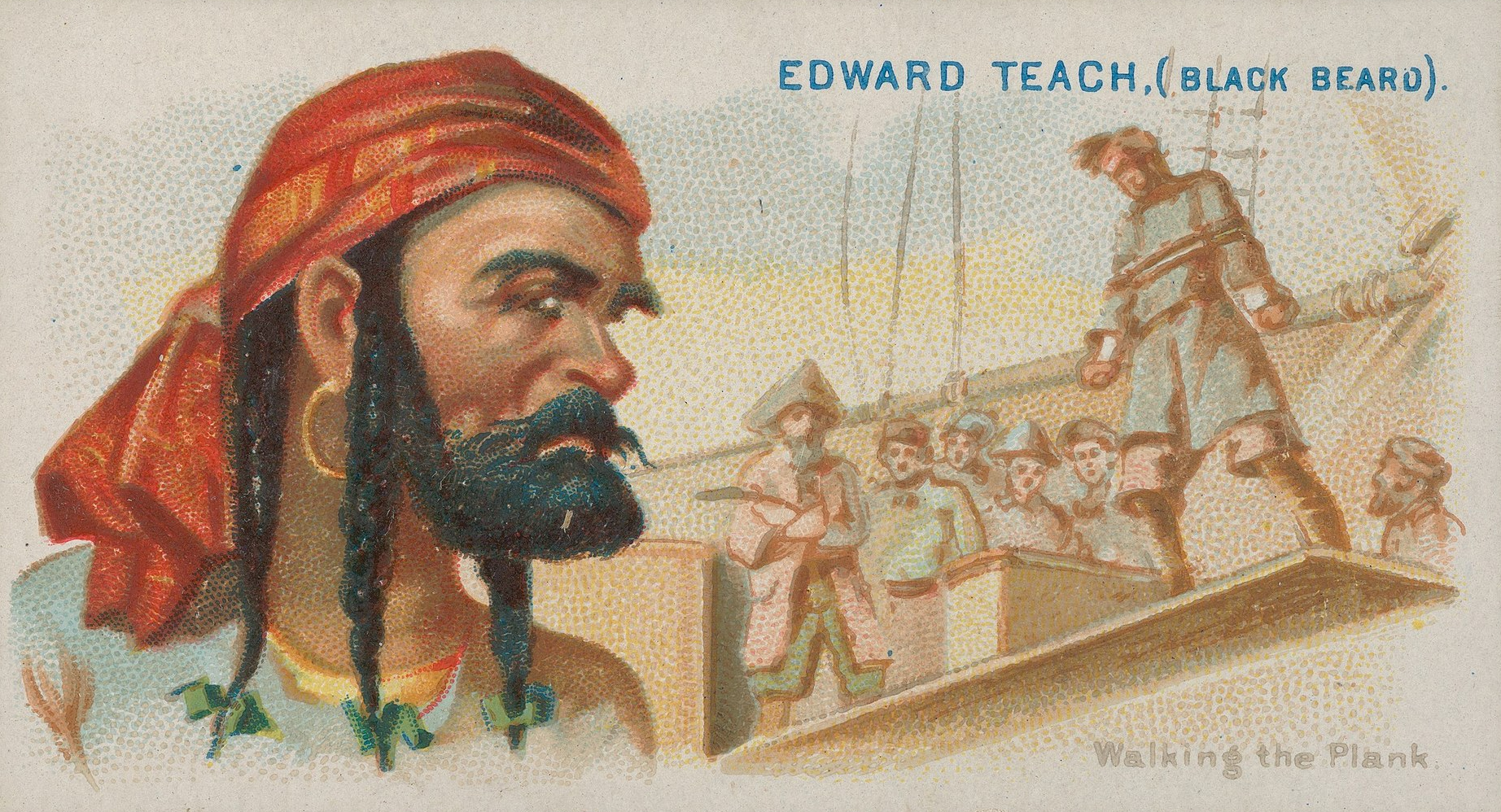

In the 1990s, maritime archaeologists started to excavate the remains of a shipwreck in Beaufort Inlet on the North Carolina coast, excavations that continue (you can follow their progress on this website). It’s now generally accepted that the ship on the bottom of the inlet is the Queen Anne’s Revenge, a frigate with 40 guns and capacity for 150 men that was nothing less than the flagship of a small squadron of pirate ships under the command of one of the most famous pirates in history: Edward Teach, or Thatch, better known as Blackbeard. From letters to the Admiralty, newspaper reports, and testimonies from pirate trials, we know that the ship ran aground on a sandbar on 9 June 1718. Attempts to free her were in vain, and after a few hours the crew abandoned the ship, its valuable cargo, and their personal possessions. Over subsequent weeks the vessel slowly disintegrated and finally ended its eventful life on the seabed.

What makes the Queen Anne’s Revenge interesting for the history of intoxicants? One of the findings in the wreck were seventeen fragments (bowls and stems) of white clay pipes, with the possiblity of many more waiting to be uncovered. These pipes were either of English or Dutch origin, and stood in a long tradition of maritime pipe-smoking. From Columbus onwards, sailors and mariners had been of key importance in the dissemination of tobacco in Western culture. It was, after all, they who first came into contact with the use of tobacco by Native Americans in the New World and took up the habit, introducing it to Europe and from thence to Africa and Asia. Tobacco started its European career as an intoxicant for ‘low-lifes’; upon its introduction in Europe in the sixteenth century the intoxicant was perceived, to quote historian Marcy Norton, as ‘a thing of slaves and tavern drinkers, and people of low consideration’.

At first sailors imitated the Native American habit of rolling the dried and crushed tobacco leaves in a palm leaf, setting it on fire, and smoking it. But the real expansion of tobacco use in the later decades of the sixteenth century was made possible by a technological innovation: the invention of the clay pipe. In consequence, English clay pipes have been regularly found in archaeological excavations of Dutch port towns; in the early seventeenth century English refugees brought pipe-manufacturing techniques to Amsterdam and other cities of the Netherlands, contributing to the normalisation of tobacco within the Dutch Republic. By the 1630s tobacco smoking was widespread throughout all classes of society, and moreover the Dutch developed one of the largest domestic tobacco-growing industries in Europe.

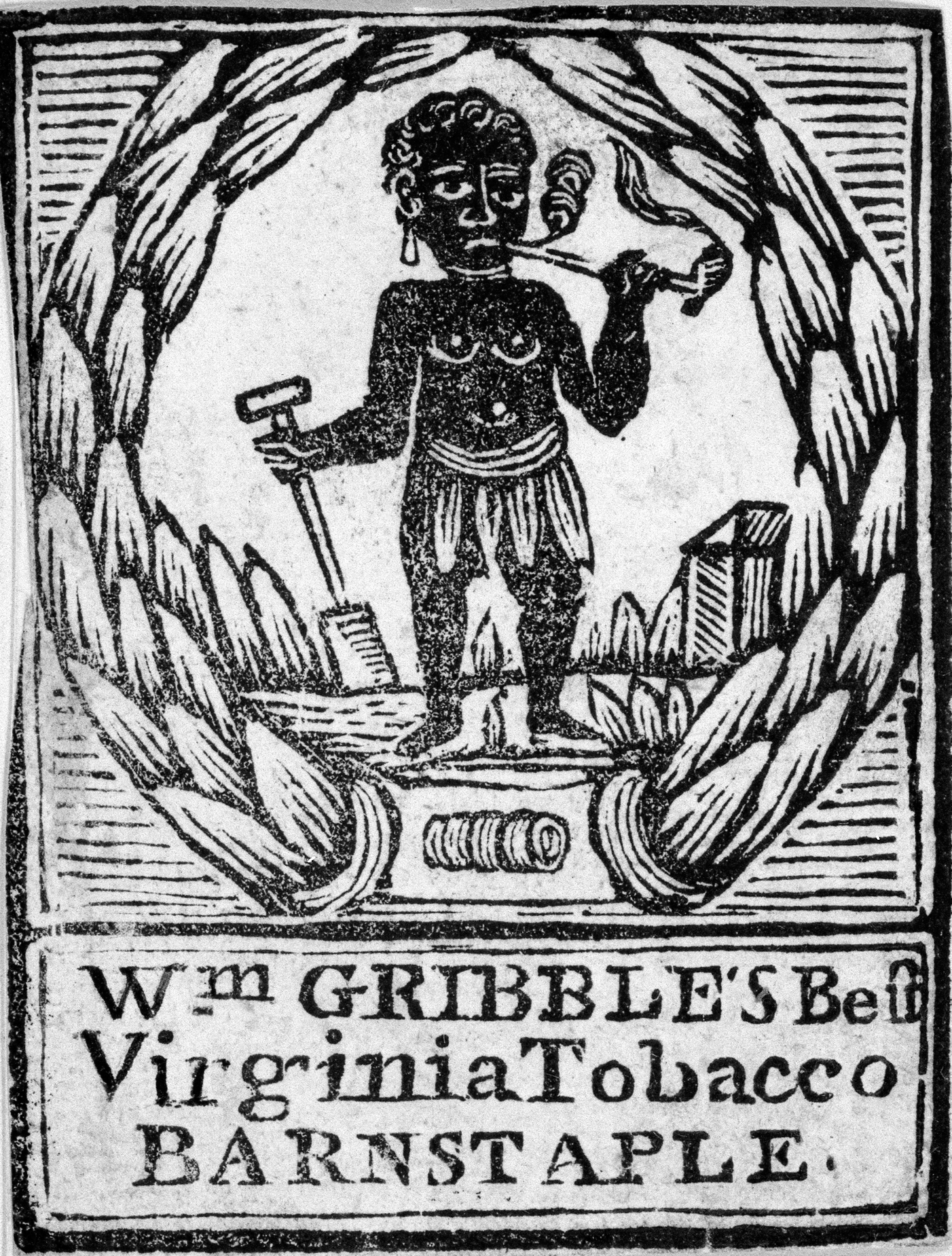

The introduction and assimilation of tobacco within the Netherlands was problematic, however. In the beginning, as in other European countries, tobacco was considered alien and licentious (complaints often articulated in racist language that associated ‘foreign’ smoking with Native Americans and Africans, even as ‘exotic’ images of black people smoking were simultaneously deployed in marketing campaigns and on premises), and in a society dominated by Protestant Calvinism, pleasure and enjoyment itself was suspect and considered by many as sinful. This did not, however, stop mariners from smoking. In shipwrecks of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) archaeologists have found tobacco boxes, while documentary evidence shows that the sailors of the VOC took considerable amounts of tobacco with them to Asia. For instance, at the start of his lengthy voyage in 1752 Georg Naparra packed no less than thirty Amsterdam pounds or 26 kilos of kardoezentabak (tobacco packed in paper) and twelve dozen clay pipes from Gouda (the main centre of the pipe industry) in his sea chest. He was clearly planning to indulge his habit on his way to, and probably also in, the East.

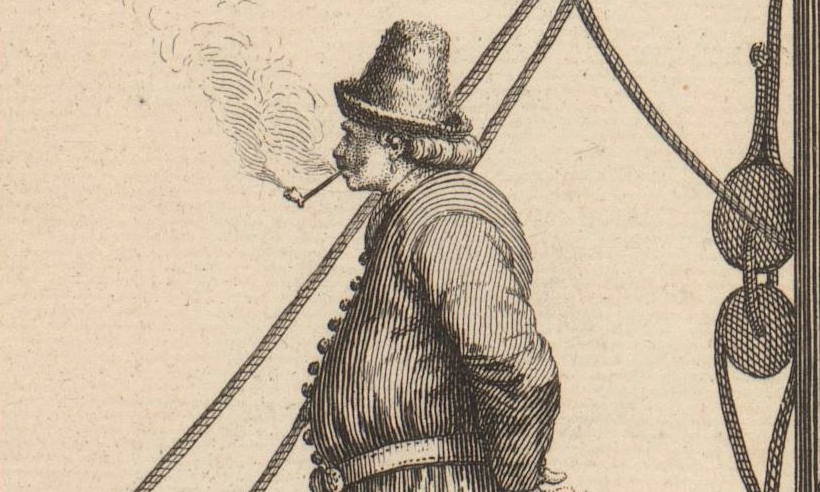

Tobacco smoking was closely regulated on board ships, less because of health issues as because of fire hazards. The earliest Dutch maritime tobacco regulation, from a fleet of privateers in the Caribbean, dates from 1627, and specifies that the sailors could only smoke on the wooden railing before the main mast (the so-called boevenet or ‘villains net’), where in daytime a burning fuse was hung. On a first violation of this regulation the hapless smoker was placed in irons for eight days and formally reprimanded. If he broke the regulations again he was hung from the yardarm and then flogged, in addition to losing a month’s wages. At night smoking was completely forbidden and the sentences were doubled. By comparison, getting drunk was punishable with 14 days on bread and water.

The existence of regulations and punishments suggests the widespread presence of the practices that needed to be regulated and punished. The type of pipe was also important, with mariners tending to use specific varieties. According to the Dutch pipe collector and historian D. H. Duco:

The seventeenth-century pipe smoker was very careful about the choice of his pipe. Comparison of finds from the various areas of Amsterdam showed clearly that each social group chose its own particular kind of pipe. The upper classes, especially those who lived along the Amsterdam canals, usually smoked good-quality, nice, burnished pipes with heel marks. The finishing of these pipes was perfect. By contrast, of the pipes found in Kattenburg, Wittenburg and other sailors’ districts many are unmarked or decorated with the side-mark rose with the dot-shaped leaves. Unmarked pipes were almost never burnished and the side-marked pipes could not be polished because of their relief decoration.

Specific types of pipes, then, were associated with specific social groups, as well as with the challenging of these differences in acts of social and criminal deviance. In a 1681 account of Amsterdam brothels, pipe-smoking appears in two places: among boatmen and sailors who patronised a lower-class brothel in a maritime district; and among the bouncers in a higher-class brothel who are described as having tobacco pipes in their mouths.

It would therefore be interesting to reconstruct the pipes of the pirates. But were they their pipes? There is another explanation of the finding. The Queen Anne’s Revenge had been a French slave ship before its capture by Blackbeard, who possibly even recruited some of the slaves for his crew. It was quite common practice among slavers – attested, for instance, by the regulations of Dutch trading companies – to force the enslaved to smoke tobacco on deck. In addition to other forced activities such as dancing and making music, this was meant as a preventive health measure, to ‘comfort’ the enslaved and to keep them and their resistance to disease at premium level. Apart from its associations with mariners and deviance, then, pipe-smoking also sustained an exploitative economic order in more ways than one.

The findings of clay pipe fragments in the wreck of the Queen Anne’s Revenge may only have meant that pirates liked to smoke. But they also open up new worlds of intoxicant use to those searching for historical treasure…

Further Reading

- K. G. Brooks, ‘Inhaling the Alien: Race and Tobacco in Early Modern England’, in B. Sebek & S. Deng (eds), Global Traffic: Discourses and Practices of Trade in English Literature and Culture from 1550 to 1700 (New York & Basingstoke, 2008), pp. 157–78.

- D. H. Duco, ‘The Clay Tobacco Pipe in Seventeenth Century Netherlands’, in Peter Davey (ed.), The Archaeology of the Clay Tobacco Pipe: Vol. 5, Europe 2 (British Archaeological Reports 106 [ii], Oxford, 1981), pp. 368–468.

- I. Gaskell, ‘Tobacco, Social Deviance and Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century’, in H. Bock & T. W. Gaehtgens (eds), Holländische Genremalerei im 17. Jahrhundert (Berlin, 1987), pp. 117–57.

- R. van Gelder, Naporra’s omweg. Het leven van een VOC-matroos (1731–1793) (Amsterdam, 2003).

- J. Goodman, Tobacco in History: The Cultures of Dependence (London, 1993).

- M. Norton, Sacred Gifts, Profane Pleasures: A History of Tobacco and Chocolate in the Atlantic World (Ithaca, 2008).

- S. Stephen, Vrijbuiters van de heelkunde. Op zoek naar medische kennis in de tropen 1600–1800 (Amsterdam, 2012).

- S. Snelders, The Devil’s Anarchy: The Sea Robberies of the Most Famous Pirate Claes G. Compaen, and Very Remarkable Travels of Jan Erasmus Reyning (2nd ed., Brooklyn, 2014).

- M. U. Wilde-Ramsing & L. F. Carnes-McNaughton, Blackbeard’s Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne’s Revenge (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018).