agree, however, that only the privileged bodies of privileged people are able to use drugs for pleasure.

In Berlin, however, this thesis of privilege does not always hold as even ostensibly privileged, non-addicted consumers struggle with major (health) problems. In the Berlin party scene, for example, mental health and discrimination are significant challenges.

The Space is Not Problematic; It is Made Problematic

Johan Edman, a criminologist at Stockholm University, argues that the categories of age, gender, and class translate into space. It is thus not the space itself that is problematic; rather, the space becomes problematic because of the social status of the people occupying it. He provides the example of housewives in Sweden who used amphetamines until the 1960s, which was widely known and perceived as largely unproblematic. Only when the younger generation discovered the same drugs for themselves on the 1960s party scene did the consumption of uppers become a point of public debate. Thus the age category shaped the space in which these drugs were consumed as well as the debates surrounding use.

Gabrielle Robilliard from the Intoxicating Spaces project agrees that it is not necessarily the space itself that becomes problematic, but rather social mechanisms creating connotations that make a space problematic (download full response [pdf]). A park, for example, may be used by young people to take drugs because they are being pushed (for whatever reason) into the public sphere. This particular space then becomes associated with that age group and that kind of drug use, rendering it a problematic space. Ton Nabben, a criminologist at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, makes a similar point in relation to Amsterdam coffeeshops, where overcrowding resulting from increased tourism has displaced cannabis consumption into surrounding areas in what he terms a ‘waterbed effect’ (download full response [pdf]).

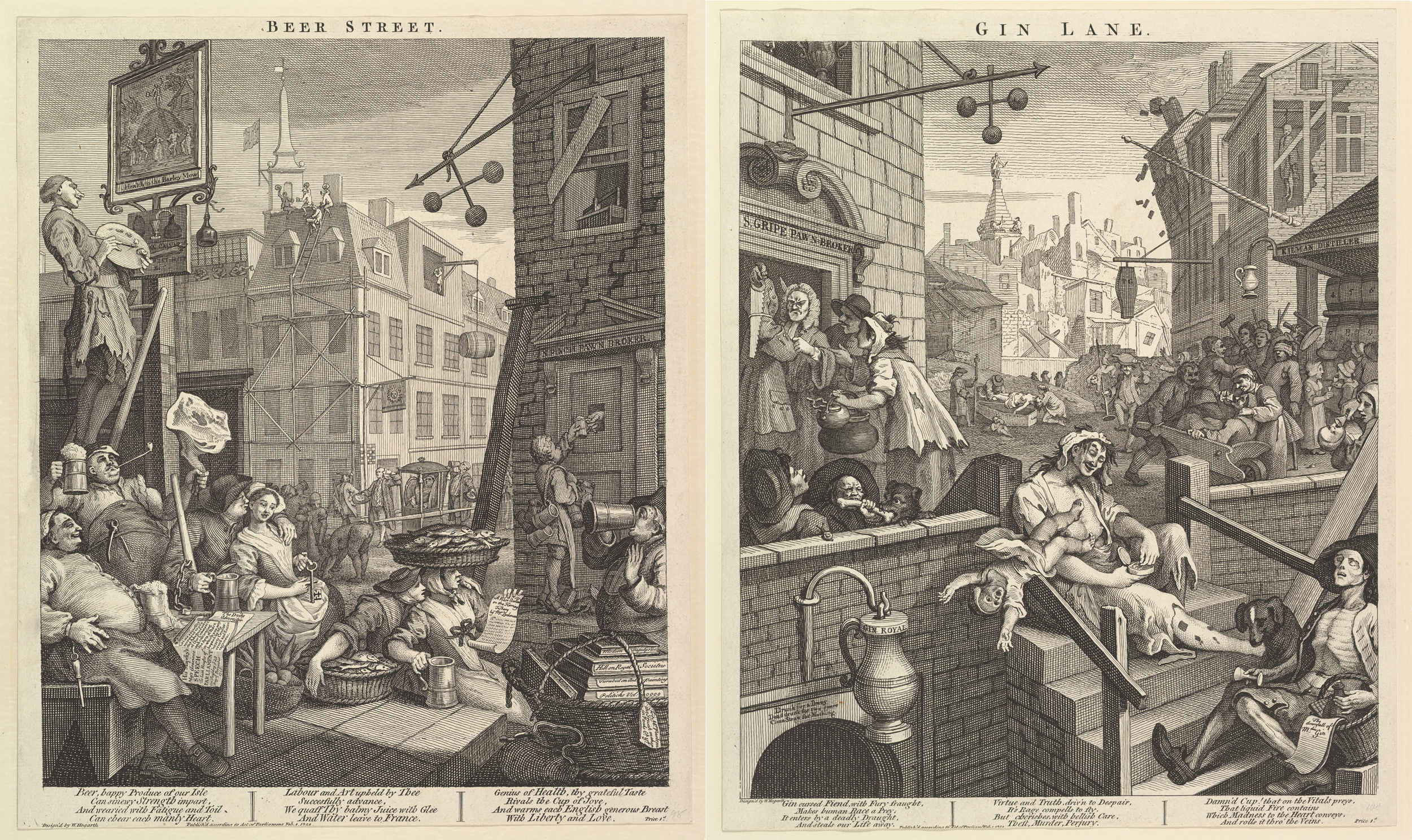

Edman introduces the example of William Hogath’s Beer Street and Gin Lane from 1751. In Beer Street, middle class people drink beer and enjoy it in a civilised way, while in Gin Lane, poor people drink gin, which leads to a loss of control and violence. The artwork contributed to the enforcement of the Gin Acts, which made gin more expensive and was intended to make the lower orders drink less alcohol (in particular less gin). This kind of propaganda drew strong associations between space (here the street) and the social status of the consumers and their intoxicant, which made the space either serene and civilised or disorderly and problematic.

Pittner adds a contemporary example: alcohol consumers cause less complaints and attract less attention in his district in Hamburg than crack addicts, even if they behave exactly the same way in exactly the same place. The space becomes a problem (to varying degrees, or not at all) depending on the drugs used and the kinds of associations and responses those substances evoke.

Thus both historically and today, some areas of the city are associated with certain kinds of intoxication practices. The meanings a society accords to its spaces (either generic or specific) are influenced by the kinds of drug consumed in them as well as the social status, age, and gender of consumers.

The Concept of Safety as an Individual Construct

One strong argument (but not necessarily the main reason) made for liberalising Sweden’s alcohol policy was safety, Edman explains. Consumption was supposed to be brought out of the private sphere into public spaces. That is why, since the 1990s, clubs and restaurants can stay open until five in the morning to encourage people to stay whilst consuming. In the case of excessive or harmful drug consumption, users are not alone and help is close to hand. Moreover, intoxication seems to be easier to control in public. This political concept of safety leads to harm reduction measures.

Yet the definition of ‘safety’ is different depending on the individual’s position. The same situation may seem dangerous or safe depending who is watching; someone consuming drugs might create a ‘safe’ space for other substance users by creating an environment in which they are neither stigmatised nor judged. But this very space may seem dangerous for non-consumers of those drugs. In the festival scene, a ‘safe’ space often means that substance users are safe to continue partying without being judged or discriminated against.

Another concept of ‘safety’ arises in Berlin; parts of the Berlin club scene have declared themselves ‘safer’ spaces by virtue of increasing awareness of discriminatory and especially sexist behaviour. The basic idea of ‘safer’ spaces for some clubs and party collectives also includes acceptance of drug use as a form of behaviour otherwise considered ‘deviant’ from the perspective of wider society.

Everyone has a need for safety. But the different concepts of security are individual and often contradictory. Whilst for some people a private space is synonymous with safety, others need the public sphere to be able to consume safely. What people perceive as ‘safe’ may also change over their lifetimes and also according to their life circumstances.

To make drug taking something less ‘deviant’, the concept of safety is important. When intoxication appears to be managed, it might be less frightening to non-consumers sharing that space. Pittner mentions the use of public infrastructure in Hamburg. Clean-ups, gardening initiatives and music can make places more pleasant for everyone and lessen the fear. Robilliard suggests that the notion of safety might be based more on emotions and feelings than on factual evidence. Therefore, what is perhaps really at stake (i.e. influential) is whether people feel safe.

What Triggers a Change in Policy-Making?

Sometimes intoxication can even become part of a city’s cultural heritage. After German reunification, the wastelands of Berlin were taken over by younger people and drugs became an important aspect of this space use. This shaped the image of Berlin as a city known for its nightlife, open-mindedness, and cutting-edge modernity. That intoxication and the party scene became part of the cultural heritage of Berlin and led to a positive outcome, including more concepts of harm reduction, safer sex, etc. Here, intoxication was aligned strongly with recreation and was conferred a purpose (however hedonistic).

But who is actually capable of influencing policy-making? Age, gender, and class also impact how and if a person or group is heard. As a result, notions of safety as conceived by certain groups may have little influence on policy-making, because these groups are either not heard or not listened to. This can become problematic, for it means that public and health policy (in both past and present) may reflect and potentially reinforce pre-formed attitudes to particular drugs, drug practices, and their consumers, leaving little ‘space’ for variant understandings of and motivations for drug consumption amongst users.

Given that most people in most societies consume intoxicants in one form or another – from caffeine to cocaine – we need to seriously question why we demonise certain types of consumption and accept or even valorise others. Looking at concrete contestations and negotiations over space can help us to better understand the social and cultural mechanisms behind these associations.