A key part of the Intoxicating Spaces project is our work with schools in the UK, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Back in October, a group of 30 pupils from our Stockholm partner school Nacka Gymnasium joined our Swedish research team at Nordiska Museet, Sweden’s largest museum of cultural history, for a day among their intoxicant-related holdings. Here, the pupils share their favourite discoveries…

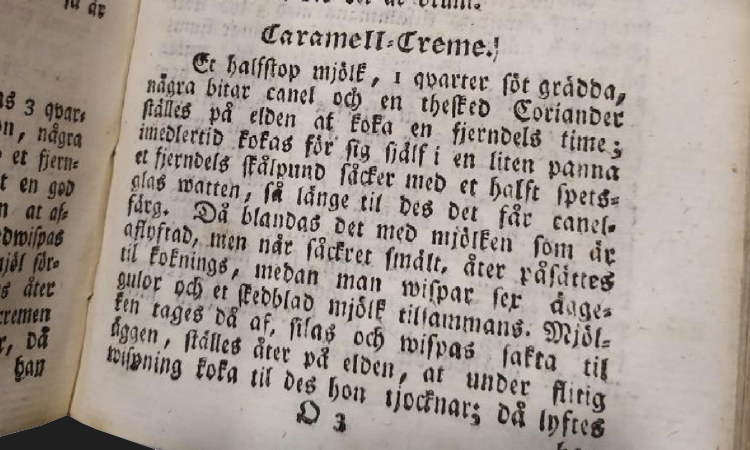

1. A Recipe for ‘Caramell-Creme’

I have examined a recipe for ‘caramell-creme’ in the book En Liten Hushållsbok, written by the upper middle-class woman Anna Maria Rückerschöld in 1785. Rückerschöld wanted to spread her ideas about cooking and housework among Swedish women from this social group. Although the recipe contains a lot of sugar which was expensive, she assumed people could afford expensive products. She was famous for her books and ideas about housework, and thought women should receive education like men, although still wanted to retain traditional gender roles (her aim was to educate women and improve their management of their households with advice books). Anna was influenced by the so-called ‘age of enlightenment’; it was important to be practical, and luxurious details and extravagant practices from the past were no longer relevant. She was also clearly influenced by protectionist, mercantilist ideals regarding being self-sufficient as much as possible; she wanted to encourage the use of Swedish products and Swedish recipes, and regarded the increasing volume of imports with dismay (sugar is therefore the only foreign ingredient). Teodor Arbman

2. A Container for Snuff

This is a Swedish snuff container made out of silver with the initials ‘I. L. S.’ engraved on to the metal. It was made in Karlstad by Niclas Warneck in 1752. The box is clearly one for upper class men given the precious metal and the many man hours put into the object’s construction. Snuff came to Europe in the sixteenth century from the island Hispaniola in Central America. It became a common trend among the important men and women of the French Royal Court; it is said that the French ambassador Jean Nicot advised the queen Catherine de Medici to use snuff in order to cure her chronic headaches. The first time it is mentioned in Sweden is 1637, and by the eighteenth century its use was very common among aristocratic men. The container itself was an important item in the accoutrement of a fancy man. Today, snuff is no longer symbolic of great wealth; it is used by the working as well as the upper classes, but is still associated with males. However, the use of snuff is growing across both genders in Sweden, and a particular trend is for woman to use the powdered, tobacco-less product ‘snus’ in an attempt to stop smoking. These white nicotine pouches will probably replace snuff as they are perceived as more healthy. Teodor Arbman & Karl Ekstrand

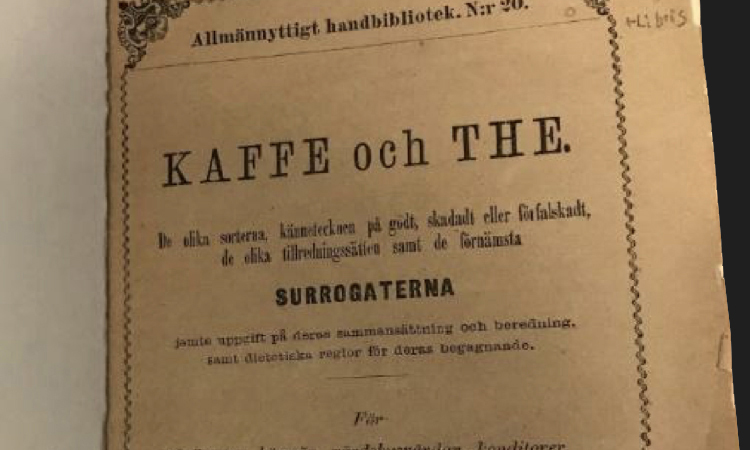

3. Substitutes for Coffee and Tea

This book includes a collection of different types of, and substitutes for, coffee and tea. It was written by the German author Wilhelm Neuhof, and has here been translated into Swedish. It was published in 1823, the same year in which the last of the coffee bans expired. As such, the source tells us much about how people dealt with the ban of coffee, including developing substitutes made out of, for example, juniper berries or blackberry seeds, and how these replacements were made and served. The book could have benefitted Sweden’s economy after the coffee ban was reversed, by informing people of the many different ways to approximate the taste of coffee using ingredients widely available in Sweden (promoting the use of home-grown products over foreign ones, whose import was seen as detrimental to the Swedish economy). Today we continue to use various substitutes of coffee, but not because regular varieties are forbidden; instead, we have them because tastes for coffee have diversified and the market for different styles has grown. Nilo Ek & Nike Brattnäs

4. A Widow’s Tobacco

This painting is called Borgenskapets Enkehus, meaning burgher’s widow’s house, which was a charity where the bereaved wives and daughters of poor burgher’s could live following the their deaths. The painting, composed between 1812 and 1882, depicts a boy delivering a newspaper at the door, a woman drinking medicine, and, to the left, another women enjoying snuff. As Teodor discusses above, snuff was a loose powdered tobacco to be snorted, which arrived in Sweden in 1637, and whose consumption became widespread during the eighteenth century. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was common for snuff to be applied to the gum beneath the upper lip, which is what seems to be happening in the painting. The consumption of continues to be popular in Sweden, although is now unusual in other countries; in the future we believe that the use of tobacco-less snuff will grow and come to replace traditional varieties in Sweden and elsewhere. Sofia Hildebeck & Henry von Gussich

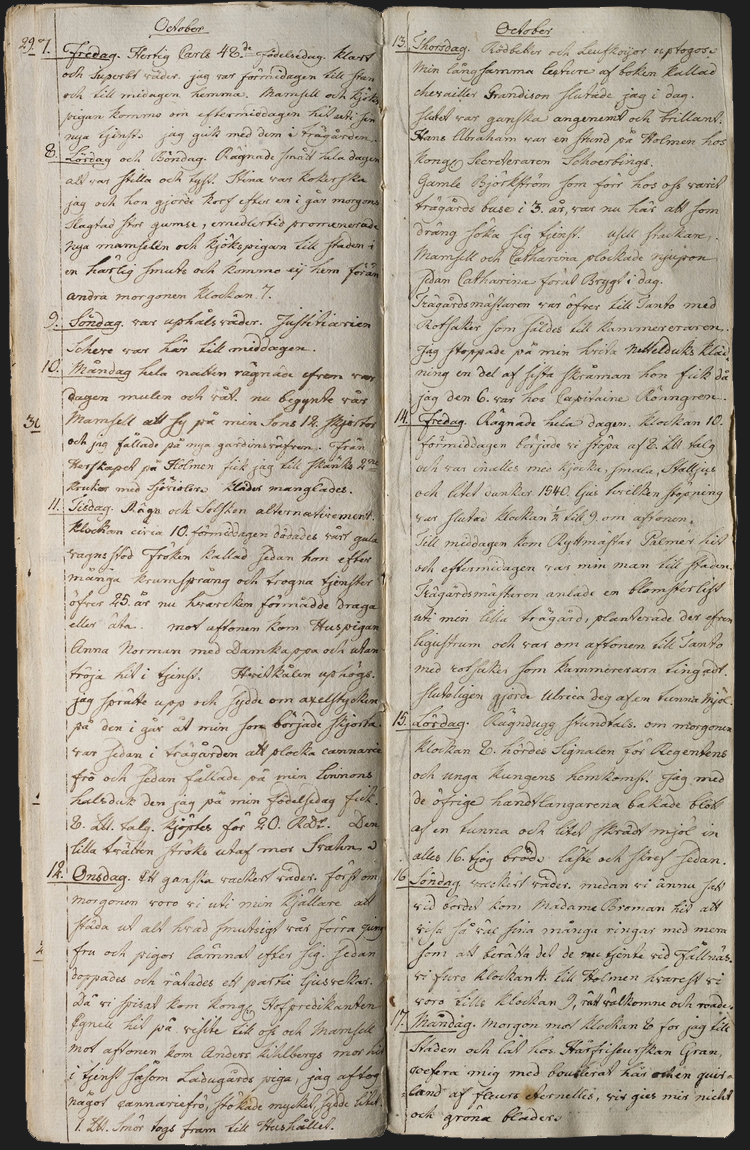

5. Årstafrun’s Diary

Årstadagboken is a collection of diaries written between the 1793 and 1839 by Märta Helena Reenstierna, sometimes known as Årstafrun (the Årsta lady). Born in 1753, Reenstierna lived a wealthy life with her husband, Christian Henrik von Schnell, the love of her life. They had eight children, four girls and four boys, but only one of them survived past the age of eight (a common occurrence at a time when every third child died before the age of one). Märta herself died in 1841, two years after her last diary was written, at 87 years old. Her diary, covering thousands of pages, is divided into three parts, and generally contains realistic, meticulous, and detailed descriptions of life as a peeress in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; it is a real cultural and historical goldmine. They have been used for historical meteorological research since she described the weather every day, although she also wrote extensively about her interactions with various intoxicants. In particular, she loved coffee, and used to drink it regularly with her friends despite its prohibition. Auné Hilding & Amalie Jularbo

6. A Can for Tobacco

This object is a cylindrical cast iron tobacco can from the 1700s. The lid is adorned with an antique female figure, and is also inscribed with the manufacturer’s stamp, HF, which stands for Hellefors bruk. On one side of the jar there are two crowned lions holding a royal crown, an owner’s stamp (G. G. W), and the year of manufacture, which is 1793. On the opposite side there are two two pipe smoking-men and the text ‘ORE FUMOSO BENE BIBTUR’, which loosely translates to ‘it’s good to drink with smoke in the mouth’. Tobacco was first encountered by Europeans as part of their conquest of the Americas in 1492, and was later widely imported and consumed by Europeans for medical and pleasurable use. Today, it mainly takes the form of cigarettes and snuff, meaning that the tobacco-can, used to store leaf tobacco for filling pipes, is no longer useful in day to day life. Indeed, forms and styles of of tobacco usage continue to evolve – as, for example, with the growing popularity of electronic cigarettes – a trend that we think will continue over the coming years. Nicklas Hällsten & Amalie Jularbo

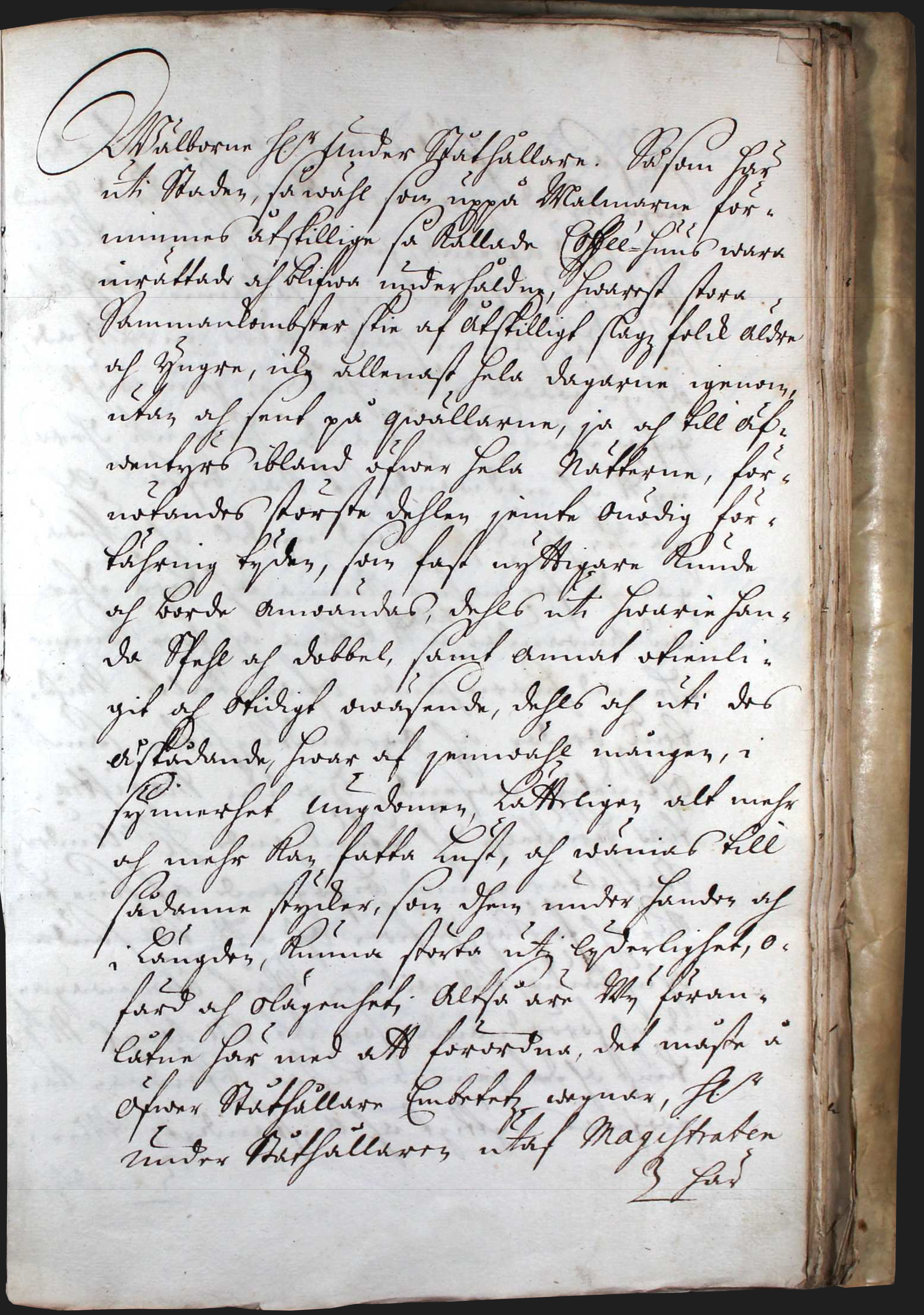

7. A Letter Decrying Coffeehouses

This is a letter written by the Royal Council in the hope of curbing the popularisation of coffee houses throughout Stockholm. It dates to 24 October 1705, by which time coffeehouses had become extremely popular in the city due to their creation of a new way of socialising and connecting different social groups (they were vital cultural and social community places as well as a source of coffee). However, coffeehouses were seen as a problem by the Swedish Royal Council because – according to the Council – disorder, disturbance, and addiction to coffee inevitably followed from their use. This is why they pleaded with the urban authorities to shut them down. However, as elsewhere, royal efforts to curb the proliferation of coffeehouses were unsuccessful, and Stockholm witnessed dramatically increased consumption. Indeed, this is probably why coffee and coffeehouses are so popular in Sweden (the world’s sixth-largest consumer of coffee per capita) today, not to mention the popularity of energy drinks and other consumables which contain caffeine. In the future, so heavily dependent are Swedes on the intoxicant, we might see other forms of caffeine become popularised, for example in the form of pills or other types of beverages. David Madzar

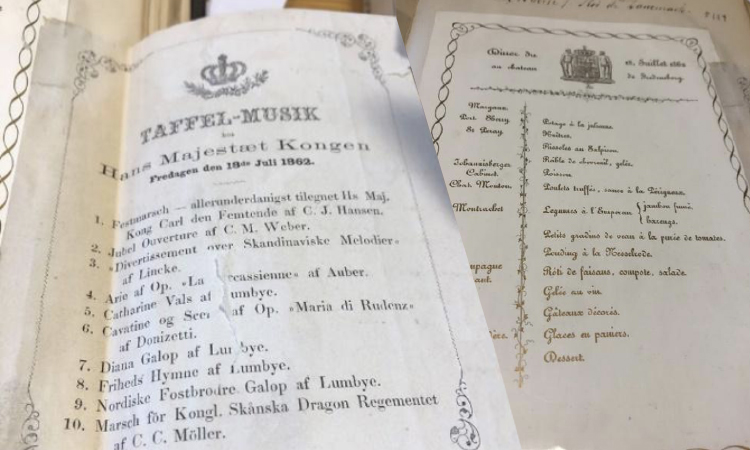

8. A Royal Menu

This is a dinner menu from 1862 prepared for the Swedish king Carl XV, accompanied by musical notation. On the menu you can see new intoxicants such as sugar in the desserts, as well as other lavish items like champagne. The continued exclusiveness of sugar at this point of time is very noticeable. It was used in the homes of somewhat wealthy people as a luxurious item; they generally kept it in a locked box, and cut larger chunks of sugar known as loaves into smaller, more usable bits of sugar for use in recipes or for stirring into tea and coffee. Sugar was expensive and was used sparingly in ordinary homes. But royalty did not hold back. As this menu demonstrates, the amounts of sugar used for a single royal dinner could exceeded the volume a normal household would consume in many months. It was prepared for a state dinner where Danish king Frederick VII was to be entertained; the host likely wanted to show power and his riches by including these luxurious items, probably in unnecessary amounts. Its purpose was to show-off and be ostentatious, not necessarily for taste. In today’s world, by contrast, excessive sugar consumption is often associated with poor health and poverty, and its use will likely decrease in future because of these concerns. Max Westphal, Lukas Totschnig, Henry von Gussich, Mattias Österblad, & Elliot Widholm Lager