While it suffers from the vicissitudes of plague and war, Stockholm grows in our period from a tiny harbour to a vibrant political and economic centre, crowded by international people and commodities.

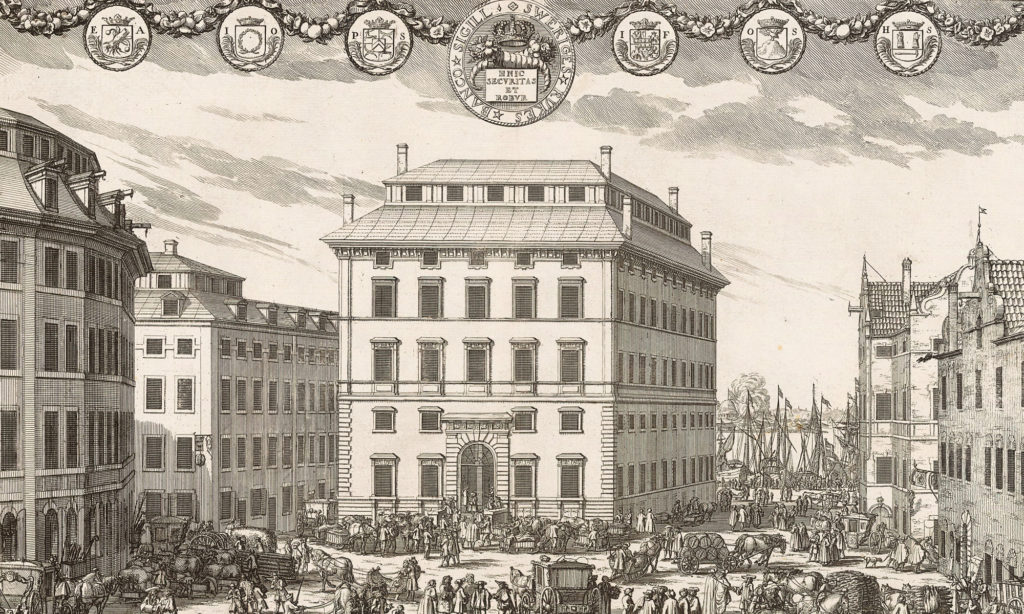

Featured Image

Stockholm depicted on a mid-eighteenth-century map. Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg (CC BY-SA 4.0)

A Commercial Metropolis

- At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Stockholm, with its population of about 9,000, is by far the biggest Swedish city. In comparison with London, Amsterdam, Hamburg or even the Danish capital, Copenhagen, however, it is a small town. Its residents number 60,000 by the mid-1700s, and 93,000 by 1850.

- In the course of the Thirty Years’ War, Stockholm grows rapidly, and by the mid-seventeenth century, it already hosts about 35,000 inhabitants. This exceptionally fast population growth is an effect of Stockholm’s role as the capital of a new European Great Power. The city represents the honour of the realm, its decoration and beautification considered a direct reflection of Sweden’s new status after the Treaty of Westphalia.

- The city’s expansion is even more remarkable if we consider that the mortality rate was considerably higher than the birth rate: apart from the increasing population, the circulation of people through the city was vastly larger.

- The inflow of old and new noble families connected to the royal court and the administration as well as foreign diplomats, military officers, artists, and scholars, attracts a large number of merchants, craftsmen, and servants, visibly changing the face of the city and constantly replacing the people in it.

- There was significant immigration of German and Dutch merchants who sought to take advantage of the burgeoning city. German immigration to Stockholm had played an important role since the Middle Ages. Trade connections, Stockholm’s municipal legislation, even the Swedish language witness a strong German influence in the urban environment. Dutch immigration was a more recent phenomenon. In the period 1621-1648 participation on the Protestant side in the Thirty Years’ War entailed rise of Dutch economic influence in Sweden, with the inflow of capital, know-how, and people.

- Stockholm grows as the commercial centre of the Swedish kingdom. This is a natural outcome of its location – situated in the middle of the expanding Swedish Baltic empire, on the crossroads of waterways between east and west, and between north and south. But Stockholm’s role as Sweden’s commercial metropolis is also an outcome of the conscious mercantilist policy of the state. Royal legislation prohibited exports from northern Sweden (all towns north off Stockholm). Thus, almost all exports of iron and copper, Sweden’s major export products, were channeled through the capital. As Sweden’s major market for consumer goods, Stockholm also dominated imports. In the seventeenth century about two thirds (60–70%) of Sweden’s foreign trade, both exports and imports, were channeled via Stockholm. The second most important Swedish town in this period – Gothenburg – accounted for about 10% of the kingdom’s trade .

The City on the Islands

- Stockholm is a city on islands. The medieval town was situated on the island that is called Gamla stan (Old town) today. Squeezed together were all of the realm’s important institutions, the royal palace, state bureaucracy, as well as municipal buildings. This also signified the Crown’s increasing influence over municipal matters. By the early seventeenth century, suburbs were well established both to the north and south of the central island. The northern suburb of Norrmalm was most fashionable, especially after the realigning of the city’s streets in straight lines along Renaissance ideals. The labouring poor were most common in parts of Kungsholmen in the north, and Södermalm in the south.

- The eastern-oriented bank of Gamla stan was the major quay for deep-water vessels. It was also the location of the most splendid houses of the city’s mercantile elite – the Crown, wanting to dazzle foreign visitors, gave away plots along the quay on the condition that a stone building was erected on the site. Later on, the inhabitants were referred to as the ‘quayside nobility’ (skeppsbroadeln). From here, vessels loaded with Swedish exports, iron, copper, tar, pitch, and planks sailed to western Europe. The western-oriented seaside harboured vessels trafficking the great lake of Mälaren, connecting Stockholm with Sweden’s interior.

A Stagnating Metropolis or the Kingdom’s Political Heart?

- Two decades of war (1700–21) sapped the city of its menfolk; to add to the miseries, the plague hit in 1710, killing at least a third of the population. Between 1713 and 1714 Russian troops occupied Finland bringing scores of refugees to the Swedish part of the realm, 12,000 of whom came to Stockholm. At the beginning of the 1720s the population just reached 40,000 again. The realm had contracted almost completely into what is modern day Sweden and Finland. Not until the mid-eighteenth century did the city regain its footing, with a new royal palace in place.

- Like all preindustrial cities, Stockholm depended on a steady arrival of immigrants in order not to decline, as mortality was very high. With the beginning of the Great Northern War in 1700, expansion ended. It was as if the fire that destroyed the royal palace in 1697 heralded a new time for the city: an end to extravagance, and a shift in power in the Baltic from Stockholm to St Petersburg. Crown and city resources were directed towards the war, and the nobility had lost many of their properties since the Crown had carried through a program of reclaiming previous donations in order to shore up state finances.

- Eighteenth-century Stockholm has been described as ‘a stagnating metropolis’. Yet, such a view misses the thriving political life of the city and its economic revival. The so-called Age of Liberty (1719–72) was characterised by a remarkable political experiment. The political power shifted from the King to the Diet (Riksdag) consisting of four estates, including the estate of free peasants. With Diet sessions regularly taking place in the capital, Stockholm turned into the vibrant political heart of the kingdom. Politics took place in the Diet but also in pubs, wine shops, coffee houses, private homes, and in the streets. In 1728, there were already fifteen coffee houses in Stockholm. Deputies from the countryside learned of new exotic goods and dispersed new consumer habits across the kingdom.

- Eighteenth-century Sweden continued with its conscious mercantilist policy. It promoted export trade, especially in iron, but it also introduced new shipping regulations inspired by the English Navigation Acts. Shipping under the Swedish flag grew and Stockholm became the home of about a half of Sweden’s registered tonnage.

- As the kingdom’s commercial metropolis and the home of its mercantile elite Stockholm gained most from these policies, and by mid-century its ‘quayside nobility’ reached the highest point of its wealth and influence. Political struggles in the 1760s changed the situation. The city’s mercantile elite weakened, and the capital’s political benefits were partially removed. In 1772, the king Gustav III conducted the coup d’état that ended the Age of Liberty and established absolutism. The King made deliberate attempts to curb political life in the city. Diet meetings were moved elsewhere, and the newly established police monitored conversations in wine shops and coffee houses. Despite this, the city was at the center of opposition to the King. The book shops traded in subversive works from all over Europe.

- Sweden’s economic policy was shaped by traditional mercantilist ideas, in that exports were promoted and imports were kept to a minimum. This meant that the domestic trade in colonial and tropical products – including intoxicants such as sugar, coffee, and tobacco – was regulated and sometimes prohibited. Sweden’s sumptuary legislation on coffee is the best-known example of such laws, with its numerous prohibitions of coffee consumption (1756–61, 1766–69, 1794–96, 1799–1802, 1817–22). Despite the prohibitions, however, coffee was consumed in ever greater quantities, as were other goods regulated under sumptuary law. Smuggling of prohibited goods was also extensive.

- In contrast to the Dutch Republic and Britain, Sweden had no colonial empire, in spite of attempts to acquire one. The Swedish East Indian Company (1731–1813) traded almost exclusively with Canton in China, importing Chinese tea, silks, and porcelain, but most of the Chinese goods were reexported. The small Swedish Caribbean island – St Barthelemy – was acquired from France as late as 1784 and it did not produce any coffee or sugar. Sweden imported most of its colonial goods from France, Denmark, the Dutch Republic, and Britain.

- As imports of new intoxicants were perceived as harmful for the balance of trade the state encouraged the use of domestic surrogates, and the introduction of tropical plants in Sweden. Experimentation in producing Swedish wine, silk, tea, and other colonial goods was rife. But the introduction of tobacco became a great success. By the late eighteenth century domestically grown tobacco replaced most of the imports, and around Stockholm tobacco factories were significant employers of the lower echelons of the population. Coffee and sugar were harder to domesticate, and only with the introduction of sugar beet production in the late nineteenth century could tropical cane sugar be replaced.

Stockholm in the Nineteenth Century

- The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars were a highly disruptive period in Stockholm’s history. Politically, the absolute monarchy struggled to retain legitimacy as enlightenment debates on citizenship began to take hold. Absolutism was finally toppled in 1809, with a new King and new constitution that returned political power to the Riksdag.

- On the one hand, Sweden avoided most of the wars on the continent; and due to its neutrality even benefited economically. During the continental blockade, Sweden became a transit country in the trade with Atlantic sugar and coffee. On the other hand, in the war with Russia in 1808–9, which was a part of the Napoleonic Wars, Sweden lost Finland, representing a third of its territory, the greatest territorial loss in its history.

- The period after the Napoleonic Wars was marked by population growth and modernisation. Again, Stockholm was established in the new constitution of 1809 as the natural political centre of the kingdom. Economic growth meant more money to buy consumer goods, including tropical intoxicants. But growth also brought about greater social stratification and extreme poverty. One of the plagues of the time was binge drinking, and debates on how to prevent it were arguably the most significant issue of the time. Social movements, particularly revivalists, propagated for coffee and tea as alternatives to spirits leading to new social phenomena like ‘church coffee’ after Sunday services. Inspired by continental models, cake shops offered more sober, but sugar-packed, experiences.

- In the course of the first half of the century, Sweden became one of the great coffee-drinking nations. Today, the Swedes drink more than 8kg of coffee per capita and year, which makes them the sixth most prolific coffee-drinkers of the world.

Further Reading & Resources

- H. Hodacs, Silk and Tea in the North: Scandinavian Trade and the Market for Asian Goods in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Basingstoke, 2016).

- S. Lilja, Tjuvehål och stolta städer: urbaniseringens kronologi och geografi i Sverige (med Finland) ca 1570-tal till 1810-tal (Stockholm, 2000).

- L. Runefelt, Att hasta mot undergången: anspråk, flyktighet, förställning i debatten om konsumtion i Sverige 1730-1830 (Lund, 2015).

- A. Sandström, ‘Mellan Torneå och Amsterdam: en undersökning av Stockholms roll som förmedlare av varor i regional- och utrikeshandel 1600–1650’ (PhD thesis, Stockholm University, 1990).

- K. Sennefelt, Politikens hjärta: medborgarskap, manlighet och plats i frihetstidens Stockholm (Stockholm, 2011).

- J. Söderberg, U. Jonsson, & C. Persson (eds), Stagnating Metropolis: Economy and Demography in Stockholm, 1750–1850 (Stockholm, 1984).

- Stockholmskällan