It’s 1600 and Europe faces momentous change: the ongoing upheaval of confessionalisation, the colonisation of the New World, and the waning of medieval structures as trade routes and borders shift west from the Baltic region to the North Sea and the Atlantic. At the centre of these transformations is Hamburg, a thriving, self-governing centre of maritime trade on the Elbe River. With the Hanseatic League, the once mighty international medieval network of trading cities, now languishing, Hamburg keenly exploits the influx of exotic goods – in particular the new intoxicants – from the Americas, becoming one of the largest and most powerful international port cities in northern Europe.

Featured Image

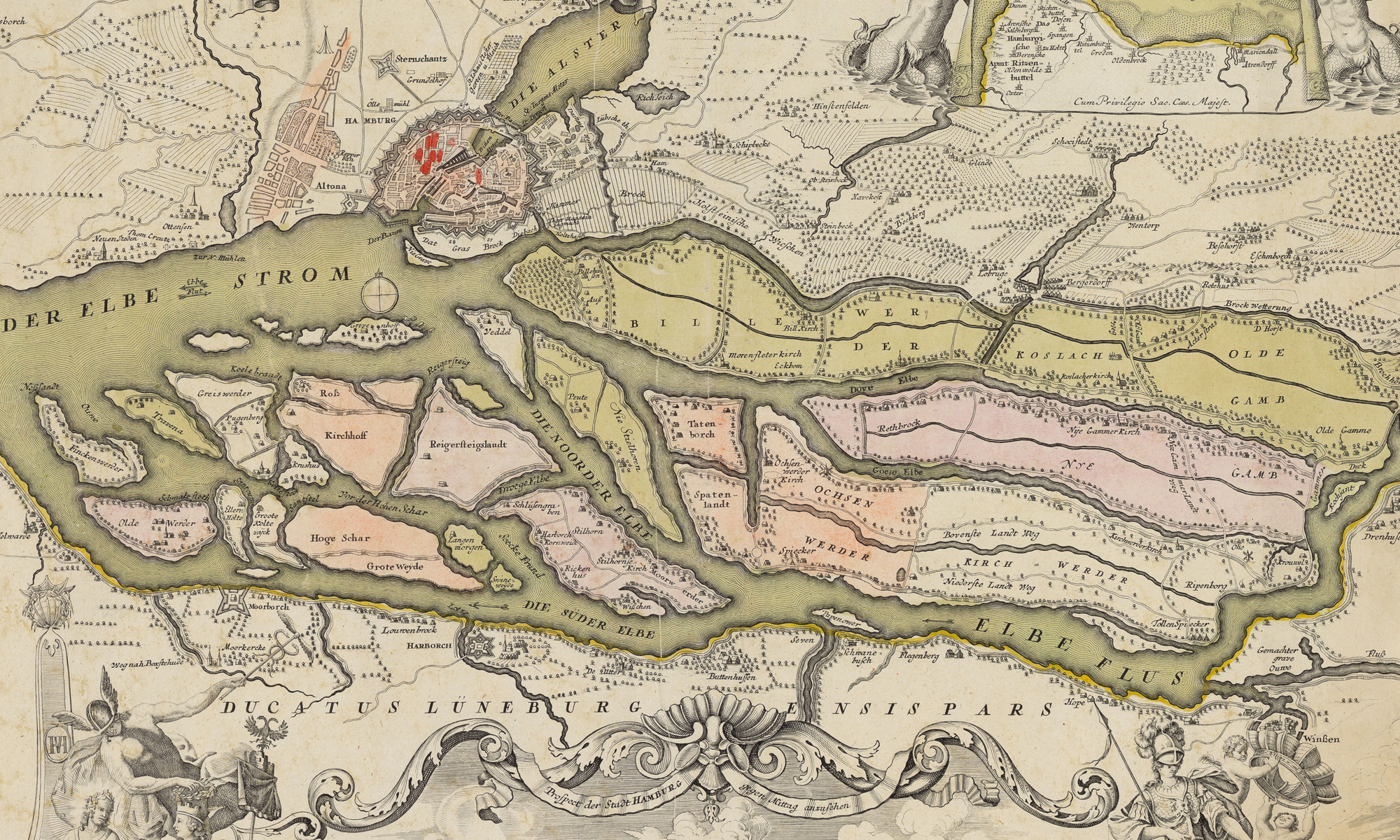

Hamburg, with its port, viewed from the Elbe river in 1730. Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg (CC BY-SA 4.0)

A Migrant City

- With around 36,000 inhabitants in 1600, Hamburg is the largest city in northern Germany. Over the next two centuries, the population grows rapidly and steadily so that by 1794 – on the eve of the French occupation under Napoleon – there are around 130,000 inhabitants.

- International diplomacy and massive municipal investment in almost impenetrable city fortifications in the early 1600s see off the worst of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), which ravages swathes of Germany. Yet the city is not immune to plague and other epidemic diseases, which exact a severe toll on cramped and dirty urban centres with poor sanitation such as Hamburg: in most years mortality (deaths) in the city outstrips fertility (births), and only around half of children born survive to the age of ten.

- So, like most early modern European cities, Hamburg depends upon immigration to sustain its population. The first major wave of newcomers to shape our period are Dutch, who from the 1580s seek refuge in Hamburg from persecution under Spanish rule. Although forced to convert to Lutheranism – the state religion in Hamburg and a precondition of burgher status – the Dutch newcomers from across the social spectrum soon make up a driving force in the Hamburg economy. Immigrants during the eighteenth century largely hail from neighbouring regions such as eastern Holstein, Mecklenburg, and Hanover.

- Like the Dutch, the Portuguese Jews bring their connections and manufacturing skills, enabling Hamburg to develop particularly strong trading relationships with ports offering direct access to the New World. The Rat (City Council) is keen for merchants with international networks or artisans with sought-after skills and knowledge to settle in the city and contribute to its prosperity. In 1611, for example, it permits the English Merchant Adventurers to establish an office in Hamburg to strengthen commercial ties with England.

Place and Space

- Water is early modern Hamburg’s defining geographical feature. Built on the junction of three rivers – the Elbe to the south, the Alster flowing north to south through the center of town, and the Bille to the east – it is a city of Fleete (canals) and bridges. Lining these Fleete are the Kontore (warehouses) of the merchants, who prize the direct water access to the port where the Alster River flows into the sprawling Elbe. From here, Hamburg’s merchants set sail upstream to Magdeburg, Dresden, and Eastern Europe, and downstream to the North Sea and the Atlantic coast. Hamburg presides over the stretch of Elbe between its mouth on the North Sea to the city and maintains the buoys securing the channels (since 1450). During the seventeenth century, the city spends vast sums of money on new and improved waterways, roads, paths, and institutions of vital importance to an international port city, such as the Hamburger Bank (1619).

- For most of our period, Hamburg is confined to a roughly 100-hectare area by its wall fortifications. Only in 1804 – the city is now bursting at the seams – does demolition of the wall begin, allowing the city to incorporate the settlements beyond the city gates. Hamburg has very little in the way of hinterland and rural territories; in the 1811 census, a population of 100,192 in the walled city and the extramural suburb of St Georg compares to just 31,805 in outlying villages. The devastating Great Fire of 1842, which destroys some 42 hectares of the city, has an unexpected silver lining: a new, modern city with wide thoroughfares and buildings of brick and stone to replace the dingy, narrow, and fire-prone slums of the Old City.

- New urban spaces for leisure and entertainment emerge en masse from the late seventeenth century and create new forms of sociability and cultural activity: oil lamps brighten the city’s dark streets from 1673, the Rat builds several new town squares, the city’s first opera house opens (1678), the wealthy establish exotic gardens for promenading, open-air theatre, and music, and the area in front of the Millerntor in the extramural parish of St Pauli transforms into a space of pleasure, entertainment, and vice. Hamburg is also home to one of Germany’s earliest coffeehouses (1677); by 1810, there are 32 across the city.

Governing the Merchant Republic

- In 1618 the German Kaiser confers the status of free Imperial city: Hamburg is now subject only to the Kaiser and is otherwise politically and economically independent.

- Hamburg is governed not by a dynastic urban patriciate or an absolutist ruler but instead by its burghers. Like Amsterdam, Hamburg thinks of itself as a ‘merchant republic’, i.e. a city governed and administered by its burghers in which merchants and mercantile values form the basis of republicanism. Of course, participation in the political life of this republic is greatly restricted by gender, religion, and status, for to become a burgher of Hamburg, one must be male, Lutheran, and own property in the city. In the seventeenth century, 15–20% of the population are burghers; by 1759, only around 10%. And the rest? Some 70–80% of the population is situated within the ‘burgher nexus’, as direct family of a head of household with burgher status.

- Political offices are largely voluntary. The most powerful executive body in the city, responsible for most political decision-making, is the Rat (the Senate or city council), consisting of members of the urban elite (largely lawyers and merchants). The other executive body is the Bürgerschaft (Citizen’s Assembly), which comprises all burghers in Hamburg and convenes twice a year to vote on new or amended laws put forward by the Rat. Dissatisfaction over the distribution of sovereignty between the Rat and the Bürgerschaft sparks the creation of Hamburg’s ‘fundamental law’, which endures to the mid-nineteenth century.

- In the seventeenth century Hamburg consists of five parishes: the older St Petri, St Nikolai, St Catharinen, St Jakobi parishes and, from 1647, the ‘poorhouse’ of the city, the parish of St Michaelis. The parishes are the centre of the city’s religious, social, and political life. They select deacons to administer the Gotteskasten (God’s Chest), which funds alms as well as civic institutions and offices. Deacons from all parishes convene in a collegial body known as the Forty-Eight, which also advises the Rat on matters of prosperity and public order. The three eldest members from each parish in the Forty-Eight also sit in the Oberalten (Aldermen), the collegial body responsible for upholding the constitution.

- When Napoleon’s troops march into Hamburg in 1806, life as the city knows it ceases. The French dissolve the Rat and the city’s republican constitution and introduce the Napoleonic Code. This brings sorely needed administrative modernisation, although due to the blockade of the Elbe Hamburg’s commerce is in tatters and its physical and economic recovery is slow. After the French leave in 1814, Hamburg embarks on a restoration of former political arrangements. Ever louder calls for reform from the increasingly confident urban burghers are stymied by more powerful conservative elements until the revolution of 1848 forces Hamburg to adopt a new constitution and a (slightly) more representative and inclusive form of government.

A Colonial Economy

- In 1668 Denmark declares Altona – a town on the Elbe a stone’s throw away – a city and establishes Europe’s first free port to compete with Hamburg. Altona flourishes, not least because its religious tolerance attracts merchants from all over Europe (only in 1785 does Hamburg permit religious freedom). Until Denmark recognises Hamburg’s independence in 1768, the two cities stand side-by-side on the Elbe, vying for international and regional trade. Yet there is enough of that to go around and both cities profit greatly from the competition.

- Although Hamburg remains the major grain transhipping centre in northern Europe, the influx of colonial wares together with new international trade networks sounds the death knell for the city’s traditional industries (brewing, shipbuilding, and textiles). Sugar refining, tobacco manufacturing, and calico printing emerge in their place and assume supraregional importance until the Napoleonic occupation. These newer industries as well as many other sectors of growing importance in Hamburg (shipping and parts of the building industry) operate outside of the guilds (known as Ämter) and challenge the traditional form of guild-based economic organisation in the eighteenth century. Protoindustrialisation creates huge demand for semi- and unskilled labour and, with it, large numbers of labouring poor.

- By the mid-eighteenth century, domestic production and manufacturing for export are no longer the city’s economic mainstay as Hamburg fashions itself as a centre for transhipping. With this, the city depends increasingly upon international trade and its vagaries. In the 1780s and 1790s, Hamburg experiences an economic boom, with an average of 2,000 ships from across the world entering the port per annum: by 1789–91 its most important trading partners are France, England, Holland, Spain, Portugal, and the USA.

- Only in the first half of the nineteenth century does Hamburg begin trading directly with the New World, initially with the USA. As the Spanish colonies acquire independence, Hamburg refocuses its trade routes and relationships on Latin America. From the 1830s Hamburg’s merchants turn to West Africa, where they exchange industrial goods from Europe for raw materials (exotic woods, palm oil, rubber, coffee, cocoa, gold and ivory). They venture further into Southeast Asia in the 1840s, and Hamburg’s trade grows exponentially when China and Japan open up to European trade.

- Although it has no colonies of its own, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Hamburg is a fulcrum in a global colonial system and facilitates the movement of slave-produced goods deep into continental Europe. Its mercantile success thus provides the machinery for and perpetuates imperial oppression and exploitation.

Further Reading & Resources

- M. Gretzschel, Hamburg: Kleine Stadtgeschichte (3rd edn, Regensburg, 2016).

- History of the Port of Hamburg

- F. Kopitzsch, Grundzüge einer Sozialgeschichte der Aufklärung in Hamburg und Altona (2nd edn, Hamburg, 1990).

- M. Lindemann, Patriots and Paupers: Hamburg, 1712–1830 (Oxford & New York, 1990).

- M. Lindemann, The Merchant Republics: Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Hamburg, 1648–1790 (New York, 2015).

- J. Werner & H. Loose (eds) (1982), Hamburg: Geschichte der Stadt und ihrer Bewohner (Vol. I, Hamburg, 1982).