What’s Your Poison?

Five free streamed talks, open to all, exploring the history of specific intoxicants. Seminars will take place on Wednesdays at 1–2pm UK time (BST/GMT) – with the exception of the session on Wednesday 29 September, which will be held at 5pm UK time (BST) – over the secure and user-friendly platform Crowdcast.

Wednesday 29 September, 5–6pm BST

Spices

The Hot Stuff: Early Modern Trafficking in Spices

Gitanjali Shahani

This paper looks at a period in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, when English explorers and merchants embarked on a transnational quest for ‘the hot stuff’, setting into motion a long-term intercourse with the Indies. Pepper, cloves, nutmeg, and mace were only some the rare commodities that infiltrated the English marketplace, via the newly formed East India Company. But even as the pungent odours of these condiments wafted into English homes, several writers worried about the implications of consuming the ware of ‘Blackamores’ and ‘Bantamen’. This paper explores the forms in which early modern writers grappled with emergent notions of racial, cultural, and religious alterity in their responses to the spice trade. Analysing plays, pageants, domestic manuals, and receipt collections, the paper takes us through racial incarnations of Indian spices as Indian subjects in the writings of authors like Shakespeare and Middleton.

Wednesday 27 October, 1–2pm BST

Coffee

Clandestine Coffee and a Female Underground Culture in Late Eighteenth-Century Stockholm

Hanna Hodacs & Anna Knutsson

Sweden handled the growing demand for coffee in the long eighteenth century in rather a unique way; attempting to address the negative trade balance, coffee was repeatedly prohibited between 1756 and 1823. Large fines were associated with selling, preparing, or consuming coffee. Police officers, who received a third of the fines collected, started to target grocers, pubs, chophouses, and private kitchens, sniffing and searching for all things coffee-related. What they encountered was an urban underground coffee culture which to a large extent was populated by poor and insubordinate women. Drawing on police records from Stockholm from the 1790s and early 1800s, we will explore how the bans pushed coffee underground, and how it opened up economic opportunities for poor women, but also the extent to which poor women made coffee their drink of choice.

Wednesday 10 November, 1–2pm GMT

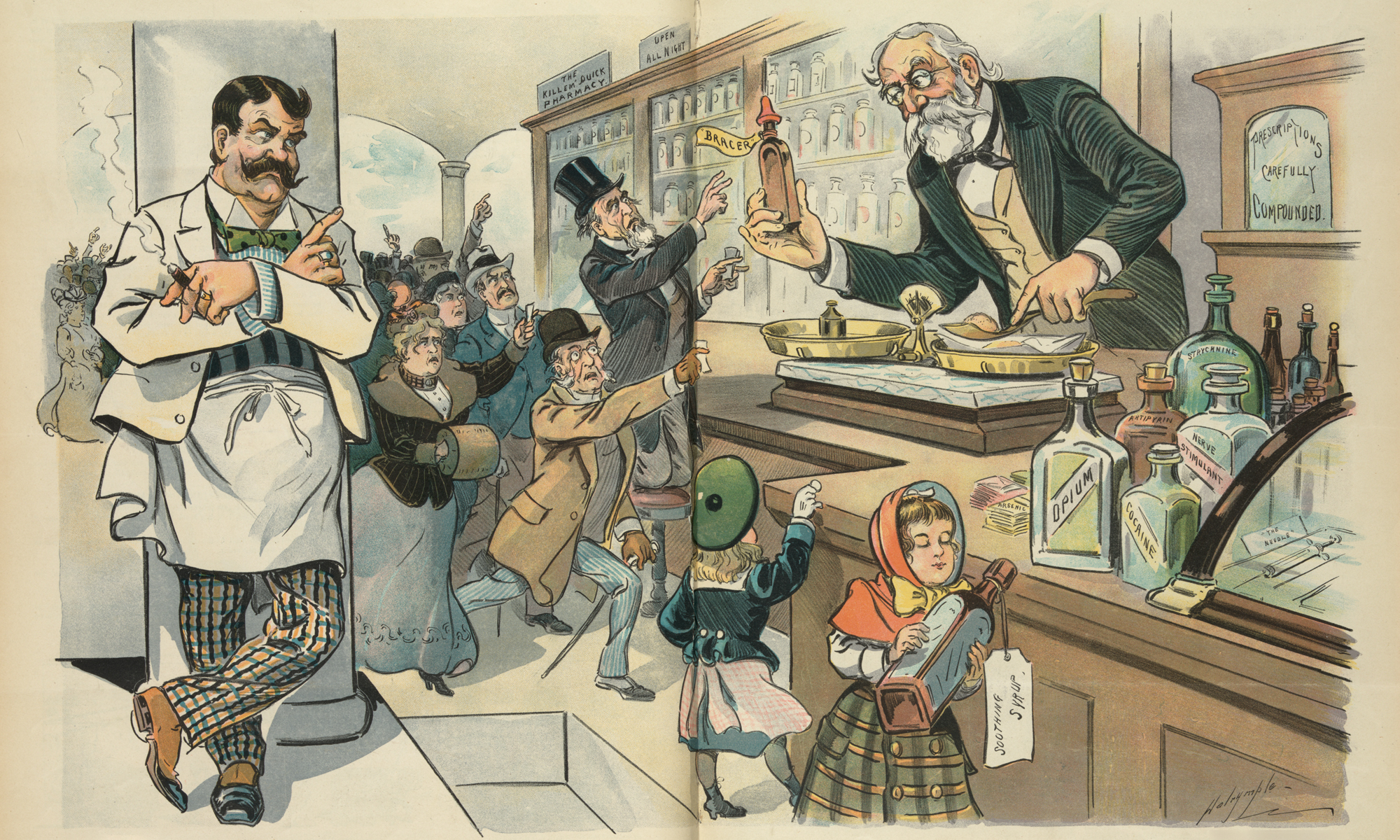

Cocaine

Cocaine Zany: Cocaine in the Sherlock Holmes Stories and Their Parodies

Douglas Small

Sherlock Holmes was described in 1930 as a character who ‘took cocaine before cocaine was fashionable’. The second Holmes novel, The Sign of Four (1890) famously begins with the image of the detective methodically injecting himself with a ‘seven-per-cent solution’ of the drug. This paper examines both the representation of Sherlock Holmes’s cocaine habit in Doyle’s works, and its comic reworking in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. In the Holmes cannon, cocaine is intimately bound up with Sherlock’s single-minded commitment to his work: Holmes appears as a ‘perfect reasoning and observing machine’ who turns to cocaine only ‘as a protest against the monotony of existence when cases [are] scanty’. Parodic works like the 1916 silent film comedy The Mystery of the Leaping Fish, however, reframe Holmes’s unrelenting commitment to work as a continual, hyperactive quest for pleasure, playfully intermingling the apparently disconnected extremes of work-life, and drug-life.

Wednesday 8 December, 1–2pm GMT

Rum

Drink Up Me Hearties: A History of Piracy and Rum

Jamie Goodall

The Caribbean played host to some of the most unsavoury characters in the Atlantic world: pirates. They would attack and loot merchant vessels, often taking the crew hostage and removing valuables for sale in ports across the waters. And pirates were widely known in contemporary sources for their propensity for drunkenness, drinking anything they could get their hands on. And rum was undoubtedly their favourite beverage for long voyages. But why rum? Liquor, and in particular rum, rose to prominence on naval, merchant, and pirate vessels. For example, grog, a well-known mariners drink, was a blend of rum, water, and sometimes lime, mixed with water to sanitise it after stagnation. The vast majority of the world’s rum came from the Caribbean with Jamaica and the surrounding areas producing the most. Sugar was a large and plentiful resource there, which was exported to America and Europe, but which was expensive to move. Rum, distilled from sugar, was cheaper to transport and so became a staple export. This meant that many of the ships attacked by pirates were laden with barrels of rum ripe for the taking. It also meant that, while in port, rum was cheaper to purchase and consume. So how did pirates become associated with drunkenness? The Caribbean spirit came out of the still at 140 proof and was a lot stronger than the beer and wine it replaced. The British Navy rationed grog to sailors twice a day, but pirates could have as much as they desired.

Wednesday 12 January, 1–2pm GMT

Opium

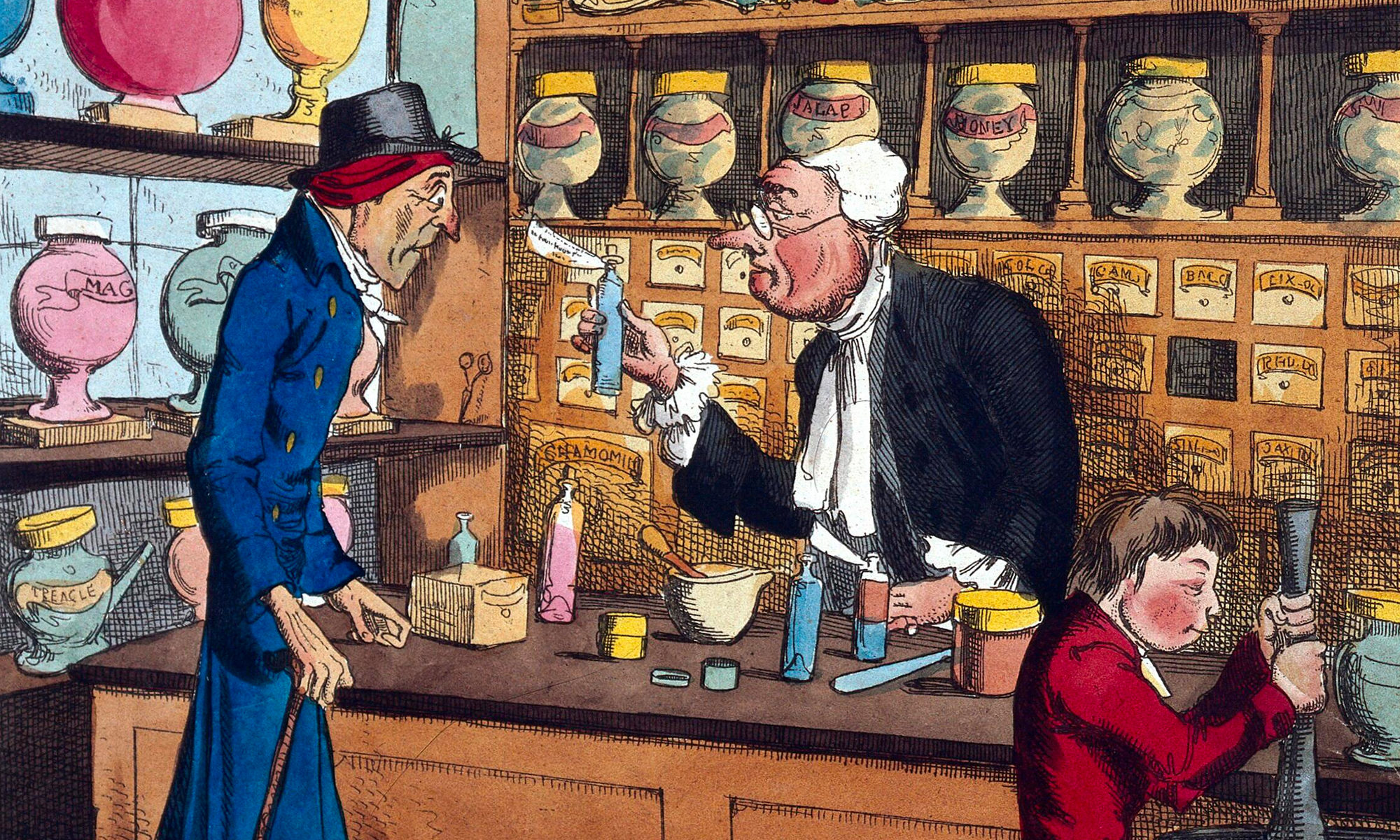

The ‘Magnum Dei Donum of the Materia Medica’: Opiates in Antebellum American Medicine

Jonathan S. Jones

This paper explores the changing place of opiates in antebellum American medical therapeutics and thought. Opiate addiction among ailing veterans was a major medical consequence of Civil War military medicine, a product of widespread opium, morphine, and laudanum usage during the war. But where did these usage patterns originate? This paper traces how, in antebellum medicine, opium transformed from simply one of many useful drugs to the preeminent drug in American physicians’ black bags, setting the stage for the post-Civil War addiction crisis. The paper is a chapter in my longer book manuscript on opiate addiction and Civil War veterans in the nineteenth and early twentieth century United States, currently in progress.

Images via the Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0), British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain), Library of Congress (Public Domain), and Rijksmuseum (CC 1.0 Universal)