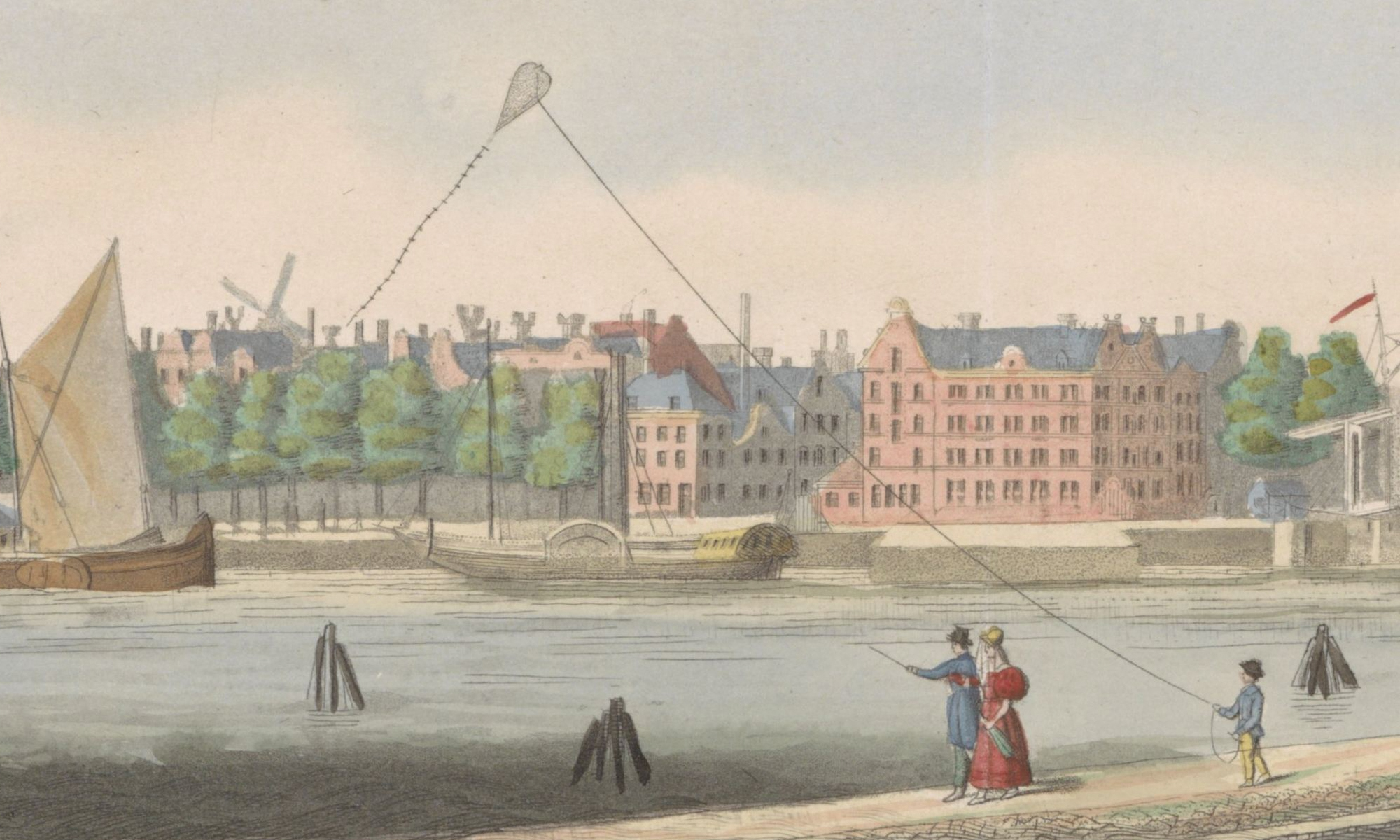

During our period Amsterdam consolidates its status as a global commercial centre and expands considerably beyond its medieval walls. By 1650 its population is estimated at 175,000, making it the third largest European city (after London and Paris), which it remains until the early nineteenth century. Amsterdam becomes a key port and hub of international trade; new multinational enterprises such as the Dutch East India Company (VOC) bring exotic and colonial goods to the city, from where they are distributed all over Europe. Foreign visitors and merchants arriving by ship are impressed by the long waterfront, and by the immense ‘forest’ of ship masts in the harbour. The city is flat, encompassed by a landscape of swampy lowlands and windmills, and full of waterways and greenery. It is also noisy with much traffic, no underground sewers, and an irregular water supply, while the poor quality of the water in the canals and the smoke of chimneys are an environmental nuisance. Relative economic and demographic decline takes place after 1740.

Featured Image

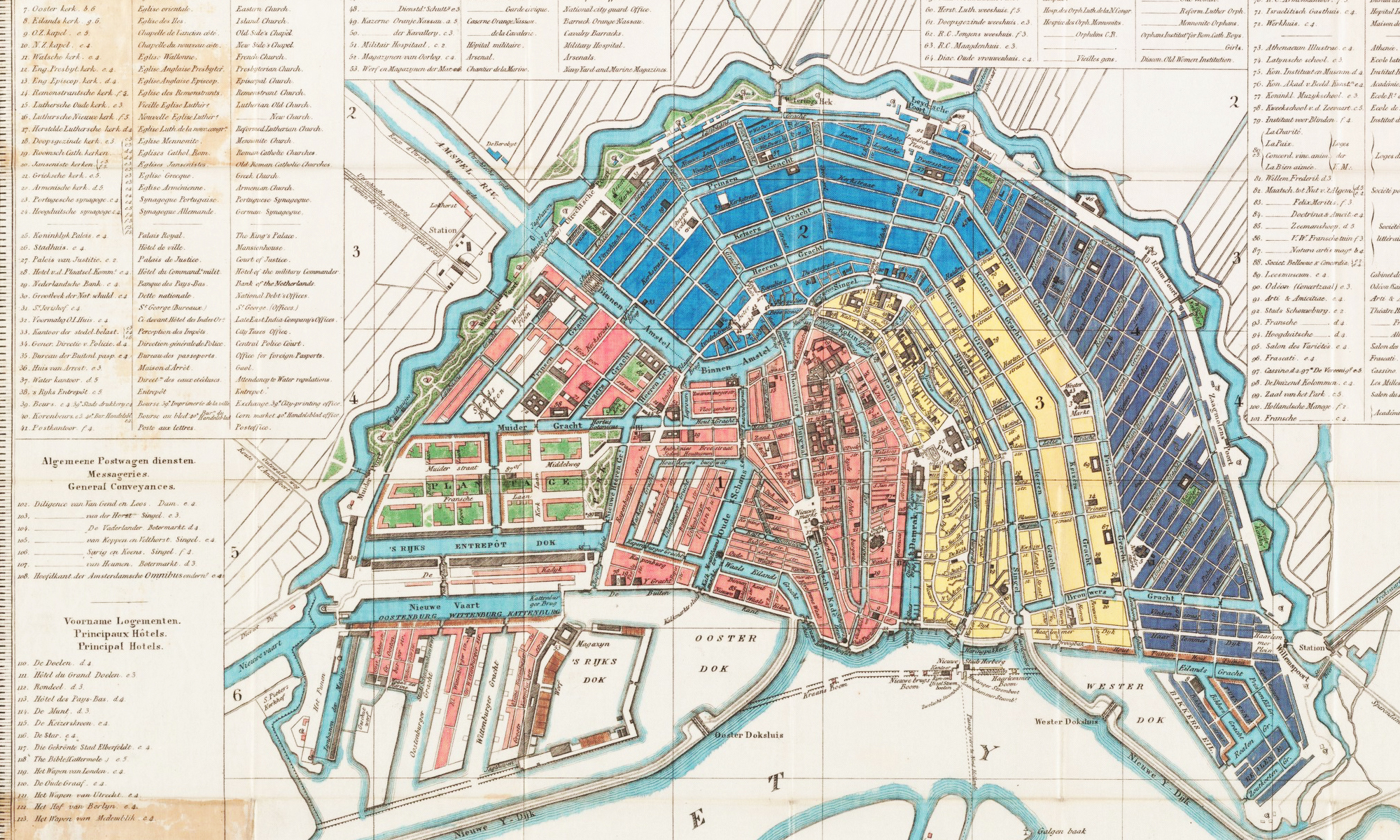

A map of Amsterdam in 1845. Harvard Map Collection

Demography

- Amsterdam’s population exploded during our period. Estimates are as follows: 1600: 54,000; 1622: 105,000; 1650: 175,000; 1680: 219,000; 1700: 235,000; 1725: 243,000; 1750: 234,000; 1760: 241,000; 1800: 203,000; 1815: 195,000; 1850: 224,000.

- Amsterdam is a migrant city. Population growth occurs because of the influx of newcomers, mostly from Germany, but also including Portuguese Jews and refugees from the Southern Netherlands during the Revolt against Spain, and later Scandinavians, Jews from Eastern Europe, and so on. Between 1600 and 1800, one in four people who get married in Amsterdam is originally from outside the Dutch Republic.

- Until 1835 mortality rates are higher than the number of births. Mortality decreases from around 60 per 1,000 in the first half of the seventeenth century to around 34.5 per 1,000 by 1850.

- Amsterdam is a city with more women than men.

Geography

- Amsterdam is built on peat-soil and protected against flooding from the sea by a dam in the centre of the town and by dikes.

- On the seaward side Amsterdam sits on a bay, the IJ, that connects the city to the Zuiderzee (Southern Sea) and from there to the North Sea.

- On the landward side Amsterdam is the centre of an urbanized country with good land connections by river and road to other major though much smaller Dutch cities (Leiden, Haarlem, Utrecht), and to West Germany and the Southern Netherlands (now Belgium).

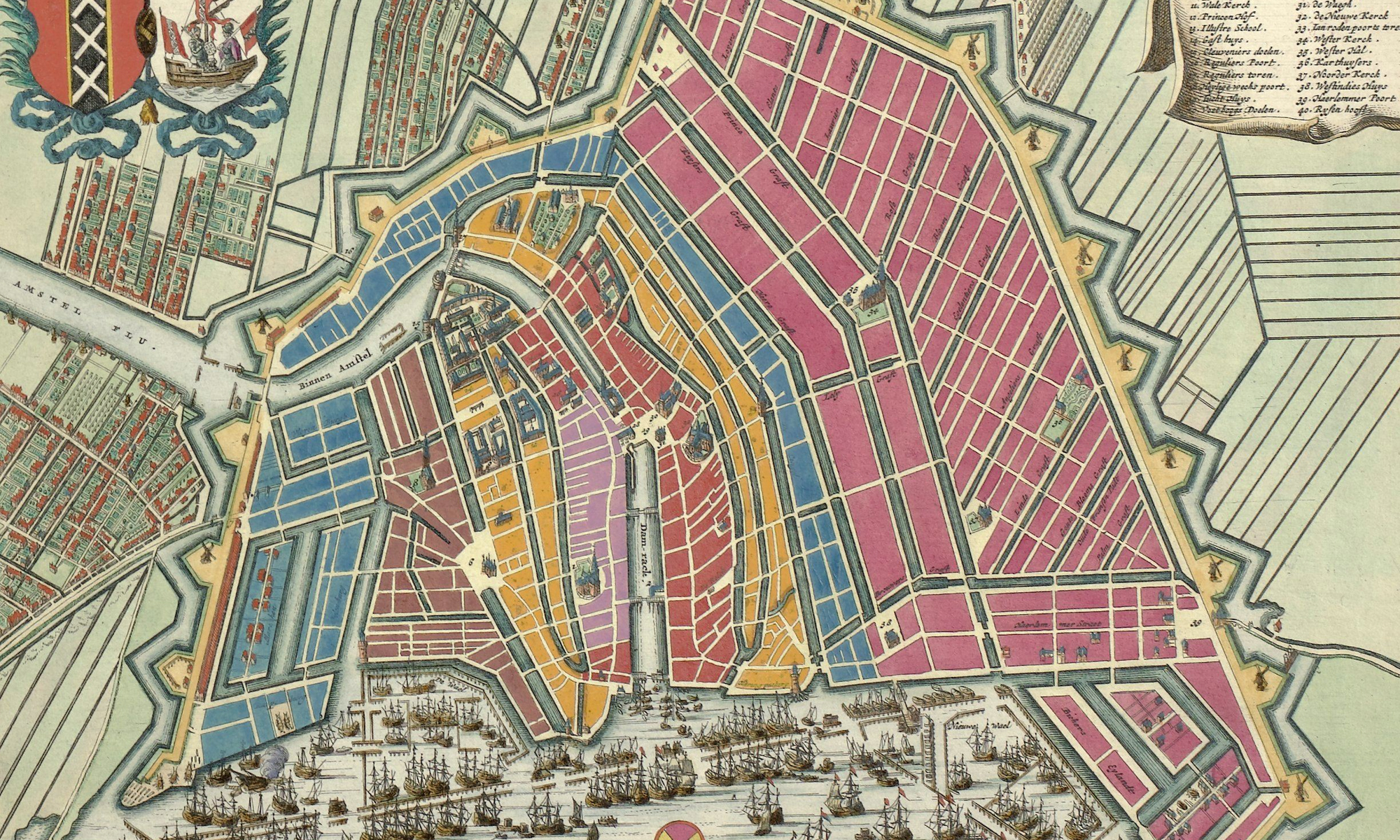

- Between the Protestant take-over of the city in 1578 and the 1660s Amsterdam expands fourfold beyond its fifteenth-century stone walls, establishing new city limits and developing the shape it has today.

- By 1662 Amsterdam’s medieval inner city is surrounded by the canal belt. Beyond this are the working-class neighbourhoods such as the Jordaan to the West and the Eastern Docklands to the East.

- The canals circling the inner city (Singel, Herengracht, Keizersgracht and Prinsengracht) house the wealthier citizens, especially on the west side. But they live in close proximity to artisans and shopkeepers in the intersecting streets.

- The final phase of the city’s expansion, creating new neighbourhoods and islands for housing and industry and enlarging the waterfront in the harbour, is completed by 1730. Until the second half of the nineteenth century there is now enough space within the new city walls to satisfy the needs of housing and industry.

- After the arrival of the first railroad connection in 1839 the difference between city and country becomes less absolute and the city walls are torn down.

Daily Life

- Amsterdam is a walled city, and until 1845 the gates are closed at night. The seventeenth century city wall is gradually torn down between 1800 and 1860.

- Amsterdam is a city with vast differences in social and economic status. Most inhabitants are unable to regularly pay their rents, and thousands live in cramped cellars, attics, or rookeries, or until the mid-eighteenth century in illegal sheds beyond the city walls.

- The existence of women in the underclasses is even more precarious than that of men. Amsterdam women are known for their independence and assertiveness. Women dominate communities in working class neighbourhoods, especially in harbour districts where the men are often away working on the merchant and maritime fleets. Women also play a prominent part in riots.

- Amsterdam is a noisy city, with lots of traffic. The city government tries (mostly in vain) to create quietness in streets and areas where wealthy citizens live.

- Amsterdam has an extensive sanitation department, and city cleaners collect and dispose of waste from streets and canals. Nevertheless there is stench and nuisance from the poor quality of the water in the canals and from the smoke produced by chimneys from houses and industries.

- Amsterdam is a lively city: much of everyday life is performed in the streets and other public spaces, and in public buildings.

- Amsterdam is not completely dark by night: from 1669 more than 2,000 oil lanterns are installed and operated by private lantern lighters. Gas lighting is not installed until 1847.

- Amsterdam is a Protestant city. After the Protestant take-over of 1578, the Calvinist Gereformeerde kerk becomes the official church, even though less than one in ten of the population is Calvinist. The official churches are public spaces where people can freely enter. Worship in churches from other denominations such as the Lutheran churches of Scandinavian and German migrants, the Jewish synagogues, and even the Catholic ‘underground’ churches, is tolerated as long as it does not threaten public order.

- After the French occupation in 1795 freedom of religion is introduced and in 1796 the Jews are allowed citizenship; however, the Calvinist church (after 1815 called the Nederlandsch-Hervormde) remains dominant. For instance, on Sundays, most entertainment venues in the city are closed.

Economy

- In the first half of the seventeenth century Amsterdam commerce expands dramatically and the city becomes a key hub in the global and European transit trade.

- The Amsterdam financial market and the city’s commercial infrastructure (insurance, banking, solicitors and notaries, the stock exchange, auctions, the judicial system, etc) are adapted to the needs of commerce.

- A wealthy elite of merchants, investors, and public servants control and provide regular work to a middle class of artisans and shopkeepers, and irregular work to the labouring and maritime lower classes.

- Much employment is connected to the shipping and mercantile industries: shipwrights and carpenters, sail- and mast-makers, rope-makers, coopers, dockworkers, and so on.

- Women operate a significant proportion of the public houses, lodgings, and pawnshops. They work as fences, as crimps or recruiters for the VOC, and as prostitutes and procuresses.

- Amsterdam has an extensive system of poor relief that is, however, still too limited to provide for the needs of all its inhabitants.

- After 1650 decline sets in, with a short recovery in the 1680s and 1690s. This negatively affects the demand for consumer goods, including luxuries.

- Trade in colonial goods from the East and West Indies is an exception to this decline and becomes more important, with its volume increasing until the 1730s.

- Amsterdam remains a maritime city, and by the nineteenth century a third of employment is still in some way connected to the maritime trade. The domestic manufacture of luxury goods also thrives, and industrial enterprises are located at the city’s edge (gas factories, sugar refineries, leather and tanning industries, and so on).

Governance

- Down to the French occupation of 1795, Amsterdam is an autonomous city-state. Because of its economic wealth it has a powerful position in the Estates of Holland and, through them, in the Estates-General, the ruling body of the confederation of provinces (such as Holland) that together form the Dutch Republic.

- Amsterdam is ruled by a merchant oligarchy. The burgemeesters (mayors) run the city government and are chosen by sitting and former schepenen (aldermen) and mayors. Aldermen are selected by the Stadtholder of Holland (the Prince of Orange) from a list of candidates nominated by the mayors. In periods when Holland does not have a Stadtholder (1650–1672, and 1702–1747) the aldermen are appointed by the mayors. Aldermen, mayors and the schout (the sheriff in charge of justice and police) are judges and legislators.

- The French occupation of 1795 leads to the takeover of the city by a revolutionary committee and to an elected city government. However, in 1798 the new regime of the Netherlands (or as it is then called the Batavian Republic) ends the autonomy of the cities and directly appoints the city government. Elected councils only return in 1824 in the post-Napoleonic Kingdom of the Netherlands, although voting is limited to those 7,000 males who are above both twenty-five years old and a certain tax threshold.

Colonialism & Slavery

- Amsterdam merchants are key founders of and capital providers for both the Dutch East India Company (the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC, created in 1602 and existing until 1796) and the West India Company (founded initially in 1621, re-founded after bankruptcy in 1674, and dissolved in 1791). These companies are private for-profit enterprises granted monopolies by the Dutch Republic on the trade in Asia (VOC) and the Americas and West Africa (WIC), and to manage Dutch trading posts and colonial possessions.

- The trade in colonial goods, including intoxicants, is of primary economic significance for Amsterdam.

- The use of armed force is essential in gaining access and control over intra-Asian and Asian-European trade, and in establishing plantation economies in the Americas.

- Slavery is essential in providing forced labour for Dutch plantation economies of the West Indies.

- Until the 1730s the WIC has a monopoly on the trade in enslaved persons from West Africa to the Americas.

- The city of Amsterdam is one of the three shareholders in the Society of Suriname that between 1686 and 1795 builds and rules a plantation economy in Suriname (Dutch Guyana) based on slavery.

- Slavery is not abolished by the Kingdom of the Netherlands until 1863.

Further Reading & Resources

- J. E. Abrahamse, ‘De grote uitleg van Amsterdam. Stadsontwikkeling in de zeventiende eeuw’ (PhD thesis, University of Amsterdam, 2010).

- R. Aerts and P. de Rooy (eds), Geschiedenis van Amsterdam, vol. III, 1813–, Hoofdstad in aanbouw (Amsterdam, 2006).

- Amsterdam City Archives

- W. Frijhoff & M. Prak (eds), Geschiedenis van Amsterdam, Vol. II-1, Centrum van de wereld 1578–1650 (Amsterdam, 2004).

- W. Frijhoff & M. Prak (eds), Geschiedenis van Amsterdam, Vol. II-2, Zelfbewuste stadstaat 1650–1813 (Amsterdam, 2005).

- P. J. Knegtmans, Amsterdam. Een geschiedenis (Amsterdam, 2011).

- E. Kuijpers, Migrantenstad. Immigratie en sociale verhoudingen in 17e-eeuws Amsterdam (Hilversum, 2005).

- H. Nusteling, Welvaart en werkgelegenheid in Amsterdam 1540-1860. Een relaas over demografie, economie en sociale politiek van een wereldstad (Amsterdam, 1985).

- M. H. D. van Leeuwen & J. E. Oeppen, ‘Reconstructing the Demographic Regime of Amsterdam, 1681–1920’, Economic and Social History of the Netherlands 5 (1993): 61–102.